and for Morton L. Janklow,

my friend of more than four decades,

for his enthusiasm and our shared

love of history

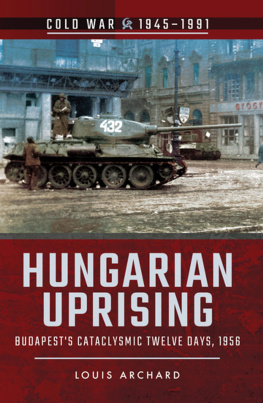

N othing presents more difficulties than writing an objective account of a great event in which one has participated oneself. Being objective about the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 is hard enough to begin withit is a kind of modern David and Goliath story, except that Goliath wonbut harder still for somebody who participated in it, like myself, and who was present at some of the major moments. The abb Sieys, when asked what he did during the French Revolution, replied, Je lai survcu (I survived it). I suppose I can, at the very least, make the same claim, but I also witnessed demonstrations of almost unbelievable courage, of shameless political betrayal, and of the kind of unrestrained military brute force and violence against civilians of which the twentieth century was so full, and which do not seem to have ended so far in the early years of the twenty-first.

Although there is no doubt that the events of October 1956 constituted a revolution, they swiftly became something else: a war.

The revolution was spontaneous, popular, and embraced every segment of society, including many members of the Hungarian communist party. It was a revolution against tyrannyagainst a singularly brutal and despotic single-party government that punished even the mildest dissent with extreme cruelty, including torture and death; that methodically stifled every form of self-expression and suppressed every individual impulse; and that was more Stalinist than Stalin himself had been.

It was also a revolution against eleven years of alien, heavy-handed, unyielding Russian domination and occupation. The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 swept away the communist partys control over every aspect of Hungarian life, and for a time forced the army of the Soviet Union to retreat before an angry armed body of Freedom Fighters, as they came to be known, consisting of workers, students, Hungarian army personnel, and ordinary civiliansmen, women, and children. At that point the Soviet Union launched a full-scale war against the Hungarian people, suppressed the revolution, and handed the country back to the hard-core Hungarian communist bureaucrats and their feared and hated security service.

Fifty years after the revolution, we are living in a very different world, one in which Hungary is a prosperous member of the European Union and of NATO; in which the Soviet Union has ceased to exist; and in which communism is virtually extinct except in China and Cuba. It is therefore important to remind ourselves of these eventsfor without the bravery of the men and women who fought in 1956, we might today still be living in the world of the cold war, of monolithic communism in eastern Europe, and of nuclear stalemate.

I hesitated for some time before deciding to include myself in this account of the revolution, but it seemed to me that many of these events benefit from being described by an eyewitness. I have tried to strike a balance between history and memoir, and have not tried to write a first-person account, since there were of course many things I did not see or participate in, and since my own experiences in the streets of Budapest in 1956 were primarily those of an observer. Many others took far greater risks than I did, and it is in their memory that I have written this book.

Throughout, I have tried to set down as accurately as I can what took place and why without sensationalism. In the days while I was in Budapest many things happened of a personal nature which I have not described herethis book is about the Hungarians and their revolution, not about me.

I am a camera, Christopher Isherwood wrote of his presence in Berlin in the years just before the Nazis came to power, with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking. Some day, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed.

So it was, and is, for me. I was a camera. I have recorded certain scenes as they were, fixed in my memory, like the black-and-white images of a war photographer, to give the reader an impression of what it was like to be in the middle of a revolution, and to show just what it is like to be on the spot when history and politics take to the streets.

But before one can explain the revolution, one must first explain what the cold war was like, in the days when the Iron Curtain was real, and still freshly built, dividing Europe in two as if it had been cut by a knife.

F ew things stand out less clearly at the time than a turning point in history, at any rate when one is living through it. As a rule it is only in retrospect that an event can be seen clearly as a turning point. Historians write as if they were looking at the past in the rearview mirror of a moving car; and, of course, picking the turning points of history is something of a specialty for many historiansin some cases, the more obscure, the better. Turning points, however, are much harder to recognize as they occur, when one is looking ahead through the windshield.

To take an example, we now recognize that the Battle of Britain was a turning point in World War IIfewer than 2,000 young fighter pilots of the Royal Air Force handed Hitler his first defeat, and ensured that whatever else was going to happen in 1940, Great Britain would not be invadedbut those who lived through the Battle of Britain day by day did not perceive it as a decisive, clear-cut event. The fighter pilots were too exhausted and battle-weary to care; and the public, while buoyed by the victories of the R.A.F. in the sky over southern England, was still struggling to come to grips with the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk and the collapse of France, and would soon be plunged into the first stages of what later came to be known as the blitz. Those whoas childrensaw the white contrails of the aircraft swirling overhead in the blue summer sky, or watched the shiny brass cartridge cases come tumbling down by the thousands, had no sense of being witnesses to a turning point; nor did their elders. It was only much later that this turning point began to be perceived as one, and that Battle of Britain Day was added to the list of annual British patriotic celebrations.

In much the same way, the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, while it was clearly a major event, was not perceived as a turning point in history until much later, when the unexpected disintegration of the Soviet empire in eastern Europe, followed very shortly by the total collapse of the Soviet Union itself, could be traced back to the consequences of the uprising in the streets of Budapest.

The three weeks of the Hungarian Revolution ended, of course, in a victory for the Soviet Union, as everybody knows, but not since Pyrrhus himself has there been so Pyrrhic a victory. The Hungarians had chipped the first crack in the imposing facade of Stalinist communism and had exposed the Soviet Unions domination of eastern Europe for the brutal sham it was. For the first time, people in the Westeven those on the lefthad seen the true face of Soviet power, and it shocked them.