Cress Donald A. - On the Social Contract

Here you can read online Cress Donald A. - On the Social Contract full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Indianapolis;Cambridge, year: 2019;2018, publisher: Hackett Publishing Company, Incorporated, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:On the Social Contract

- Author:

- Publisher:Hackett Publishing Company, Incorporated

- Genre:

- Year:2019;2018

- City:Indianapolis;Cambridge

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

On the Social Contract: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "On the Social Contract" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

On the Social Contract — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "On the Social Contract" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

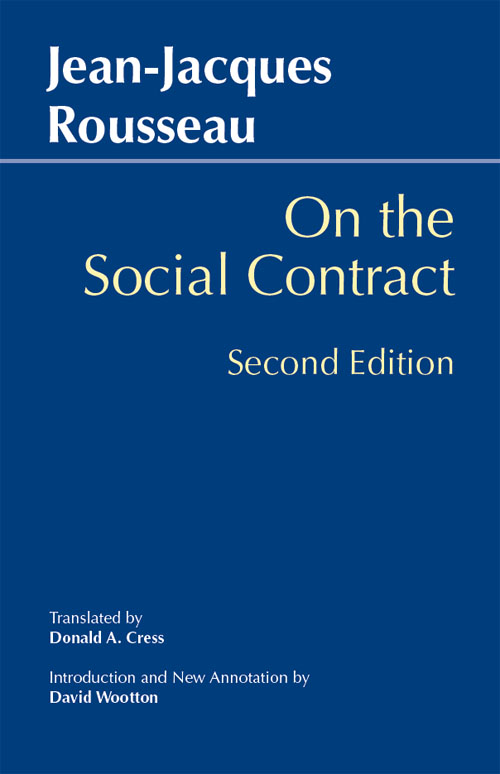

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

On the Social Contract

Second Edition

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

On the Social Contract

Second Edition

Translated by Donald A. Cress

Introduction and New Annotation by David Wootton

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

Indianapolis/Cambridge

Copyright 2019 by Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

For further information, please address

Hackett Publishing Company, Inc.

P.O. Box 44937

Indianapolis, Indiana 46244-0937

www.hackettpublishing.com

Cover design by Listenberger Design & Associates

Interior design by Elizabeth L. Wilson

Composition by Aptara, Inc.

Cataloging-in-Publication data can be accessed via the Library of Congress Online Catalog.

ISBN-13: 978-1-62466-785-5 (pbk.)

ePub3 ISBN: 978-1-62466-803-6

Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince . Translated, with Introduction, by David Wootton.

Niccolo Machiavelli, Selected Political Writings . Edited and Translated by David Wootton.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, The Basic Political Writings , Second Edition. Translated and Edited by Donald A. Cress. Introduction and Annotation by David Wootton.

Voltaire, Candide . Translated, with Introduction and Notes, by David Wootton.

{v} Contents

The page numbers in curly braces {} correspond to the print edition of this title.

{vii}

We are approaching the state of crisis and the century of revolutions.

The tutor in Rousseaus novel mile (1762)

Citizen of Geneva

Jean-Jacques Rousseau was by birth a citizen of Geneva. pupil-clerk with a notary but was dismissed for stupidity. Just before he turned thirteen, he was apprenticed to an engraver. His master beat him; he responded by stealing, and his master beat him all the harder. When he was fifteen, Jean-Jacques went out of the city one Sunday on a jaunt. The city gates were closed a little early, and he and his friends found themselves locked out. Rather than return with his friends the next day for the inevitable beating, Jean-Jacques set out into the unknown. He was homeless, penniless, and friendless. He was to spend the rest of his life looking for a home, but he was incapable of finding one. Nothing could adequately correspond to his imaginary ideal, the home he would have had if his mother had lived.

Rousseau escaped from his immediate predicament by converting to Catholicism. Geneva, the city of John Calvin, was Protestant; converts were welcomed and protected by the authorities of the neighboring Catholic states. By converting, Jean-Jacques automatically forfeited his citizenship; he was no longer a citizen of Geneva. He was sent (on foot, 150 miles through the {viii} mountains) to Turin, where, after being instructed in his new faith, he found employment as a lackeya menial servant wearing his employers uniform. His first employer died, and when her possessions were being inventoried, it turned out a little silver ribbon was missing. Jean-Jacques had stolen it, but he accused an innocent serving girl. Both were dismissed, and for the rest of his life Rousseau was tormented by the thought that Marion, without a reference, faced a future of prostitution, destitution, and early death. Jean-Jacques was more fortunate: he found new employment and was soon being groomed for promotion. But the prospect of spending the rest of his life as a servant was intolerable to him and, after eighteen months in Turin, he set out back toward Geneva. Rousseau had experienced dependence, and for the rest of his life he clung desperately to independence. He had waited on the rich, and he had learned to hate them. Later he would write, I hate the great; I hate their high status, their harshness, their pettiness, and all their vices, and I would hate them even more if I despised them less.

