Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

REASSEMBLING MOTHERHOOD

REASSEMBLING MOTHERHOOD

PROCREATION AND CARE IN A GLOBALIZED WORLD

EDITED BY

YASMINE ERGAS, JANE JENSON, AND SONYA MICHEL

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New YorkChichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2017 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53807-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ergas, Yasmine, editor. | Jenson, Jane, editor. | Michel, Sonya, 1942 editor.

Title: Reassembling motherhood : procreation and care in a globalized world / edited by Yasmine Ergas, Jane Jenson, and Sonya Michel.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017005586 (print) | LCCN 2017022195 (ebook) | ISBN 978-0-231-53807-7 (e-book) | ISBN 978-0-231-17050-5 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Motherhood. | Human reproductive technology. | Child rearing. | Families.

Classification: LCC HQ759 (e-book) | LCC HQ759 .R425 2017 (print) | DDC 306.874/3dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017005586

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

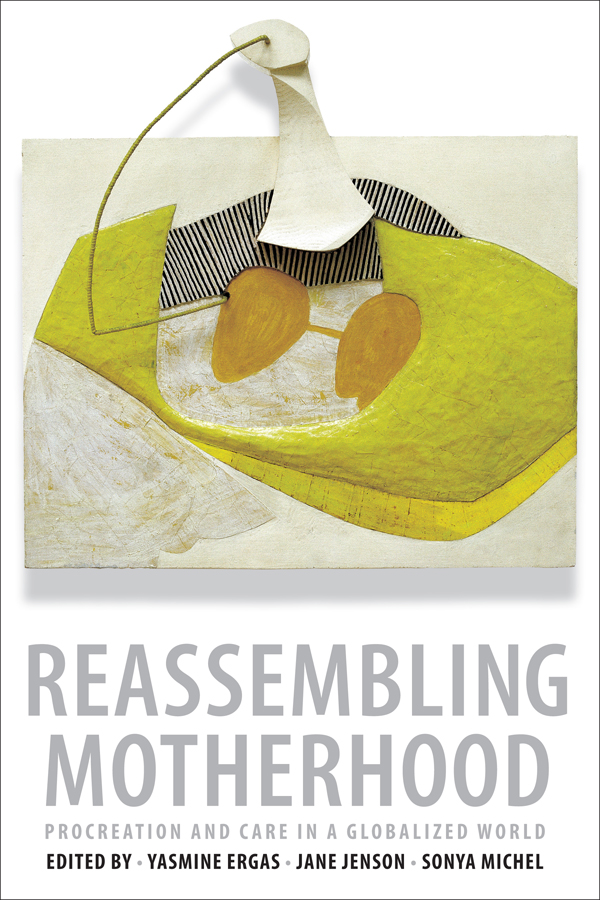

Cover design: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

Cover image: Eva Hesse, H + H. June 1965. Hauser & Wirth Collection / The Estate of Eva Hesse. Courtesy of Hauser & Wirth Collection.

TO RACHEL (RIKKI) MIHAELOFF ERGAS

CAIRO, JULY 3, 1927NEW YORK, JULY 30, 2014

IN LOVING MEMORY

CONTENTS

YASMINE ERGAS, JANE JENSON, AND SONYA MICHEL

NARA MILANICH

LINDA G. KAHN AND WENDY CHAVKIN

CLAIRE ACHMAD

LETIZIA PALUMBO

YASMINE ERGAS

ANNE HIGONNET

CAROL SANGER

PIEN BOS

DOROTHY ROBERTS

MARTHA ALBERTSON FINEMAN

SONYA MICHEL AND GABRIELLE OLIVEIRA

HELMA LUTZ

JANE JENSON

ALICE KESSLER-HARRIS

T his book began with an intuition: motherhood as a set of practices and understandings is being transformed by the convergence of globalization, reproductive technologies, and shifts in gender relations. The book examining this transformation has benefited from the expertise and support of many whom we wish to acknowledge here. Yasmine Ergas organized an interdisciplinary workshop at Columbia University, called Deconstructing and Reconstructing Mother: Regulating Motherhood in International and Comparative Perspective, which met twice in 2012. We are grateful to the scholars who participated in that workshop; their contributions to the discussions helped to inform the papers that ultimately became chapters in this book.

