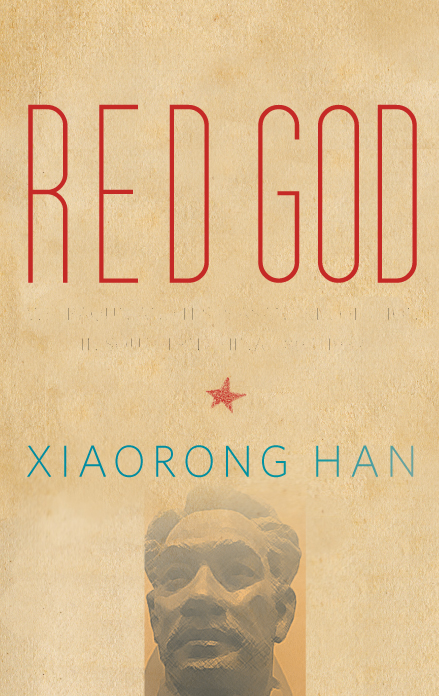

RED GOD

SUNY series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture

Roger T. Ames, editor

RED GOD

Wei Baqun and His Peasant Revolution

in Southern China, 18941932

XIAORONG HAN

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2014 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production by Eileen Nizer

Marketing by Michael Campochiaro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Han, Xiaorong,

Red God : Wei Baqun and his peasant revolution in southern China, 18941932 / Xiaorong Han.

p. cm. (SUNY series in Chinese philosophy and culture)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4384-5383-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4384-5385-9 (ebook)

1. Wei, Baqun, 1894-1931. 2. CommunistsChinaBiography. 3. Peasant uprisingsChinaGuangxi Zhuangzu ZizhiquHistory20th century. I. Title. II. Title: Wei Baqun and his peasant revolution in southern China, 18941932.

DS777.488.W48H36 2014

951.4'1092dc23

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To Ah Meng and Bo Ning

Contents

Illustrations

Maps

Figures

Acknowledgments

It would have been impossible for me to complete this project without the assistance of the many teachers, colleagues, friends, and relatives who made my protracted search for the meanings of Wei Baquns life and revolution a pleasant and fruitful learning experience.

In Nanning, Fan Honggui and Chen Xinde were very generous in sharing both source materials and insights with me. So did Ya Yuanbo in Hechi. In Baise, the Municipal Office of the CCP History and the Municipal Archives both opened their doors to me and Wei Yongmei was particularly helpful. The Baise Uprising Memorial Hall granted me the right to use the image of a statue of Wei Baqun in this book. In Donglan, the four researchers at the Office of the CCP History, Huang Haoye, Shi Jietai, Wang Honghua, and Wei Hui twice received me and offered me numerous books they had written and edited. Wang Hao of the Political Consultative Conference of Donglan provided some very useful and hard to find locally published books and journals.

Wu Yixiong of Sun Yat-sen University and Pan Jiao of Minzu University granted me valuable opportunitiues to present my research to their colleagues and their very bright students.

Stephen Uhalley Jr., Paul Hansen, Bruce Bigelow, and Li Huaiyin all read the entire manuscript and David Mason read the first two chapters. They all provided very helpful suggestions. I also benefited from conversations with the late Jerry Bentley, Richard L. Davis, Edward Shultz, Huang Xingqiu, and Huang Ying, as well as various forms of assistance from Monte Broaded, Antonio Menendez, Bob Holm, and Scott Swanson.

Susan Berger of the Irwin Library of Butler University was very efficient in acquiring a large number of books and articles I requested through the interlibrary loan service. Matthew Jager of the Butler University Writers Studio provided editorial assistance for the first draft of the manuscript.

The two grants I received in 2010 from the Butler University Institute for Research and Scholarship and the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange, which were for another project, enabled me to travel to Guangxi and other places to pursue my sideline research for this book.

