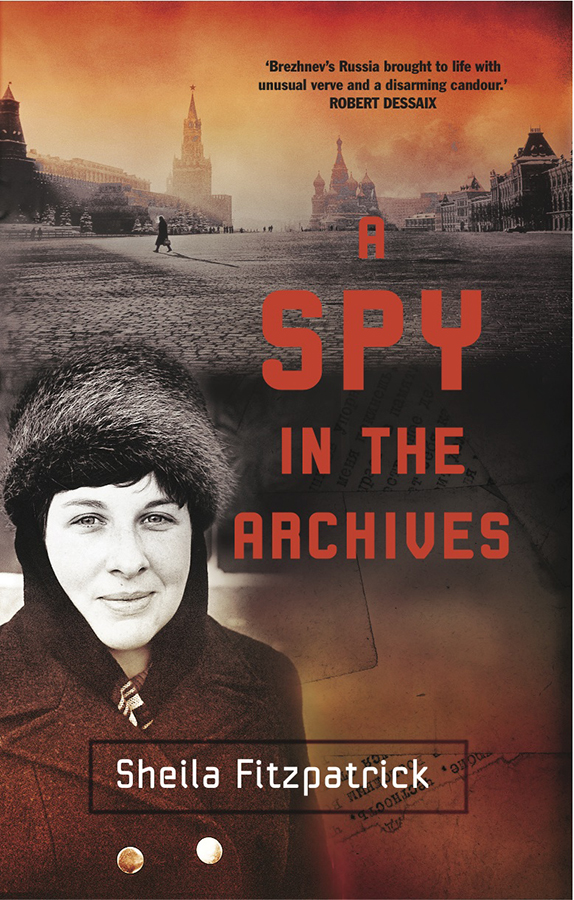

Fitzpatrick - A Spy in the Archives

Here you can read online Fitzpatrick - A Spy in the Archives full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Melbourne, year: 2013, publisher: Melbourne University Publishing, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A Spy in the Archives

- Author:

- Publisher:Melbourne University Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- City:Melbourne

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Spy in the Archives: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A Spy in the Archives" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A Spy in the Archives — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A Spy in the Archives" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

PRAISE FOR

A SPY IN THE ARCHIVES

The vanished world of Brezhnevs Russia brought to life with unusual verve, a disarming candour and a shrewd eye for the telling detail. Robert Dessaix

Sheila Fitzpatrick single-handedly set in motion the renewal of Soviet studies: instead of the Cold War Manichean reports on the horrors of Stalinism, she delivered vivid portrayals of what did it effectively mean to be an ordinary citizen of the Stalinist Russia. A Spy in the Archives is the insanely readable crowning achievement of her distinguished career, a book every historian should dream to write. Through the autobiographic report on her visits to Soviet Union, she tells a story of bureaucratic hassles but also of deep and lasting personal friendships. One gets a touching picture which renders the taste of everyday life and its small pleasures without obfuscating the nightmares of a totalitarian state. If A Spy in the Archives will not become a bestseller, then there is something seriously wrong with our culture! Slavoj Zizek

To Igor and Irina, in memoriam

Contents

At the Spy College

I was a student at Oxford writing a doctoral dissertation in Soviet history when I was outed as a spy in a Soviet newspaper. Or at least the next thing to a spy. According to the newspaper, I was one of those scholars who pretend to be doing scholarly research but are actually putting out disinformation, the way intelligence agents do. My work was simply provocation, a dishonest game, whose purpose was to obscure the truth. My activities differed little from the ploys of bourgeois spies; I was an ideological saboteur.

I didnt intend to be an ideological saboteur, whatever that might mean. I was in Moscow in June 1968, near the end of my second stint as a British exchange student, and all I wanted to do was get on with my archival research and be able to come back to the Soviet Union in the future to do more. I was passionate about my research and fascinated, in a non-admiring way, by the Soviet Union. But this was the period of the Cold War, and relations between the Soviet Union and the West were full of tension and mutual accusations. Anybody who worked on the Soviet Union was at risk of being seen by the Soviets as a spy. But when they actually accused you, the consequences were likely to be serious.

The cause of offence was my first scholarly article, published the previous year in a sober academic journal called Soviet Studies . It required some imagination to see my article in such a light: it was bibliographical, with the prosaic title AV Lunacharsky: Recent soviet interpretations and republications. Lunacharsky, the first Soviet Peoples Commissar of Enlightenment after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, was the subject of my dissertation. My article wasnt even anti-Soviet by the standards of the time. Almost certainly it was not the content of the article that upset the Soviets but the fact that the authors name was followed by my academic location, St Antonys College, Oxford. St Antonys was often referred to in the Soviet Union, and in the West, too, as a spy college, meaning that a number of the Fellows had worked for British intelligence in the past, and were presumed to retain some ties in the present. The colleges Russian Centre, particularly my supervisor, Max Hayward, the translator of Dr Zhivago , was in Soviet bad books for publicising writers in trouble with the regime and associating too closely with the Congress for Cultural Freedom in London and its alleged CIA sponsors.

