Contents

Peter Clarke

HOPE AND GLORY

Britain 19002000

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Peter Clarke became Professor of Modern British History at Cambridge University in 1991 and Master of Trinity Hall, Cambridge, in 2000. His first book, Lancashire and the New Liberalism (Cambridge, 1971), was the source of much fruitful controversy about the decline of the Liberal Party. His developing interest in economic issues was signalled in The Keynesian Revolution in the Making, 192436 (Oxford, 1988). His book of essays, A Question of Leadership: Gladstone to Blair (1999) is also published by Penguin. He writes regularly for The Times Literary Supplement and the London Review of Books. He is a Fellow of the British Academy.

For Maria

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE PENGUIN HISTORY OF BRITAIN

GENERAL EDITOR: DAVID CANNADINE

HOPE AND GLORY: BRITAIN 19002000

Every chapter, almost every paragraph, is sustained by a depth and width of reading and knowledge on Clarkes part which gives the book its overall richness. It is especially rare to find a general study so precise and yet so interesting Peter Hennessy, The Times

A superb narrative Clarke has developed an enviably epigrammatic style, full of well-honed A. J. P. Taylor-like surprises a shining book bound to be the standard work on twentieth-century Britain for many years to come Ben Pimlott, New Statesman

Fascinating Clarke brings it off with brio and distinction. His judgments, and he does not fear to make them, are sound and balanced Raymond Carr, Spectator

This is potted history at its best: a balance between politics and social trends; a framework of facts, an entertaining edge of irreverent phrase; and all secured with a few tendentious opinions Roy Jenkins, Daily Telegraph, Books of the Year

Excellent A breakneck pace is maintained, cutting fiercely from dinner-jacketed BBC newsreaders to the fall of Lloyd Georges coalition, from cricket to the Edwardian fiscal crisis Philip Ziegler, Daily Telegraph

A remarkable achievement John Grigg, The Times, Books of the Year

Clarke writes with an understated sense of irony which makes this a most readable and entertaining book Three entire generations have lived through Clarkes history: their story has been told with admirable clarity, vigour and good humour Trevor Royle, Scotland on Sunday