The two anonymous reviewers for the SUNY Press provided very enlightened and constructive general comments and specific suggestions. Roger Ames and Nancy Ellegate were as helpful this time as they were in the publication of my first book. Eileen Nizer, Jessica Kirschner, Ryan Morris, and Michael Campochiaro were very prompt and patient in offering guidance and assistance with regard to the production of the book.

My former teachers, the late Wu Wenhua in Xiamen, Li Yifu in Beijing, Daniel Kwok, and Truong Buu Lam in Hawaii, were always ready to enrich me with their wise advice and enliven me with their kind encouragement.

Within my family, my wife Liu Meng read both the first and the final draft and made numerous corrections; my brother Yongqing helped purchase a number of very useful old books; and my son Bo Ning read part of the manuscript and also served as a first-class technical assistant.

I am profoundly grateful to all the people and institutions mentioned above as well as to many whose names do not appear here.

Introduction

It was sometime before dawn on October 19, 1932.

Wei Ang, a stout young man, was sitting by a fire at the bottom of the Fragrant Tea Cave (Xiangchadong) on the slope of one of endless mountains in the Western Mountains (Xishan) region of Donglan County, Guangxi Province in southern China. The flickering firelight from time to time lit the pockmarks on Wei Angs face, a legacy of the smallpox epidemic. Near Wei Angs feet lay his mother, his second wife, and his younger sister. The four had fled to the cave when the Nationalist troops stormed their village to enforce their most recent military campaign against the Communists. Wei Ang took the cave as a safe haven because its entrance was far away from the nearest road and also hidden behind trees and grasses. The cave was about three meters deep and had a rather narrow bottom. On its innermost wall, a few steps above the bottom, he had found a hollow space large enough to make a small resting place. In that cave within the cave lay a bed made of three pieces of planks and in it were two men in deep sleep. It was quite cold in the cave and both men covered themselves with thick blankets.

Wei Ang had gone through a sleepless night, partly because he had to stand guard over the two men in the bed, and partly because he had a difficult decision to make. One of the two men was his uncle, none other than Wei Baqun, a member of the Central Executive Committee of the Chinese Soviet Republic, the Communist state based in Jiangxi and headed by Mao Zedong. In addition to that symbolic position, Wei Baqun was commander-in-chief of the Right River Independent Division of the Chinese Workers and Peasants Red Army as well as one of the most important leaders of the Right River Revolutionary Base Area. In addition to these official titles, since 1921 he had been known as the supreme leader of the Donglan peasant movement, and the most well-known revolutionary in the Right River region as well as in Guangxi Province. For the last two nights, Wei Baqun and his bodyguard Luo Rikuai had camped out with Wei Angs family, but the two were planning to slip away for neighboring Guizhou Province the next morning to escape from their Nationalist pursuers.

Because Wei Ang lost his father at an early age, Uncle Baqun had been like his father, providing food for him, helping him find a wife, and also bringing him into the revolution and appointing him to various positions. At one time he was even made to serve as Uncle Baquns bodyguard. The revolution had already changed Wei Angs status to the extent that this formerly poor peasant had even been able to find himself a second wife, a privilege enjoyed only by the wealthy and powerful, and Wei Ang had expected further changes. Unfortunately, the revolution that Uncle Baqun had launched, which had once been so robust and promising, was now on the brink of collapse. The entire Right River Independent Division had been dispersed, the leaders of the revolution were hiding in caves or had moved to other areas, much of the revolutionary base area had been lost, and the center of the base area had been besieged by Nationalist troops. Wei Ang believed that the revolution was almost over and there would be no hope for Uncle Baqun to rise again. If Wei Ang had been grateful to his uncle for the beneficial changes in his life when the revolution was strong and energetic, he was now somewhat resentful for the difficulties that he believed Uncle Baqun had caused. He thought that continuing the failing revolution would bring about not just inconveniences, but also many deaths. Quite a few of Wei Baquns relatives had already been killed, and Wei Ang did not want to be the next to die.