Old Age in Australia

Old Age in Australia

A History

Pat Jalland

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

1115 Argyle Place South, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

mup-info@unimelb.edu.au

www.mup.com.au

First published 2015

Text Pat Jalland, 2015

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2015

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Typeset by J&M Typesetting

Printed in Australia by OPUS Group

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Jalland, Patricia, author.

Old age in Australia/Professor Pat Jalland.

9780522867060 (paperback)

9780522867077 (ebook)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Older peopleAustraliaHistory.

Older peopleCareAustraliaHistory.

Older peopleEconomic conditionsHistory.

Older peopleSocial conditionsHistory.

Nursing homesAustraliaHistory.

RetirementAustraliaHistory.

305.260994

Contents

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the Australian Research Council for a three year Discovery Grant which provided essential funding for this project on the history of old age in Australia. My thanks also go to Russell Doust, Karen Fox and Ann Hone for their valuable contributions as research assistants at different stages. Karen Smith and Akita Hodgson did a splendid job of converting my manuscript drafts into electronic form, with remarkable speed, accuracy and good humour.

I owe a special debt of gratitude to Joy Damousi, as Editor of the Melbourne University Press Academic History series, for her enthusiastic encouragement and thoughtful suggestions; and to John Hooper, for his wise advice and practical support from the outset. Pat Thane contributed invaluable ideas in the early stages of this project. Jim Hammerton, Di Langmore, Barry Higman, Nicholas Brown, Frank Bongiorno, Geoffrey Bolton, Ann Hone, Karen Fox and Jenny Harrison also gave very helpful comments on various chapters.

Permissions for quotations from manuscript collections have kindly been granted by the National Library of Australia (the Dame Mary Gilmore Diaries and the Edna Ryan Papers), by the State Library of Victoria (the McCrae papers), and by the Citizens Welfare Society of Victoria (formerly the Charity Organisation Society) for brief quotations from their files. Many thanks go to the staff of the National Library of Australia, the State Libraries of NSW and Victoria, and the J.S. Battye Library of West Australian History, State Library of Western Australia. My apologies to any copyright owners I have been unable to identify or locate.

Melbourne University Press staff have been very helpful throughout, especially Cathy Smith and Sally Heath; and my copy editor Penelope White. I am very grateful to Richard McGregor for his work on the index.

Introduction

This book explores the history of older people in Australia during the century from 1880 to 1980. It aims to fill a remarkable gap in Australian historiography, in a relatively neglected field of increasing social, cultural and economic significance. The age at which old age commences for individuals varies greatly with time, heredity, class, gender, health and living standards. In the course of the century from 1880 to 1980 life expectancy increased dramatically in Australia, as did the relative proportion of the elderly. People were seen to be aged considerably later in life by the twentieth century, and were more visible as well as more active. Despite such large variation over time, official sources have often tended to follow the Commonwealth 1908 Invalid and Old Age Pensions Act in adopting a definition of old age as sixty years of age for women and sixty-five for men, however inappropriate in the earlier decades.

Since 1911 unprecedented demographic change has transformed experiences of ageing dramatically, altering our assumptions about ageing in Australia. Demographers have estimated that in 1861 only 0.9 per cent of the population was aged over 65, rising to 2.4 per cent in 1881, 4.3 per cent in 1911, 8 per cent in 1947, 9.8 per cent in 1981, and 14 per cent in 2011. Thus the percentage of people over sixty-five more than doubled between 1911 and 1981, and it is An understanding of the history of older people in the century before 1980 is essential context for the current debate about the implications of ageing in the future.

In the nineteenth century there were relatively few elderly people in Australia, but by 1881 the proportion of the population aged sixty-five and over had more than doubled in twenty years. The 1880s are thus a reasonable starting point for this book. Further, the late 1970s and early 1980s represented a watershed in the history of the elderly in Australia and so I have used 1980 as an end date. The demographic transition to a higher proportion of older people was significant: at approximately 10 per cent of the population in 1981, with massive reductions in mortality and birth rates over the century which transformed the populations age structure. Indeed by the 1980s there were fears of an imminent ageing crisis which presented a significant social and political challenge.

