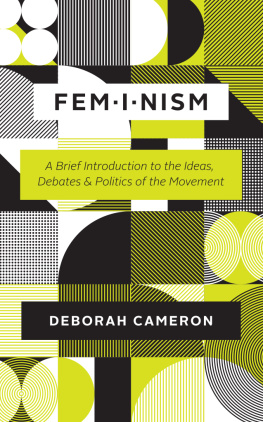

feminism

feminism

A Brief Introduction to the Ideas, Debates, and Politics of the Movement

DEBORAH CAMERON

The University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

2019 by Deborah Cameron

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2019

Printed in the United States of America

28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-62059-6 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-62062-6 (paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-62076-3 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226620763.001.0001

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Profile Books Ltd. Deborah Cameron 2018

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cameron, Deborah, 1958 author.

Title: Feminism : a brief introduction to the ideas, debates, and politics of the movement / Deborah Cameron.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018042176 | ISBN 9780226620596 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226620626 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780226620763 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: Feminism. | WomenSocial conditions.

Classification: LCC HQ1206 .C24 2019 | DDC 305.42dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018042176

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

I am grateful to all the feminists whose collective wisdom I have learned from over the years. Thanks to Marina Strinkovsky, Teresa Baron, and Nancy Hawker, and special thanks to my best critic, Meryl Altman.

We should all be feminists, declared the writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in her 2014 essay of that name.

Ambivalence about feminism is nothing new. In 1938 the British writer Dorothy L. Sayers gave a lecture to a womens society entitled Are Women Human? She began with this disclaimer: Your Secretary made the suggestion that she thought I must be interested in the feminist movement. I replieda little irritably, I am afraidthat I was not sure I wanted to identify myself, as the phrase goes, with feminism....

One answer might be that many women are wary of the word feminist, which has a long history of being used to disparage those so labeled as dour, unfeminine man-haters. But people who reject the label may nevertheless hold views that could be described as feminist. Some respondents to the 2014 poll mentioned above changed their initial, negative answer to the question, Do you consider yourself to be a feminist? after they were given a definition of a feminist as someone who believes in the social, political and economic equality of the sexes. Attitudes toward feminism tend to vary depending on what the term is being used to talk about. When people use the word feminism, they may be referring to any or all of the following things:

- An idea: as Marie Shear once put it, the radical notion that women are people.

- A collective political project: in the words of bell hooks, a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation and oppression.

- An intellectual framework: what the philosopher Nancy Hartsock described as a mode of analysis... a way of asking questions and searching for answers.

These different senses have different histories, and the way they fit together is complicated.

Feminism as an idea is much older than the political movement. The beginnings of political feminism are usually located in the late eighteenth century, but a tradition of writing in which women defended their sex against unjust vilification had existed for several centuries before that. The text that inaugurated this tradition was Christine de Pizans Book of the City of Ladies.Over the next four hundred years, other texts making similar arguments appeared in various parts of Europe. Their authors were relatively few in number, were not part of any collective movement, and did not call themselves feminists (that word did not come into use until the nineteenth century). But they clearly subscribed to the radical notion that women are people. Because their writings criticized the masculinist bias of what passed for knowledge about women in their time, they have sometimes been described as the first feminist theorists.

Dorothy Sayers also believed that women were people. A woman, she wrote, is just as much an ordinary human being as a man, with the same individual preferences, and with just as much right to the tastes and preferences of an individual. But that belief was what made Sayers reluctant to embrace feminism as an organized political movement. What is repugnant to every human being, she went on, is to be reckoned always as a member of a class and not as an individual person. This is the paradox at the heart of feminism in the second, political movement sense: to assert that they are people, just as men are, women must unite on the basis of being women. And since women are a very large, internally diverse group, it has always been difficult to unite them. Feminists may be united in their support for abstract ideals like freedom, equality, and justice, but they have rarely agreed about what those ideals mean in concrete reality. Feminism as a political movement has only ever commanded mass support when its goals were compatible with a range of beliefs and interests.

The movement for womens voting rights, which began in the nineteenth century and peaked in the early twentieth, is a case in point. Two of the central arguments deployed by suffrage campaigners rested on different, and theoretically opposed, beliefs about the nature and social Upper-class feminists sometimes argued that educated, property-owning women had a better claim to the vote than working-class men; socialists by contrast favored enfranchising all women, as well as all men, since that would strengthen the position of the working class as a whole. Many disparate interest groups stood to benefit from the extension of voting rights to women, and that was enough to bring them into an alliance. But once the vote had been won, womens differences reasserted themselves and solidarity gave way to conflict.

Feminisms story is not a linear narrative of continuous progress. The movement keeps being reinvented, partly to meet the challenges of new times, but also because of each new generations desire to differentiate itself from the one before. Holtbys complaint about womens repudiating the movement was made at a time when many younger women were questioning the need for feminism in a postsuffrage world: they saw both the cause and the women who had fought for it as relics of the past, with little relevance to their concerns. Something similar would happen fifty years later, as young women in the 1980s and 1990s rejected their mothers Womens Lib and media pundits proclaimed the advent of a postfeminist era. But those commentators spoke too soon: today the movement is on the march again (literally: witness the size and scale of the womens marches held to protest the inauguration of President Donald Trump in 2017), and according to polls like the one I mentioned earlier, the women currently most likely to identify themselves as feminists are those under the age of thirty. Their version of feminism has continuities with earlier versions, but it is also distinctive, reflecting the conditions and the ideas of its time.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).