You Verres will plead that your statues and pictures have adorned the city and the forum of the people of Rome a decoration splendid to the eye, but painful and melancholy to the heart and mind: I looked at the brilliant show that was made by your thefts, by the robbing of our provinces, by the spoliation of our friends and allies a large number of persons from Asia and Greece, who happened at the time to be serving on deputations, beheld in our forum the revered image of their gods that had been carried away from their own sanctuaries and recognising as well the other statues and works of art, some here, some there would stand gazing at them with weeping eyes objects wrenched from our allies by criminals and robbers.

C ICERO, INDICTING V ERRES

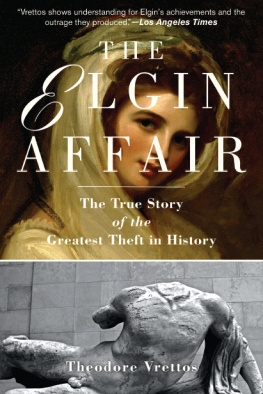

A s long ago as 70 BC the case against the looters of artworks was put by the great Roman barrister in his prosecution of Gaius Verres, whose plunder of Sicily while he served as Roman governor in peacetime bears some similarity to more modern spoliations: of India by the East India Company; of Greece by Lord Elgin; of China by his son; and of African kingdoms by the armies of Britain, France, Belgium, Germany and Portugal. Cicero was not merely a great advocate, but a legal philosopher who worked into his arguments (more usually, for the defence) a broader view of what justice requires. Verres had used his three-year term as governor of the Greek province of Sicily to seize public as well as private artworks on a massive scale (he said he needed to do this for one year to make his own fortune, for a second year to reward his cronies, and for a third to bribe his jury). He had decorated his own home with his thefts, and some had gone on display in the Forum the Roman Empires open-air equivalent of the British Museum. This could be no justification, Cicero explained, for robbing a people of their heritage, their temple sculptures, their public monuments, their tapestries, their furniture, even their domestic dinner services. Justice required punishment. After listening to Ciceros opening speech, Verres fled Rome and could never return from banishment: his estate was ordered to pay compensation to his victims for his thefts.

Ciceros speech, and others that he would have delivered had the trial continued, were published and have echoed down the ages. articulated the principle that representatives of an occupying power had no right to take, or to purchase at an undervalue, cultural items of significance to the people of those territories. It was pointless for Verres to contend that his acquisitions had been gifts or willingly sold at a low price no individual citizen and no city would willingly part with such cherished mementoes. For Cicero, art had an importance as heritage which could only be fully appreciated in its true and original context: well might the Sicilian deputies weep and demand justice when they saw their statues on display in a foreign museum. He represented them in court, and they had their retribution when Verres fled from hearing his words.

* * *

This is a book about culture the word that made Hermann Gring reach for his gun and Chairman Mao misdescribe a revolution which almost destroyed it. It is about how people can lose or misunderstand the heritage of their own country when it is kept under lock and key in foreign museums. Their experience of seeing it abroad is akin to that of the Sicilian deputies described by Cicero, who would stand gazing with weeping eyes, full of shame at the loss of their gods, their civic spirit, their public pride, and their human right to enjoy their heritage. Yet remedy for loss is unavailable today: mighty encyclopaedic museums like the Met and the British Museum and the V&A and the Louvre and the Getty and soon the Humboldt Forum lock up the precious legacy of other lands, taken from their people by wars of aggression, theft and duplicity, and there is no forum to which they can turn to get them back, at least if they were wrongfully obtained before 1970, the date of UNESCOs first and only convention on the subject. This means the most valuable treasures of antiquity are withheld from the people whose ancestors created them and which could inspire their youth anew with the story they tell and the knowledge that their progenitors could once create such beauty.

Personally, I love museums and visit, as a tourist, whenever I can to get that gee whiz experience that Wow, they did that 3,000 years ago! kind of feeling on looking at an object that actually witnessed history in the making, or contributed to it: Tolstoys typewriter, Churchills half-smoked cigar, the blood-flecked stretcher that carried the body of Che Guevara or the rock on which Jesus Christ rested his head (or was said to a qualification one must always make about relics in Jerusalem). I was much struck, on a recent trip to Cubas National Museum, to see the Granma, that small fishing boat bought by Fidel Castro from a Texan dentist, which took his gang of eighty desperados on their historic voyage from Mexico to Cuba, to defeat the might of the American-backed military, and to face down America itself. The boat is well guarded in the museum and evocative you can imagine Fidel and Che arguing in the captains tower but only when you get round to reading your Lonely Planet guidebook do you realise you have been fantasising over a replica the real boat disappeared long ago. Does that make the experience you had at the time less valid? Were the British Museum to return its sacred moai to Easter Island, taken by its navy without permission, and replace the statue with an exact replica (one has been offered in exchange by the Rapa Nui people), it would still provide the museums favourite selfie spot. It would exemplify Rapa Nui sculptorship without wrenching away the spirit of the heroic ancestor on whom it was modelled.

The real thing has a special meaning for those from whom it has been stolen, which cannot be shared by tourists who pass it in a Western museum. It is the difference, I suppose, between hearing a famous rock group and a rather good tribute band in the latter case, something is missing: the awe that comes from authenticity. To which is added a further emotion, a sense of national pride, or at least of justice, if the heritage object has come home, not merely on loan (which Western museums sometimes offer to excuse their thefts) but as possessions of the people from whom they once were taken. Offering stolen heritage back on loan for however long is a post-colonial insult.

Love of country can produce dreadful and deadly consequences, which have nothing to do with the rights of people to possess and enjoy their own heritage. Im a nationalist, OK? says President Trump as he exhorts his base. Use that word! They do, but in a way which conduces to populism, that far-right feeling that has produced Trump and Brexit and Modi and Orbn and Bolsonaro, and has left white, English-speaking progressives having to choose, if they want to live under a good government, between Canada and New Zealand. There is nothing wrong in allowing people of every modern state some pride in it, and in its place in the world, by seeing their own history through the heritage objects that have been witness to it. It is important to distinguish between history and heritage: the former is the story of the past told as accurately as present information allows (future discoveries may amend it), while the latter symbolises and enlivens the past but is purposely a celebration (sometimes, a mourning) of it, a profession of faith in a past tailored to present-day purposes. For a museum visitor in another country, it does not matter or matter so much whether the object is an original or an exact copy the feeling it evokes is much the same appreciation, without the sense of possession and pride. That is what Cicero tried to explain to a Roman jury that liked its triumphs and its Forum exhibition of the spoils of its empire: theirs are fleeting and evanescent feelings, compared to those of the people who must grieve for their loss and demand justice for the crime of their despoliation. As a tribute to this greatest of barristers, we should devise a law that would be the logical conclusion of his argument: a law providing for the repatriation of wrongfully taken cultural property.