Jean-Jacques returned, not to Geneva but to Annecy, thirty miles south of Geneva. There, when he first fled Geneva, he had been taken in by Franoise-Louise de Warens, herself a convert from Protestantism who was paid a pension to encourage others to convert. Mme de Warens, who was separated from her husband, was thirteen years older than Jean-Jacques, and he quickly fell in love with her. For a few years, he was unsettled: he spent a year wandering, spending time in Lausanne and Neuchtel and pretending to be a music teacher, a job for which he was hopelessly ill equipped. He walked three hundred miles to Paris and briefly worked as a tutor. He walked back to be reunited with Mme de Warens, now in and Mme de Warens always insisted that she was incapable of erotic feelings (although she had lovers besides Rousseau). Rousseau, who had received no formal education, now had the run of an excellent library and little else but reading to occupy his time.

After six years, he found himself supplanted in Mme de Warens affections, and two years later he left to become a tutor, first in Lyons, then in Paris. For eighteen months, he was secretary to the French ambassador {ix} to Venice but was dismissed for insolence. At the age of thirty-three, he returned to Paris, and there he tried to make a living writing music. He also became a research assistant to a wealthy couple, the Dupins. Louise-Marie-Madelaine was writing an endless feminist tract, and Claude was soon writing a vast, unreadable refutation of Montesquieu. Rousseau also fell in with Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond dAlembert, who were embarking on an ambitious and subversive enterprise, the great Encyclopdie , a compendium of progressive thinking. Out of friendship, they commissioned him to write articles on music. Meanwhile he had taken up with Thrse Levasseur, a laundress. She was not officially either his mistress or his wife (visitors mistook her for his housekeeper), but their relationship was to last until his death, and they were to have five childreneach of whom was taken promptly to the Foundling Hospital and abandoned. This was not particularly uncommon (Rousseau himself noted statistics suggesting 25 percent of children born in Paris were abandoned), but the death rate for infants handed in at the Foundling Hospital was very close to 100 percent. Rousseau long kept his abandoned children a secret, and when news of them spread it tarnished his reputation, which has never recovered.

In the summer of 1749, Rousseau was thirty-seven. He was living hand to mouth, with no security; he was one of five hundred or so writers (and perhaps a similar number of musicians) living in Paris, hoping to find some sort of success. He tells us that a whole system of ideas immediately {x} became apparent to himand close reading of the Discourse he proceeded to write suggests this is true. The Discourse on the Sciences and the Arts , which is an attack on progress, prosperity, and sophisticated civilization, not only won the prize; when published, it immediately made Rousseau famousit was even promptly translated into English. Although in the next few years he wrote an opera and a play, he had now embarked on a career as an author, writing several defenses of the First Discourse.

In 1754 he wrote the Second Discourse, On the Origin of Inequality . Again, his target was contemporary French society. This time, before publication, he made a pilgrimage to Geneva, where he rejoined the Protestant church and became a citizen once again. Publication of the Second Discourse in 1755 was followed rapidly by publication of volume five of Diderot and dAlemberts Encyclopdie , which included Rousseaus article on political economy or, rather we might say (for his subject is not economics but the administration of the state), on government. It was at this point that Rousseau adopted (or rather adapted) the idea of the general will, which is at the heart of On the Social Contract . The next year Rousseau left Paris to take up residence on the country estate of a friend, ten miles north of Paris, in a cottage named the Hermitage. From here he published in 1758 a Letter to dAlembert on the Theater , which represented a sustained attack on the views held by Diderot, dAlembert, and their associateswho had been, up to now, his good friends. The ostensible issue was whether Geneva was right to have a ban on theaters, and Rousseau was once again defending ancient virtue against modern sophistication.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «On the Social Contract»

Look at similar books to On the Social Contract. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book On the Social Contract and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.