THE PENGUIN HISTORY OF BRITAIN

Published or forthcoming

I: DAVID MATTINGLY Roman Britain: 100409

II: ROBIN FLEMING Anglo-Saxon Britain: 4101066

III: DAVID CARPENTER Britain 10661314

IV: MIRI RUBIN Britain 13071485

V: SUSAN BRIGDEN New Worlds, Lost Worlds: Britain 14851603

VI: MARK KISHLANSKY A Monarchy Transformed: Britain 16031714

VII: LINDA COLLEY A Wealth of Nations? Britain 17071815

VIII: DAVID CANNADINE The Contradiction of Progress: Britain 18001906

IX: PETER CLARKE Hope and Glory: Britain 19002000

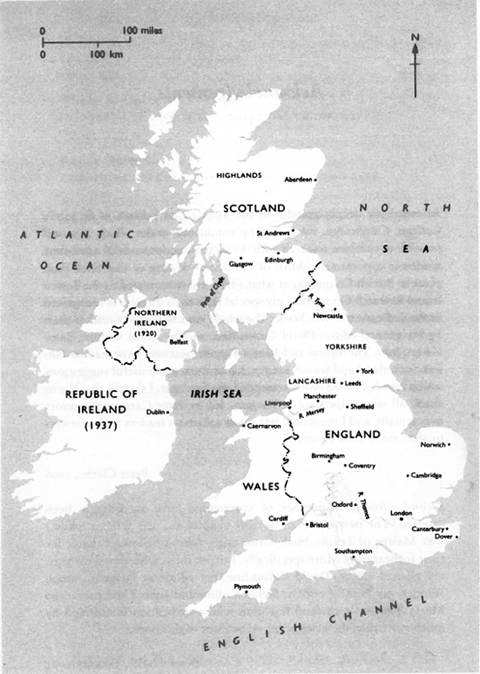

Map 1 Great Britain and Northern Ireland

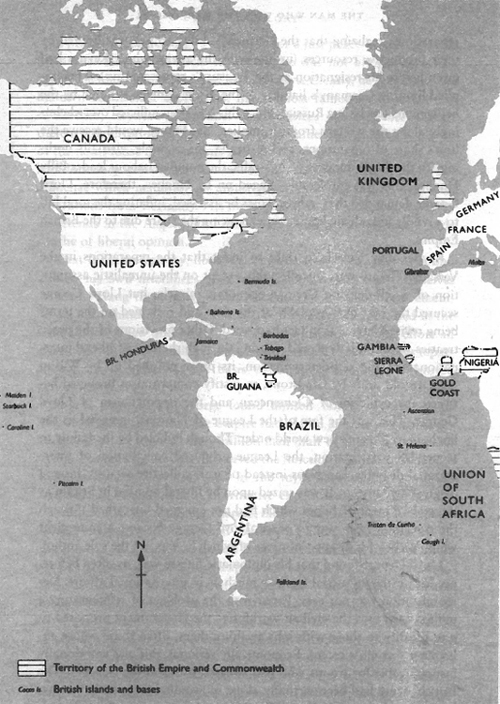

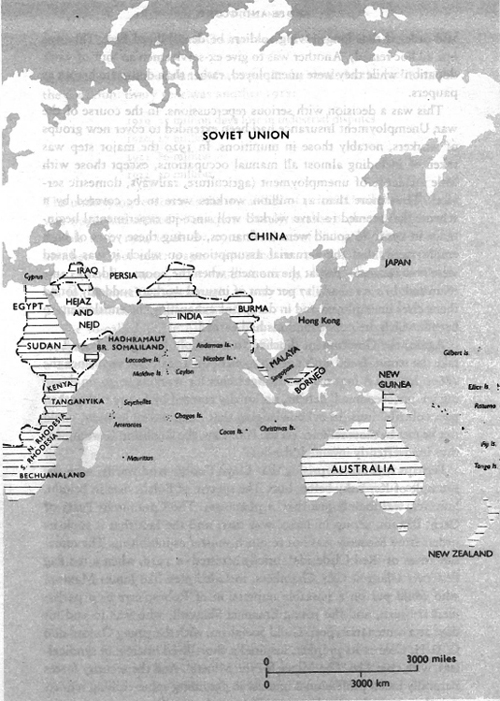

Map 2 The British Empire in 1920 (After .. Lloyd, The British Empire, 15581983, Oxford, 1984)

Prologue

One traditional motive for looking at history, especially national history, has been for inspiration and encouragement. Shakespeare wrote his histories, of course, establishing the image of this England as a sceptred isle, and Milton introduced a heightened notion of the special relationship between God and his Englishmen. Such phrases, fine coinage when newly minted, passed into the currency of later generations as clichs. Yet 1940 showed that this heroic register still found a resonance. Winston Churchill was able to tap a providential sense that the British Empire and its Commonwealth, standing together but standing alone, were capable of saving themselves and thereby the world at an apocalyptic moment. Churchills gift was to make this finest hour into history while its minutes were actually ticking away. With his aristocratic pedigree and American mother, Churchill was hardly the typical British citizen. Nor, it might be said, was the left-wing writer George Orwell, whose gut reaction in 1940 ranged him, for the moment, firmly behind Churchills position. Orwells famous metaphor of his country, as a family with the wrong members in control, nonetheless depended on the binding ties of its private language and its common memories.

One difficulty in this nationalist reading of our island story is that it begs the question of what or who constitutes the nation. In 1900 the United Kingdom essentially comprised two large north Atlantic islands. In Great Britain, England took up just over half of the land area, Wales and Scotland the rest. In what Shaw called John Bulls Other Island, the predominantly Catholic population, concentrated in the southern counties, had a well-developed sense of their own Irish national identity that disclosed a clear political rift with the mainly Protestant defenders of the Union, concentrated in a number of northern counties. This was already a disunited kingdom, and was to become more so, notably when Ireland established its own independence as a republic, though with a continuing dispute about the border, which continued to define Northern Ireland as part of the Union. The history of the twentieth century has surely shown that partition was no neat and permanent, still less preordained, solution to the Irish question; and that manifestations of national identity in Wales and Scotland the one more cultural, the other more political echo more strident and bloody attempts to reassert or reinvent diverse nationalisms worldwide.

British history has generally dealt with nationalism by ignoring it. Churchill and Orwell slipped into a well-established convention of illicitly, implicitly conscripting all Britons into the pageant of English history, with a few tartan-clad spear-carriers and Celtic bystanders, presumed to be muttering the Welsh for rhubarb. It is a mark of changing times that the Penguin History of Britain replaces a series simply called the Pelican History of England. I do not claim in this volume to have given wholly adequate attention to the history of Ireland as a part of the United Kingdom in the first quarter of the century; or to Northern Ireland since then, or to Scotland and Wales throughout the period. But this volume does not, I trust, show itself oblivious of their very existence and it acknowledges that the term Britons is problematic, even if it cannot fully explore the dimensions of the British problem. At any rate, English and British, England and Britain, have ceased to be acceptable synonyms.