The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

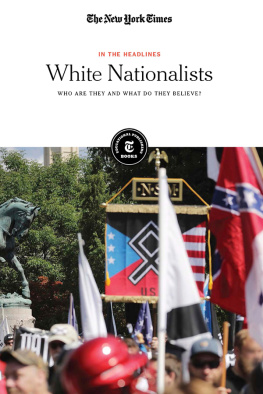

It made me very sad to see what happened in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017 when a thousand white nationalists and Ku Klux Klan followers showed up in broad daylight to preach violence and hate. I have been working against hate and resisting violence for more than half a century, and I thought we had come much farther as a people, as a nation. To me, August 12, 2017, was a very dark hour, a dark period for America. It hurt me to see so many people engaging in this type of madness.

The madness continued when the president of the United States stepped in front of the microphones that dark day and said he was condemning the tragic events of Charlottesville as an egregious display of hatred, bigotry, and violence on many sides, on many sides. That was very surprising to me, that any person in a position of leadership would equate the actions of violent white nationalists with those of peaceful protesters. People came to Charlottesville from all over the country preaching hate, division, and separation, and were met by a principled stand of locals who turned out to protest hate, often linking arms in nonviolent protest. That reminded me of the way my brothers and sisters and I had linked arms in Selma, Alabama, in 1965 and tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, named for a Confederate general, and were beaten, tear-gassed, trampled by horses, and left bloody.

I always believe in hope, and finally, on the dark day of the Charlottesville tragedy in August 2017, I had cause for hope. My heart lifted that day when at last someone spoke the words that needed to be spoken. Someone stood up and showed the leadership that the people of Charlottesville, the people of the entire nation, required in that dark hour to begin to steer toward the light. My friend Governor Terry McAuliffe was strong and clear in his condemnation of hate and racism.

To all the white supremacists and the Nazis who came into Charlottesville today, our message is plain and simple: Go home. You are not wanted in this great commonwealth. Shame on you, the governor said that day. You came here today to hurt people and you did hurt people. But my message is clear: We are stronger than you. You have made our commonwealth stronger. You will not succeed. There is no place for you here, there is no place for you in America.

Governor McAuliffe spoke the truth that day. He came across with conviction. Anyone listening could see he was speaking from the heart, angry and sad but filled with a sense of purpose.

I cried when I heard your speech, I told the governor the following Monday when I called him to thank him for his leadership. That was one of the great speeches Ive ever heard in my life.

Thank you, Congressman, he said. Coming from you, thats an incredible compliment.

Terry McAuliffe is not one to be at a loss for words, but that compliment left him momentarily speechless. Its true, Ive had the privilege to hear many great speeches in my lifetime, most especially during the March on Washington in August 1963 that I helped organize. I was one of ten speakers that day standing near the Lincoln Memorial, the last of whom was my friend, the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr., who that day delivered his timeless I Have a Dream speech.

Charlottesville chilled me to my bones because I had honestly believed we had come far enough as a country not to have to witness such naked hatred and racism on such a scale in broad daylight again. We always knew our struggle against hatred and racism would be a long one. We have lost so many brothers and sisters along the way. Im the only speaker from the March on Washington in August 1963 who is still alive. We must honor the memory of those we have lost by remembering. Its a constant struggle. We can never rest. We can never be weary, but must continue always to find a way to get in the way of racism and hatred.

Earlier this year, I visited the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, the church where four girls were killed by Ku Klux Klan domestic terrorists on a Sunday morning, September 15, 1963. Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, and Carole Robertson were each fourteen years old, and Carol Denise McNair was just eleven. When I visited the church, a group of high school students presented a play telling the story of what happened in 1963, and how it happened, both for members of Congress and for young people. I wish every American could see and witness this play. Were going to try to bring it to Washington, maybe on Capitol Hill, or the Kennedy Center. These young people were black, they were white, they were Latino, they were Asian American, and their play made us cry and it made us laugh. Thats progress.

Over the years, I have often been subjected to physical harm, and I bear the scars of the struggle, a small price to pay for playing my part to march us forward toward progress and understanding. Nashville was the first major city in the South to desegregate lunch counters and movie theaters, and in Nashville we learned the philosophy and the discipline of nonviolence from Jim Lawson, who had traveled to India as a Methodist minister and studied the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi. As I wrote in my memoir, Walking With the Wind: I couldnt have found a better teacher than Jim Lawson. There was something of a mystic about him, something holy, so gathered, about his manner, the way he had of leaning back in his chair and listening, really listening. We discussed and debated every aspect of Gandhis principles, from his concept of ahimsathe Hindu idea of nonviolent passive resistanceto satyagrahaliterally, steadfastness in truth, a grounding foundation of nonviolent civil disobedience, of active pacifism.

In 1961, the same year Barack Obama was born, black and white people could not board a Greyhound bus and be seated together. We used the principles of nonviolent civil disobedience Jim had taught us that year to work for change through the Freedom Rides, which I planned as an organizer of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. It was black and white together on long bus rides into the South, no matter the consequences. At a stop in Rock Hill, South Carolina, I tried to enter a so-called white waiting room and was attacked by members of the KKK, beaten, and left in a pool of blood.

Remarkably, a man named Elwin Wilson, one of the Klansmen who attacked me that day in South Carolina, visited me in my Capitol Hill office in 2009, along with his son.

Mr. Lewis, Im one of the people that beat you, he told me. I want to apologize. Will you forgive me?

Elwin Wilson and his son were both in tears.

I forgive you, I told the man.

You always like to think that weve come a distance and made progress as a nation, which was how I felt when a former KKK member like Elwin Wilson would pay me a visit in the United States Capitol to offer a heartfelt apology in the presence of his son. Then to have people come along to attempt to destroy that sense of progress, that sense of hope, the way they did in Charlottesville with a return of the KKK; it showed me, as it showed the entire country, how very long a way we still have to go.