Peter Bearman, then director of the Institute for Social and Economic Research and Policy (ISERP), now of the Interdisciplinary Center for Innovative Theory and Empirics (INCITE), and Elazar Barkan of the Institute for the Study of Human Rights (ISHR) at Columbia University supported this endeavor from the start. Without their confidence, this project could not have happened; thank you, both. Invaluable logistical help and advice were provided by Ariella Lang (ISHR) and Michael Falco (ISERP). Jennifer Hirsch (Columbias Mailman School of Public Health) played a key role in preparing the ISERP grant application, and Alessia Lefebure (Alliance program, Columbia University) provided additional financial support. We are grateful to you all.

At Columbia University Press, we thank Anne Routon, the editor who saw the potential of this book from the beginning, and her dedicated staff. We also acknowledge the help provided by the external reviewers, who generously gave invaluable feedback and careful, knowledgeable, and insightful comments.

Inevitably, working on motherhood harks back to our personal experiences. As it happens, we all have daughters. One of them became a mother herself as this book was being finalized. From our daughters and sons, we learn how to be mothers. Together with our partners, they help us to think motherhood; together, we invent and reinvent its practices. Luckily, we also laugh together. Yasmine is especially grateful to Lenny and Sofia for their patience and good humor through many conversations over the meaning of what, after all, is a role that they might have just expected her to fulfill. Jane thanks Bridget and George for their help in understanding one of lifes most rewarding roles. Sonya thanks Josh, Colin, and Nadja for introducing her and Jeffrey to the joys of grandparenthood.

Before our own mothering beginsand, if we are lucky, even as it is ongoingwe learn from our mothers. Yasmines mother, Rikki Ergas, attended the first meeting of the workshop. We are grateful she was there to help launch this project.

YASMINE ERGAS, JANE JENSON, AND SONYA MICHEL

M other as an identity and a role is undergoing rapid change. There long have been multiple avenues to motherhood, including adoption and fostering, yet conventionally a mother has been understood to be a woman who both bears and cares for a child. Today, however, the status of mother may be conferred on a person who fulfills only one or even neither of these roles. Changing social norms, reproductive technologies, including assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs), and the possibilities offered by globalized personal services all have led to the creation and expansion of markets in both procreation and care. As a result, women who previously could not bear children may now do so, and those who cannot or do not wish to physically reproduce may foster, adopt, or engage a surrogate mother who will bear a child on their behalf. Men, too, may access the markets in procreation and advance claims to being mothers rather than simply parents. In addition, global as well as local labor markets now provide childcare workers, without the women who hire such workers ceding any of their status as their childrens mothers.

In other words, as increasing numbers of women who are not going to be considered mothers give birth and care for children, and as women who claim the status of mothers perform only one or neither function, neither parturition nor care is either necessary or sufficient to define a mother. Instead, large social processes are at work, creating chains of procreation and chains of care. ARTs are redefining who may procreate, whether by direct gestation or through surrogacy, and with what or whose genetic material, while states struggle to define which of the new pathways to procreation should legitimately endow a woman with the status of mother. At the same time, paid care workers are assuming a major presence in the lives of children, while public policy shapes the means and ends of care.

Changes in social norms and public policy as well as in legal rights and technologies, and the development of markets in both procreation and care, mean that motherhood has become a choice for more women. In this sense, there is what we might think of as a liberalization of motherhood. But the new panoply of choice is not, of course, available everywhere and to everyone. Motherhood has not been fully democratized. The possibility of choosing how to mother is not equally available to everyone, either within any one society or across different countries. Compulsion and coercion, exclusion and privilege persist; the opportunity to decide to bear children (or not) or how to organize the care of those children is unevenly distributed. Restrictive policies, socioeconomic disadvantage, cultural mores, and discrimination founded on multiple bases force some women into motherhood while preventing others from either bearing or caring for their children. The chapters in this volume examine the inequalities that affect the distribution of choice as well as the ways in which more choice has been generated within the two chains of procreation and of care.