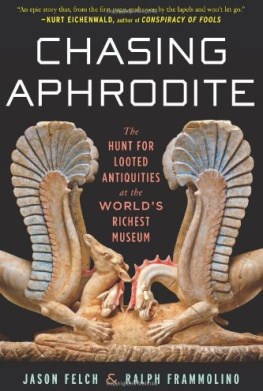

Chasing Aphrodite

The Hunt for Looted Antiquities at the World's Richest Museum

Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino

Table of Contents

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN HARCOURT

BOSTON NEW YORK

2011

Copyright 2011 by Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company,

215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Felch, Jason.

Chasing Aphrodite: the hunt for looted antiquities at the world's

richest museum / Jason Felch and Ralph Frammolino.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-15-101501-6

1. Classical antiquitiesDestruction and pillage. 2. Cultural property

RepatriationItaly. 3. Cultural propertyRepatriationCaliforniaMalibu.

4. J. Paul Getty MuseumCorrupt practices. I. Frammolino, Ralph. II. Title.

CC 135. F 46 2011

930dc22 2010025835

Book design by Victoria Hartman

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Photo credits appear on .

For Nico

J.F. For Allyson and Anna

R.F.

Contents

P ROLOGUE

Part I Windfalls and Cover-ups

1. T HE L OST B RONZE

2. A P ERFECT S CHEME

3. T OO M ORAL

4. W ORTH THE P RICE

5. A N A WKWARD D EBUT

6. T HE W INDBLOWN G ODDESS

7. T HE C ULT OF P ERSEPHONE

Part II The Temptation of Marion True

8. T HE A PTLY N AMED D R . T RUE

9. T HE F LEISCHMAN C OLLECTION

10. A H OME IN THE G REEK I SLANDS

11. C ONFORTI'S M EN

12. T HE G ETTY'S L ATEST T REASURE

13. F OLLOW THE P OLAROIDS

14. A W OLF IN S HEEP'S C LOTHING

Part III "After Such Knowledge, What Forgiveness? "

15. T ROUBLESOME D OCUMENTS

16. M OUNTAINS AND M OLEHILLS

17. R OGUE M USEUMS

18. T HE R EIGN OF M UNITZ

19. T HE A PRIL F OOLS' D AY I NDICTMENT

20. L IFESTYLES OF THE R ICH AND F AMOUS

21. T RUE B ELIEVERS

22. A B RIGHT L INE

E PILOGUE: B EYOND O WNERSHIP

Acknowledgments

Notes

Further Reading

Index

Prologue

I N RECENT YEARS, several of America's leading art museums have given up some of their finest pieces of classical art, handing over more than one hundred Greek, Roman, and Etruscan antiquities to the governments of Italy and Greece. The monetary value of the returned objects has been estimated at more than half a billion dollars. The aesthetic loss to the nation's art collections is immeasurable. Several of the objects have long been hailed as the defining masterpieces of their era. Yet for the most part, the museums gave up these ancient sculptures, vases, and frescoes under no legal obligation and with no promise of compensation. After decades of painstaking collecting, why would they be moved to such unheard-of generosity?

The returns followed an international scandal that exposed an ugly truth, something art insiders had long known but publicly denied. For decades, museums in America, Europe, and elsewhere had been buying recently looted objects from a criminal underworld of smugglers and fences, in violation of U.S. and foreign law.

The museum world's dirty little secret came to light amid revelations about pedophile priests in the Catholic Church and widespread steroid use in major league baseball. Like those scandals, the truth about museums and lootingdocumented in blurry Polaroids and splashed across newspapers around the worldredefined some of America's most cherished institutions in the public mind. Museums have long been our civic temples, places to worship beauty and the diversity of the world's cultures. Now they are also recognized as multimillion-dollar showcases for stolen property.

The crime in question, trafficking in looted art, is hardly new. Indeed, it is probably the world's second-oldest profession. One of the earliest known legal documents is an Egyptian papyrus dating to 1100 B.C. that chronicles the trial of several men caught robbing the tombs of pharaohs. (The document resides not in Egypt, of course, but in London, after being "acquired" by the British Museum in the 1880s.) The Romans sacked Greece; Spain plundered the New World; Napoleon filled the Louvre with booty taken from across his empire. In the eighteenth century, caravans of British aristocrats on the grand tour blithely plucked what they wanted from ancient sites, sending home wagonloads of ancient art for their country estates.

This long parade of plunder has occasionally been interrupted by outcry and debate. In 70 B.C. , a sharp-tongued Roman attorney named Cicero summoned all his oratorical skills to press a criminal case against the corrupt governor of Sicily, Gaius Verres, whose wholesale sacking of temples, private homes, and public monuments bordered on kleptomania.

"In all Sicily, in all that wealthy and ancient province ... there was no silver vessel, no Corinthian or Delian plate, no jewel or pearl, nothing made of gold or ivory, no statue of marble or brass or ivory, no picture whether painted or embroidered, that he did not seek out, that he did not inspect, that, if he liked it, he did not take away," Cicero told the Roman Senate. Looting was "what Verres calls his passion; what his friends call his disease, his madness; what the Sicilians call his rapine."

In 1816, more than eighteen hundred years later, a similar condemnation echoed throughout the halls of the British Parliament after Thomas Bruce, Seventh Earl of Elgin, returned from Greece with shiploads of exquisitely carved friezes ripped from the Parthenon. The marbles represented the artistic zenith of ancient Greece and had survived for twenty-two centuries. Their removal represented the nadir of antiquities collecting. Even Britain's wealthy cognoscenti, men who had feasted on marble trophies from Greece and Rome for more than a century, recoiled at the magnitude of Lord Elgin's appetite. The most stinging rebuke flowed from the quill of Lord Byron, Elgin's contemporary and a great defender of Greek culture. In his poem "The Curse of Minerva," Byron gives voice to the goddess herself to denounce the intrepid collector:

I saw successive Tyrannies expire;

'Scaped from the ravage of the Turk and Goth,

Thy country sends a spoiler worse than both.

Britain eventually bought the marbles from Elgin and installed them in the British Museum, the first of the so-called encyclopedic museums. It was soon joined by the Louvre, the National Museums in Berlin, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, these repositories of human achievement accumulated some of the world's most celebrated works of art, many of which might otherwise have been lost. The museums pioneered new ways to protect and conserve them and spent millions building palatial galleries in which to display them. They saw themselves as products of the Enlightenment, brick-and-mortar extensions of Diderot's Encyclopdie. But they were also the products of colonialism, driven to collect by a sense of cultural superiority that justified the unchecked acquisition of relics from the far reaches of their empires.

In America, this attitude prevailed well into the postWorld War II boom years, when prosperity gave rise to a new class of regional museums and nouveau riche art enthusiasts who adopted the role of the enlightened collector. Many sought to make their mark in the niche of classical antiquities, which conveyed instant prestige and seemed to yield a never-ending supply of new masterpieces.

The sudden demand for antiquities fueled looting as never before, not just in Mediterranean countries but also across Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia. What had long been a small market in trinkets for tourists rapidly became a sophisticated global supply chain. Illegal excavations destroyed archaeological sitesand the historical record they containedat a staggering pace.

Next page