Table of Contents

Guide

Photo Fibonacci Blue

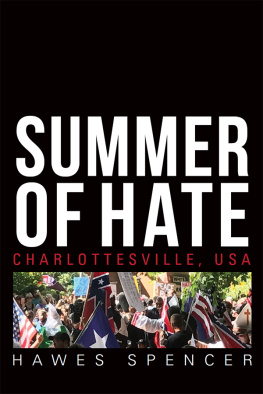

To all who defended democracy at Emancipation Park on August 11 and 12, 2017.

Published by Public Seminar Books in association with OR Books.

2018, 2019 Public Seminar Books

The partial reproduction of this publication, in electronic form or otherwise, is consented to for noncommercial purposes, provided that the original copyright notice and this notice are included and the publisher and the source are clearly acknowledged. Any reproduction or use of all or a portion of this publication in exchange for financial consideration of any kind is prohibited without permission in writing from the publisher.

Public Seminar Books

79 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10003

publicseminar.org

Public Seminar and Public Seminar Books are significant innovations in academic publishing: slow news and fast books, using the advanced design and social science resources of the New School. They also flow out of a deep intellectual-political tradition of the New School and its engagement with the problems of the times and enduring problems of the human condition: the struggles for cultural freedom and democracy against tyranny.

Book interior design by Juliette Cezzar

All rights information:

First trade printing 2019

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-949017-00-7 paperback

ISBN 978-1-949017-01-4 e-book

Published for the book trade by OR Books in partnership with Counterpoint Press.

Distributed to the trade by Publishers Group West.

Table of Contents

#CHARLOTTESVILLE is the first in a series to be published by Public Seminar Books, an initiative that expands the digital Public Seminar vision to re-imagine and re-constitute the relationship between academic life and the broader public. Knowing that organized, critical perspectives were needed after the events of August 11 and 12, we responded to the urgency of the moment by re-editing essays published over the course of fall 2017, and soliciting several new essays. The horrors of racism vividly and tragically appeared in a particular place, at a particular time, as events of the day, but understanding what happened there then requires confronting enduring problems of the human condition.

We will continue to experiment with content, form, and publishing styles, as we reaffirm and expand the project of the New School for Social Research, and test the limits of what twenty-first century publishing can look like. The mission of Public Seminar informs the inquiries here: confronting the pressing issues of the day and the fundamental problems of the human condition, in open, critical, and challenging ways. This volume is an invitation to continue observing, thinking about, and acting against the legacies of slavery and racism in Charlottesville, in Virginia, in the United States, and far beyond.

Jeffrey C. Goldfarb and Claire Potter, series editors

Before and beyond the tragic events of August 11 and 12, 2017, the town of Charlottesville, Virginia has been best known as the home of the University of Virginia. Founded by Thomas Jefferson in 1819, the university is a UNESCO World Heritage site that possesses some noteworthy artifacts: Moses Ezekiels 1907 statue of Homer; a section of the Berlin wall with murals by Dennis Kaun; and the Rotunda, the architectural apex of the universitys grounds, designed by the founding father himself. A history of the commitment to classical ideas, political engagement, and civic duty is coded into its very landscape. It is known as a public ivy, a school whose prestige and renown rival the private ivy league, and its esteemed faculty have included philosopher Richard Rorty, Poet Laureate Rita Dove, and astronaut Kathryn Thornton. Charlottesville, in a word, has been to the world a veritable leader in academic pursuits, its community and its campus embodying the highest order of strength of the intellectual spirit.

But on the evening of August 11, Charlottesville came to bear the symbols of an altogether different spirit. White supremacists, in a rally dubbed Unite the Right, marched in protest of the removal of a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee from Emancipation Park, just steps away from the University of Virginia. This removal, a gesture that many municipalities across the country have made towards a more honest recognition of the power of symbols within our nations troubled past, was especially hard-fought in Charlottesville, where the community has been grappling with Jeffersons own fraught relationship with the institution of slavery and the democratic ideals of his legacy (indeed, what the university and white supremacists have in common is a shared reverence for Jefferson, the latter for his lifelong perpetuation of the lie of biological race, and the former despite it).

Such a reckoning with our history has concerned those among us who consider themselves maligned in the age of political correctness, identity politics, and globalization. The forgotten men made themselves known, illuminating their faces by the light of torches, and brought the rest of the country to recognize their insecurity and their rage. As a culture, we are already inclined to obsess over these displays of aggression, but the audacity of the protesters to stake the claim they did made our captivation absolute. Many of us watched in horror. Comparisons were made to Nazi gatherings, and their proclamations (Jews will not replace us; white lives matter) affirmed the motivations and disturbing intent of their action.

The violence, including rioting, beatings, and a fatality, took place within a larger mobilization of white nationalism since the rise of Donald Trump. White supremacists have made themselves more visible by the hospitality of the presidents own racist views. Since his election, white supremacist rallies, conferences, and online communities have become more prevalent, and Charlottesville has been their most arresting yet. Photos of the event were shared widely and capture the intensity and spectacle of the gathering: black men lie on the ground, beaten with flag poles and two-by-fours; Confederate and Nazi flags wave above the faces of young white men, distraught and anguished, wearing the signature red hat of the Trump campaign; officers in riot gear press their shields against protesters shouting chants and racial slurs; the flailing bodies of counter-protesters hang delicately in the air as a vehicle rushes through the crowd. Horror led to heartbreak when we learned that this particular action resulted in the death of Heather Heyer. The shock of these images is enduring, and continues to haunt us. We could hardly say we are finished coping with this event. We have barely begun.

Hence, we consider the importance of this book to be evident in, firstly, its robust consideration of the context and implications of this event and, secondly, in its timeliness. It has been less than a year since this event took place, and we are still absorbed in the problems it posed: how do we cope with the political culture that has bred these fraught conditions? How did this despairing ideology proliferate so assiduously? How deep are its roots and to where do they lead? We still seem to be pouring over the statements our political leaders have made, as when the president condemned the violence on many sides. However, our care to do so is not because such responses offend our delicate political sensibilities. Rather, the Unite the Right rally is the consummation of a long history of the systemic oppression of black and brown people; it is the resurgence of a form of hate and violence that finds its precursors in lynchings and in the public burning of crosses. Still, we must acknowledge, it was not a simple reenactment. It is a present day problem and it demands a present day solution.

Next page