Being outed as the next thing to a spy would really have upset me if I had known about it. I would have expected to find the KGB on my doorstep in Moscow informing me of my expulsion from the country, with the British Embassy hovering nearby to make sure I got out quickly. But fortunately I didnt read the newspaper, a particularly conservative one, and neither did any of my Russian friends nor, apparently, anyone from the embassy, so it passed unnoticed. The Russian friends might not have picked it up anyway, because they knew me by my married name, Sheila Bruce. Also, of course, they knew me to be a woman, whereas the newspaper thought S Fitzpatrick was a man. Whether the KGB, which presumably inspired the newspaper article, knew that Sh Bruce of the British Council Exchange (Sh is one letter in Russian) and S Fitzpatrick of St Antonys were one and the same remains unclearthough, if they didnt, shame on them for professional sloppiness. St Antonys comes out better from this Cold War story, professionally speaking, than the KGB: at least they were reading the Soviet press carefully enough to notice the article and tell me about it when I got back to Oxford that summer. I dont remember who gave me the news; I just remember my reaction, which was horror.

From a St Antonys standpoint, it wasnt that big a deal to have the Soviets throwing spying accusations at the college; it happened so often. But it was different for me than for Max Hayward and the other Russian Centre Fellows. Most of them were already persona non grata with the Soviets and therefore didnt go to the Soviet Union, which during the Cold War was very touchy about letting foreigners behind the Iron Curtain. I was a historian at the beginning of my career, and I needed Soviet archives and libraries to keep on doing the kind of work I wanted to do. In addition, I had made very close friends in Moscow and didnt want to lose touch with them: these relationships were shaped, no doubt, by the political context but transcended them, becoming bonds for life.

I had been bitten by the Moscow bug, like a number of my contemporaries on the student exchanges. The Soviet Union might be the most uncomfortable, inconveniently organised place imaginable, xenophobic and even dangerous at times, with an obstructive and suspicious bureaucracy to drive you mad, but we had managed to get to this exotic country, and had the almost unique status among resident foreigners of living among Russians, not in special foreign enclaves. We felt like cosmonauts who had landed on the moon: the question of liking or disliking the place was irrelevant. Students bitten by the Moscow bug were not content with a single year on the exchange, but did their best to return, as I did in two successive years. I explained it in a letter to my mother as being like soldiers in wartime, desperate to get back to the front.

I probably had a better background knowledge of spying than I did of Russian history when I set off to England in 1964 to study Soviet history and politics. They didnt teach Russian history at the University of Melbourne in my day. They did teach Russian, however, in a department headed by my parents friend Nina Christesen, and I took two years of it, which was enough to read the language, but not very well. I wouldnt have admitted myself to graduate school later, when I was a professor of Soviet history in America, but Oxford in the 1960s had no qualms. Oxfordwhich offered no courses in modern Russian history, and only Old Church Slavonic on the language sidewas not really in the business of teaching its postgraduates anything. Cynically, one could say that it was a matter of hanging around to absorb the atmosphere and leaving with a brand-name degree in your resume. As one of the (lower-status) spies among my Oxford acquaintances remarked, Oxford is a fine place to have been because you can always come back, even if they dont like you.

My background knowledge of spying came from growing up in a left-wing family in Melbourne in the Cold War. I was nine when Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were convicted in the United States of being spies who passed on the secrets of the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union, and eleven in February 1953 when, despite worldwide protests, they were executed. My father, Brian Fitzpatrick, a civil liberties activist, was active in the local campaign to save them from execution, and I had no doubt that this just cause, supported by so many of the great and good throughout the world, would be victorious. As the execution date neared, we listened regularly to the bulletins on the radio, and I was sure that, as in any good radio serial, there would be a last-minute reprieve. It was a big shock when the reprieve didnt come, and I had to adjust some assumptions about how the world works. I was left with a certain puzzlement about my fathers professed conviction that the Rosenbergs were innocent. They were Communists, which according to my father was OK, though at school people thought otherwise. As Communists, they believed that the Soviet Union was a better country than the United States; and theyand my father, toothought the world would be a safer place if both superpowers had the bomb. So why shouldnt they have passed over atomic secrets? And if this was spying, what was so terrible about being a spy?

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «A Spy in the Archives»

Look at similar books to A Spy in the Archives. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A Spy in the Archives and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.