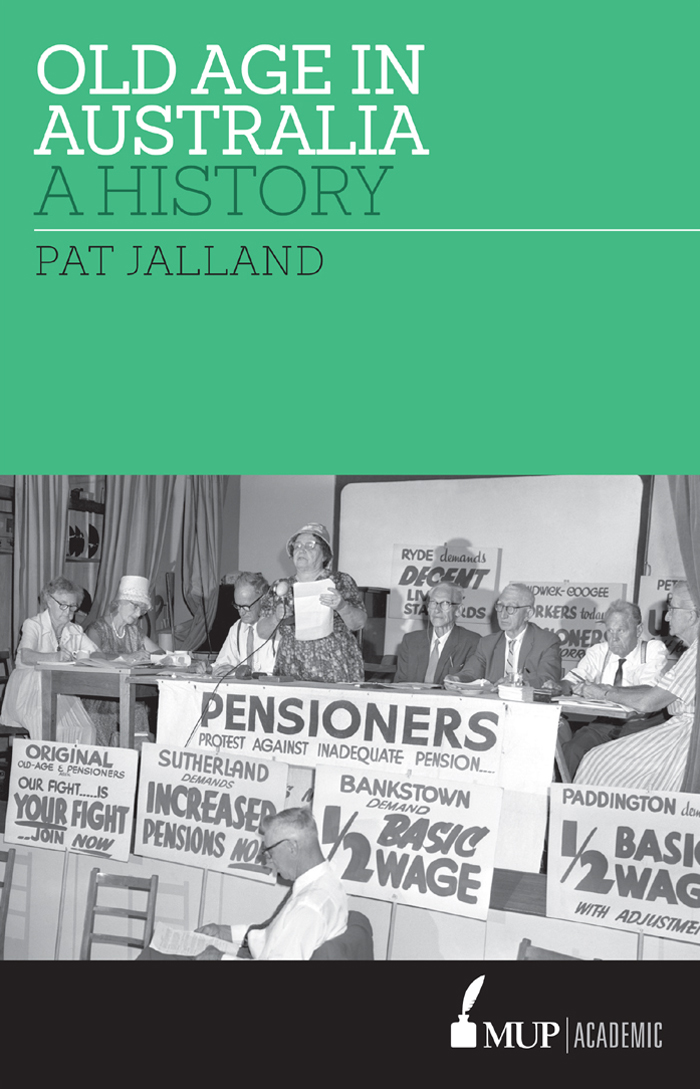

There is a major turning point in the history of old age in Australia in the later 1940s. The elderly population had been seriously neglected during the preceding two world wars and the intervening great depression. The only important federal reform for older people in half a century was the introduction of old age pensions in 1908. The limited number who benefited received a means-tested pension worth only a quarter of the basic wage. The elderly poor suffered abject poverty in rented rooms in inner city slums during the economic depressions of the 1890s and 1930s. Those who succeeded in gaining entry to the overcrowded benevolent asylums were separated from spouses and lived in often appalling conditions. Plans to modernise housing and asylums were postponed indefinitely. Although the federal government introduced a welfare state during the Second World War, there was little immediate benefit for older people, though indexation of pensions, long postponed, was at last introduced.

However, from the later 1940s there was belated consideration of the needs of the elderly, who were increasing in numbers and longevity. This was a significant turning point, led by the state of Victoria and more slowly by NSW. Philanthropists, journalists, clergy and compassionate citizens called for better conditions for the Despite extreme reluctance to intervene, the federal government belatedly responded in 1954 with the Aged Persons Homes Actonly the second federal government initiative for the elderly in 75 years. A major problem throughout this time was the arbitrary division of responsibilities between state and federal governments in key policy areas such as geriatric medicine, nursing homes, and home and community care. The consequences were detrimental, stimulating the phenomenal growth of nursing homes which were condemned by many as offering inferior care. But despite slow and sometimes haphazard progress, conditions and life experiences for many older people gradually improved between 1950 and 1980.