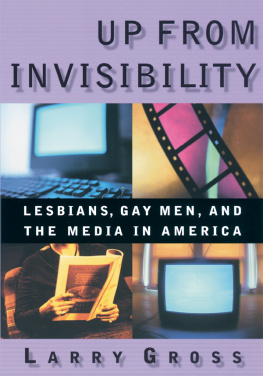

UP FROM INVISIBILITY

BETWEEN MEN ~ BETWEEN WOMEN

LESBIAN AND CAY STUDIES

LILLIAN FADERMAN AND LARRY CROSS, EDITORS

Up

from

Invisibility

LESBIANS, GAY MEN, AND THE MEDIA IN AMERICA

Larry Gross

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2001 Larry Gross

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-52932-7

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gross, Larry P.

Up from invisibility : lesbians, gay men, and the media in America / Larry Gross.

p. cm.(Between menbetween women)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0231119526 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 0231119534 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Mass media and gaysUnited States

I. Title. II. Series.

P94.5.G38 G76 2001

305.9'664'0973dc21 2001042140

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

BETWEEN MEN ~ BETWEEN WOMEN

LESBIAN AND GAY STUDIES

LILLIAN FADERMAN AND LARRY CROSS, EDITORS

Advisory Board of Editors

Claudia Card

Terry Castle

John DEmilio

Esther Newton

Anne Peplau

Eugene Rice

Kendall Thomas

Jeffrey Weeks

Between Men ~ Between Women is a forum for current lesbian and gay scholarship in the humanities and social sciences. The series includes both books that rest within specific traditional disciplines and are substantially about gay men, bisexuals, or lesbians and books that are interdisciplinary in ways that reveal new insights into gay, bisexual, or lesbian experience, transform traditional disciplinary methods in consequence of the perspectives that experience provides, or begin to establish lesbian and gay studies as a freestanding inquiry. Established to contribute to an increased understanding of lesbians, bisexuals, and gay men, the series also aims to provide through that understanding a wider comprehension of culture in general.

This book is dedicated to Rita Addessa, whose untiring efforts will ensure a better world for the children of a future age

CONTENTS

No one looking at the young woman who walked into a lesbian bar in Los Angeles in the summer of 1947 would have suspected they were witnessing a milestone in American social history. A 26-year-old secretary who called herself Lisa Ben (an anagram of lesbian) was distributing copies of a new publication she had created called Vice Versabecause in those days our kind of life was considered a vice. The magazine consisted of only fifteen type-written pages, but it signaled the first stirrings of the modern gay rights movement in the United States.

Fifty years later, in the summer of 1997, a 17-year-old high school senior in Wisconsin responded to Ellen DeGeneress coming out on the cover of Time, the Oprah Winfrey Show, and nearly every other media forum by writing a column for Oasis, an online magazine for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth, in which she proclaimed her intention of living her life honestly, because I have nothing to hide.

Between these two moments in modern American history lies a chasm bridged by transformations in culture, politics, and media that no one in 1947 could have foreseen.

This is a book about the emergence of lesbian and gay Americans from the shadows of invisibility and their entrance onto the playing fields of politics and culture. It is also a book about the role of media in bringing together a self-conscious community that was able to organize a movement and demand change; and about the role of media in portraying gay people to the majority and to gay people themselves, in ways that perpetuated harmful stereotypes and, eventually, also in ways that began to reverse some of that harm. While the stories told in this book constitute a chronology, because I am following several threads the narrative circles back occasionally to pick up another strand in the interwoven stories of media and movements, politics and performers. The primary focus of this narrative is on journalism, both minority and mainstream, and the two widest channels of American popular culture, movies and television. However, as we approach the present, the focus will broaden to encompass a wider range of media and genres, including pop music, sports, comics, pornography, and the Internet.

A half century ago homosexuality was still the love that dared not speak its name: it was a crime throughout the United States (whereas today it is criminalized in eighteen states). In the fervor of the Cold War that gripped the country, homosexuals were targeted along with Communists. Newspapers and magazines referred to homosexuals only in the context of police arrests or political purges, as in a 1953 headline: State Department Fires 531 Perverts, Security Risks. Hollywood operated under the Motion Picture Production Code, which prohibited the presentation of explicitly lesbian or gay characters and ensured that any implied homosexual characters would be villains or victims. Television was the new kid on the block, just barely beginning its colonization of the nations living rooms. The emergence of a gay movement in the 1950s coincided with the societal transformations wrought by television and the increasing centrality of communications technologies in American society.

The lesbian and gay liberation movement that seemed to appear spontaneously across the country shortly after the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City was in fact the result of a process begun in a post-World War II urban gay world that was largely invisible to heterosexual society, and whose growing self-consciousness in the decades prior to Stonewall can be traced in large part to the lesbian and gay press of which Lisa Ben was a pioneer.

Throughout the 1950s and into the 1960s, the homophile movement (as it was then called) expanded and deepened the self-awareness of lesbian and gay people as a distinct, self-conscious, and embattled minority. The movement was born behind a veil of pseudonyms and secrecy at the height of the Cold War, and its members, defined as criminal, mentally ill, and immoral, attempted to effect social change by persuading experts to speak in their behalf. With the advent of television, several brave activists appeared on the new medium, using pseudonyms but this did not protect them from being recognized and promptly fired.

By the early 1960s, movement leaders emerged who were inspired by the civil rights movement to proclaim that Gay Is Good! They began taking their struggle to the streets, demonstrating in front of government buildings, demanding an end to laws that criminalized gay people and promoted discrimination and harassment.

The Stonewall riots in June 1969 harvested a crop planted by a decade of political and social turmoil. The new movement was founded on the importance of coming out as a public as well as an individual act. The open avowal of ones sexual identity, whether at work, at school, at home, or before television cameras, symbolized shedding the self-hatred that gay men and women had internalized. To come out of the closet quintessentially expressed the fusion of the personal and the political that the radicalism of the late 1960s exalted.

Among the early targets of the newly militant gay liberation movement were the images presented in the media: Hollywood films and television programs, as well as the stories reportedor ignoredby the news media. From the earliest post-Stonewall days, mainstream news media and Hollywoods dreamor nightmarefactories were never far from the center of movement attention. While activists chalked up steady but modest victoriesmodifying a dramatic plot to dilute a stereotypic portrayal, persuading an editor to avoid the term pervert or adopt the term gayit was still left to the struggling lesbian and gay press to keep a growing community informed about the matters of greatest concern to its fate. The importance of the gay press was evident as the backlash against the early gains of gay liberation took shape in the mid-1970s.