How parts of the Parthenon frieze came to be in England in the first place is an example of imperial arrogance manifest in marble. Wider still and wider shall thy bounds be set not content with claiming sovereignty over other peoples countries, the British Empire appropriated the art in which the ethos, history, religious mythology, the fundament of the people is imbued. The ethics of a British national museum, in the early nineteenth century, in buying the heritage of another country without concern of how and by whom it came to be on sale, were evidently countenanced, despite some controversy, in the name of this same imperial arrogance.

But that is the past. Restitution now, in the twenty-first century, is on wider (appropriately) than legal grounds, grounds of dishonesty in colonialism justified as the acquisition of art.

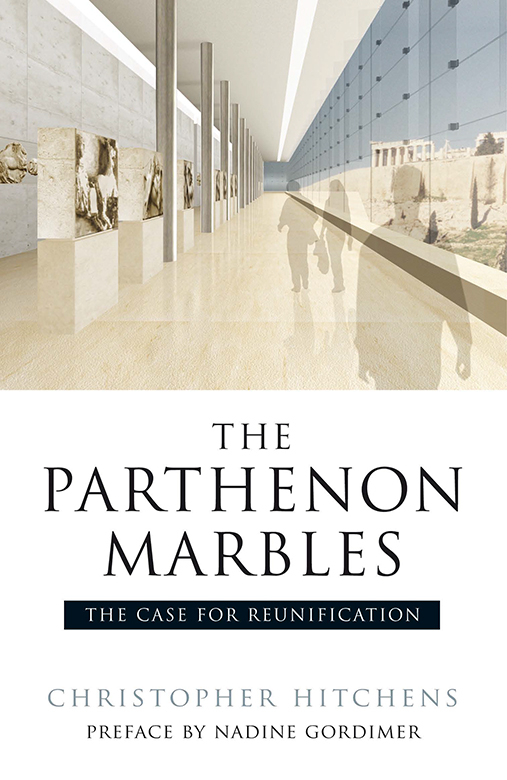

We should start by ceasing to speak of the Elgin Marbles. They are not and never were Lord Elgins marbles; that is not their provenance. As is so exigently researched and set out in this book, they are sections of the Parthenon marbles that Lord Elgin, British Ambassador to Greece during the late Ottoman regime, had hacked out of the antique frieze in the Parthenon on the Acropolis in Athens. In terms of origin, the claim is absolute: they belong to Greece. But as representative of the culture of ancient Greece, as the genesis of the ideal of humanism and beauty in art, there is also the argument that the Parthenon frieze belongs to world culture, to all of us who even unknowingly derive something of our democratic aesthetic from it. From that argument derives another: where in the world should such art, universally owned in the sense of human development, be displayed? Where will the inspirational sight be available to the majority of us? The answer the British Museum in London harks back to that relic of Empire, the assumption that Britain is the mecca of the world; that the sections of the Parthenon frieze shown there can be seen by more people, from more parts of the globe, than is possible anywhere else. I do not know the comparable figures for visitors to Athens and London. I do know, as one among millions of others who live neither in England nor in Greece, that neither great city is a venue for a casual Sunday afternoon cultural outing. For the majority of the world population, both cities are equally unlikely destinations. Even for those fortunate enough to have the means to travel, a choice of either destination is decided by an itinerary: both are abroad, far away. So whether more people see the Parthenon marbles in isolation from their living context in London, than do others who see them in Athens, is a criterion for the privileged of where they should be. They belong: they are the DNA, in art, of the people of Greece. If they also belong, as they do, to all of us who have inherited such evidence of human creativity as development, and there is no site in our world where the direct experience of seeing them is achievable for everyone, where else should they be but where they were created?

One of the reasons, other than the specious one of availability, that is presented by those who demand to keep the Parthenon marbles in the British Museum, is that returning them to their country of origin would begin a forced exodus of foreign treasures from all museums where great ones are held. Certainly this would seem to deny the purpose of art museums: to further appreciation of the universality in diversity of art as profound human expression, in different visions, by different peoples occupying varied environments in past and present times. Setting aside this sweeping conclusion of empty museums, one would accept as reasonable that examples of art from other cultures, objects complete in themselves, not plundered from their essential context but legally purchased objects that exist in many surviving examples in their countries of origin, could be honourably retained by foreign museums.

Objects complete in themselves that is unquestionably a decisive criterion in the case of the Parthenon marbles. The Elgin marbles are sections, chapters in stone, excised from a marvel, narrative brutally interrupted, some isolated in the British Museum, others, incomplete in their sequence, in their rightful place in Athens. The magnificent coherence of one of the greatest works of art incredibly still in existence is, as art and in its meaning as a unit, denied and destroyed. The frieze that survived invasions, conquests, the desecration by Christian and Muslim religious regimes, 300 years of rule by another empire (the Ottoman) this has been torn apart. Fortunately the coherence can and must be restored. The return of the marble chapters of the Parthenon frieze narrative from the British Museum to Greece will be fulfilment for Greece and for world heritage.

There is an argument for the retention of great irreplaceable works of artistic genius that is as old, if not older, than that put forward in defence of Lord Elgin. And it has some credence. In many eras and countries, exquisite works have been vandalised in conflicts political and religious, while the conditions of neglect in which some are kept now, endangering their survival, seem to be justification for pillaging them for the benefit of foreign museums that can afford to protect and preserve the works in controlled environments. There they are displayed with pride in halls, complete with labels identifying their significance in the beliefs, arts, social and political organisation of their distant place and time. Continuity of that place and time in the living people of the countries of origin, ofcourse, is ofno consideration to the museums directors.