WHO OWNS

ANTIQUITY?

James Cuno

With a new afterword by the author

WHO OWNS

ANTIQUITY?

MUSEUMS AND THE BATTLE OVER OUR ANCIENT HERITAGE

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2008 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Fourth printing, and first paperback printing, with a new afterword

by the author, 2011

Paperback ISBN: 978-0-691-14810-6

Cloth ISBN: 978-0-691-13712-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2008922048

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion with display font in Bernhard Fashion

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in the United States of America

5 7 9 10 8 6 4

For Sarah, Claire, and Kate

Nationalism becomes self-reproducing in a world of nation-states. For once the world has defined normality as national solidarity and national statehood, every nation must be vigilant against signs of cultural assimilation and must produce nationalists whose self-appointed task is to strengthen national identity and uniqueness in order to increase social cohesion and solidarity. In a world of nation-states, nationalism can never be ultimately satisfied.

Anthony D. S. Smith, Nationalism in the Twentieth Century (1979)

Economic integration, and with it cultural globalization, has far outpaced our global mindset, which is still rooted in nationalist terms. We benefit from all that the world has to offer, but we think only in narrow terms of protecting the land and people within our national bordersthe borders that have been established only in the modern era. The barbed wire, chain-link fences, security forces, and immigration and customs agents that separate us from the rest of the world... cannot change the fact that we are bound together through the invisible filament of history.

Nayan Chanda, Bound Together: How Traders, Preachers, Adventurers, and Warriors Shaped Globalization (2007)

CONTENTS

PREFACE

It is the magic of nationalism to turn chance into destiny.

Benedict Anderson

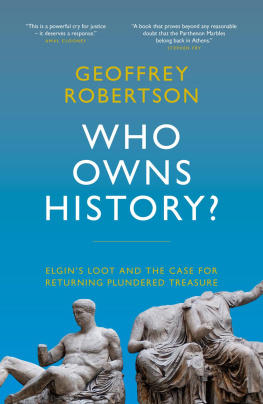

I. Through the first decade of the nineteenth century, Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, British ambassador to the Ottoman court in Constantinople from 1799 to 1803, had numerous sculptures removed from the Parthenon in Athens and shipped to London. He did so, we are told, with permission from the governing Ottoman authorities. The original legal instrument has disappeared and is said to exist only in an Italian translation made for Elgin by the Ottoman court. Some then and now question the legality of Elgins actions. The Italian language document gives Elgin the right to draw, measure, and make plaster casts of the sculptures, and dig for others that might have been buried. It also allows for some pieces of stone with old inscriptions and figures to be taken away. Did this refer to the sculptures on the building or only the fragments found on the ground? The document is not clear. And without greater clarity (and, at this point, probably even with it), no legal case can be made against Britains ownership of the marbles. Still, the modern government of Greece has consistently called for their return.

Whatever the legal circumstances of Elgins actions, they could hardly have been surreptitious. The sculptures, both freestanding and in relief, were numerous and heavy and had to be taken off the building and down from the temples considerable height. They then had to be transported to ships, where, for fear of sinking the ships themselves, Elgins agents sawed off the backs of the thickest relief slabs before loading them. They then sailed slowly away from the coast of the then Ottoman territory, out to sea, and for weeks toward Britain. Considerably impoverished as a result, Elgin offered to sell the sculptures to the British nation. A Select Committee of the House of Commons received testimony from leading British artists as to the sculptures quality, importance, and value. Pronounced worthy of acquisition in 1817, the Elgin Marbles, as they were called, were placed on public display in Montagu House. Thirty-five years later, they were transferred to their first permanent gallery in the new, Robert Smirkedesigned British Museum.

Byron famously criticized their acquisition by the British government, including in verse: Cold is the heart, fair Greece! That looks on thee,/ Nor feels as lovers oer the dust they lovd;/ Dull is the eye that will not weep to see/ Thy walls defacd, thy mouldering shrines removd/ By British hands... Keats wrote positively of them in a sonnet, On Seeing the Elgin Marbles. And Goethe celebrated their acquisition as the beginning of a new age for Great Art. In the meantime, what remained of the Parthenonwhich was much depleted not only from Elgins actions, but also from years of damage, architectural accretions, vandalism, and, most dramatically, the destruction of much of the building in 1687 when Venetian forces of a Christian Holy League formed against the Ottomans bombarded the building with more than seven hundred cannonballs, ultimately igniting the ammunition stored there in a vast explosion that killed as many as three hundred peoplebecame an emotional symbol of a newly independent Greece.

A first attempt at an independent Greek government failed when its president was assassinated in 1831. Two years later, after independence was finally achieved with help from international forces, a monarchy was established with the seventeen-year-old son of King Ludwig of Bavaria on the now Greek throne. Plans were drawn up to rebuild Athens as the new states national capital. Maximilian, the kings brother, commissioned the Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel, who had never been to Athens, to design a royal palace for the Acropolis. But for reasons in part of cost, security, and lack of water supply, the plan was never completed. Another, perhaps more influential reason was that Schinkels rival, Leo von Klenze, the king of Bavarias favorite architect, was convinced that the entire hill of the Acropolis should become an archaeological zone. And so it did, on August 28, 1834.

Klenze oversaw the lavish ceremony marking the occasion. The young German prince (now Greek king) rode up to the Acropolis on horseback. There he was met by young girls dressed in white, carrying myrtle branches. As a band played, he took his place on a throne within the Parthenon and in front of soldiers and courtiers listened to a speech delivered by Klenze in German. Your majesty stepped today, Klenze thundered, after so many centuries of barbarism, for the first time on this celebrated Acropolis, proceeding on the road of civilization and glory, on the road passed by the likes of Themistocles, Aristeides, Cimon, and Pericles, and this is and should be in the eyes of your people the symbol of your glorious reign.... All the remains of barbarity will be removed, here as in all of Greece, and the remains of the glorious past will be brought in new light, as the solid foundation of a glorious present and future. The material remains of the years when the Parthenon served as a Byzantine church and an Ottoman garrison, complete with a small mosque, were removed. The Acropolis became the political symbol of the new Greece. As one archaeologist put it, speaking at a meeting of the newly formed Archaeological Society of Athens in 1838, it is to these stones [the sculpture and architecture of classical Greece] that we owe our political renaissance. Or, as another archaeologist wrote more than a century later, in 1983, the Parthenon is the most sacred monument of this country... which expresses the essence of the Greek spirit.