Introduction

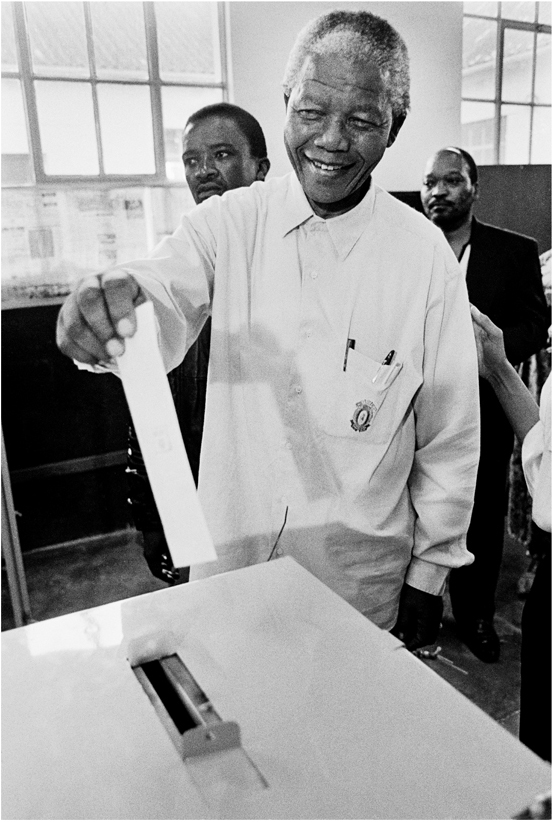

FIGURE 1. Nelson Mandela casts the first ballot of his life, 1994.

I DO NOT KNOW HOW THINGS will be by the time you read it, but this book goes to press at a grim moment. After spending much of my life writing either about forms of tyranny that weve seen vanish, like apartheid in South Africa or communism in the Soviet Union, or that belonged to earlier centuries, like colonialism or slavery, it is a shock to feel the ruthless mood of such times suddenly no longer so far away. As I write, much of Europe is awash in a bitter stew of revived nationalism, anti-Semitism, and hostility toward Muslims and refugees. Around the world, many a country that was once a democracy, or seemed on the path to being so, has turned repressive. From Poland to the Philippines, Hungary to India, Turkey to Russia, autocrats with little tolerance for dissent are riding high.

Worse yet is that we Americans have elected a president who makes no secret of his enthusiasm for such strongmen and, with nothing but mockery for his critics and contempt for the constitutional separation of powers, would clearly like to be one himself. Donald J. Trump has bent and twisted the truth like pretzel dough, claimed his predecessor was born in Kenya, likened Africa to a toilet, slammed Mexicans as rapists and Haitians as all having AIDS, and included in a reference to very fine people the toxic collection of white nationalists, neo-Nazis, and Ku Klux Klan members who gathered in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017. One of these very fine people killed a woman and injured many others by ramming his car into a crowd. Almost day by day, Trumps racism becomes more naked and his enthusiasm for torture, the death penalty, and nuclear weapons more strident. He has done his best to undermine the investigation into his Russia dealings and called Democrats who failed to applaud his 2018 State of the Union speech un-American. This list could be far longer. Gun lovers, conspiracy mongers, and the mushrooming array of camouflage-clad private militias in this country are energized in a way they have not been for decades.

Around the world, not just the present but the past has become a battleground. Those right-wingers were in Charlottesville to protest a plan to remove a statue of the Confederate General Robert E. Lee. In Hungary, a German ally in the Second World War, monuments have been installed and museum exhibits altered to portray Hungarians, not Jews, as victims of the Nazis. In the 1990s, many Russians told me of their hope that a few of the old Soviet labor camps could be preserved or restored as memorials to those who died and reminders that such events must never happen again. Instead, at the only place where a restoration has been completed, near Perm, in the Ural Mountains, the camp has become a site of pilgrimage for enthusiastic followers of Vladimir Putin who want to celebrate the glorious days of Stalins rule.

We have some tough years ahead of us. The title piece of this collection, about Americas early twentieth-century red scare, could just as well be called Lessons for a Dark Time. But when times are dark, we need moral ancestors, and I hope the pieces here will be reminders that others have fought and won battles against injustice in the past, including some against racism, anti-immigrant hysteria, and more. The Trumps and Putins of those eras have gotten the ignominy they deserve.

A few words about what youll find in these pages:

Ive chosen the articles for this book from a much larger number Ive published over the past two decades or so. Most have to do with the forces that have prevented us, today or in earlier centuries, from living in a fairer and more humane world. Some are about people who tried to bring that world closer; others deal with writers who explored the injustices of their times. Some of whats here reflects my travels: you wont find Cannes or Tuscany, but you will find a prison in Finland, descendants of slaves gathering in a London park, and a day on the campaign trail with Nelson Mandela. Sadly, many of the men and women whose voices I was privileged to hear are no longer with us: Mandela, of course, plus the environmentally pioneering architect Laurie Baker, the Gulag survivor Nadezhda Joffe, anddying much too young of a heart attack while weakened by malariathe brave Congolese crusader against rape, Masika Katsuva.

What has drawn me to such people, I think, has a lot to do with coming of age in the early 1960s, a decade that left its mark on so many of us. In Washington, the president was a young John F. Kennedy, who, despite his flaws, inspired a wave of hope and idealism unlike any this country has seen. In the South, the civil rights movement was reborn, awakening tens of millions of Americans to the harsh wrongs that should have been ended by the Civil War. As fellow college students of mine returned from freedom rides to desegregate Southern bus terminals, I saw that there was a world of ferment outside the campus, and I was hungry to explore it. And then, like all men subject to the draft, I found the Vietnam War looming over me and had to ask whether I was willing to risk my life in a senseless conflict on the other side of the globe. Living through that time gave me a lifelong interest in people who took a stand against despotism, who spoke out against unjust wars, or who saw the evils of institutions like slavery or colonialism when, all around them, others took such things for granted. Those are the kinds of subjects Ive always been drawn to write about.