A Prehistory of the Cloud

A Prehistory of the Cloud

Tung-Hui Hu

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2015 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please email special_sales@mitpress.mit.edu.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-262-02951-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-262-33010-7 (retail e-book)

1. Computer networksHistoryPopular works. 2. InternetSocial aspectsPopular works. I. Title.

TK5105.5.H79 2015

004.6dc23

2015001899

EPUB Version 1.0

Acknowledgments

Portions of this book were written while at the Michigan Society of Fellows and at the Stanford Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. Many units of the University of Michigan provided research funding and advice, including the Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies, the Department of English, the University of Michigan Library, the Office of Research, and the College of Letters, Sciences, and the Arts. I thank these organizations for their support.

This book is for my correspondents: Megan Ankerson, Finn Brunton, John Cheney-Lippold, Victor Mendoza, and Lisa Nakamura. Thanks to Katy Peplin, whose work as a research assistant helped take this project in new directions. Ben Lemperts editorial advice has been indispensible and transformative. Karen Beckman, Linda Williams, Kaja Silverman, and Anne Wagner provided the intellectual scaffolding for this studyhopefully invisible to the reader, yet deeply felt nonetheless. Doug Sery, Susan Buckley, and Kathleen Caruso at the MIT Press brought this project to fruition. Im grateful to the generous colleagues who read and commented on drafts of this book, including Sara Blair, Jonathan Freedman, Ilana Gershon, Roger Grant, Jeffrey Todd Knight, Petra Kuppers, Erica Levin, Kris Paulsen, Dan Rosenberg, Polly Rosenwaike, Ruby Tapia, Terri Tinkle, Damon Young, and Genevieve Yue; thank you. Last, for being there through the ends, and thus the beginnings: Elizabeth Bruch.

Introduction

Like the inaudible hum of the electrical grid at 60 hertz, the cloud is silent, in the background, and almost unnoticeable. As a piece of information flows through the cloudprovisionally defined, a system of networks that pools computing powerit is designed to get to its destination with five-nines reliability, so that if one hard drive or piece of wire fails en route, another one takes its place, 99.999 percent of the time. Because of its reliability and ubiquity, the cloud is a particularly mute piece of infrastructure. It is just there, atmospheric and part of the environment.

Until something goes wrong, that is. Until a dictator throws the Internet kill switch, or, more likely, a farmers backhoe accidentally hits fiber-optic cable. Until state-sponsored hackers launch a wave of attacks, or, more likely, an unanticipated leap year throws off the servers, as it did on February 29, 2011. Until a small business in Virginia makes a mistake, and accidentally directs the entire Internetyes, all of the Internetto send its data via Virginia, and, almost unbelievably, it does. Until Pakistan Telecom inadvertently claims the data bound for YouTube. A multi-billion-dollar industry that claims 99.999 percent reliability breaks far more often than youd think, because it sits on top of a few brittle fibers the width of a few hairs. The cloud is both an idea and a physical and material object, and the more one learns about it, the more one realizes just how fragile it is.

The gap between the physical reality of the cloud, and what we can see of it, between the idea of the cloud and the name that we give itcloudis a rich site for analysis. While consumers typically imagine the cloud as a new digital technology that arrived in 20102011, with the introduction of products such as iCloud or Amazon Cloud Player, perhaps the most surprising thing about the cloud is how old it is. AT&T launched the electronic skywaya series of microwave relay stationsin 1951, in conjunction with the first cross-country television network. And engineers at least as early as 1970 used the symbol of a cloud to represent any unspecifiable or unpredictable network, whether telephone network or Internet.

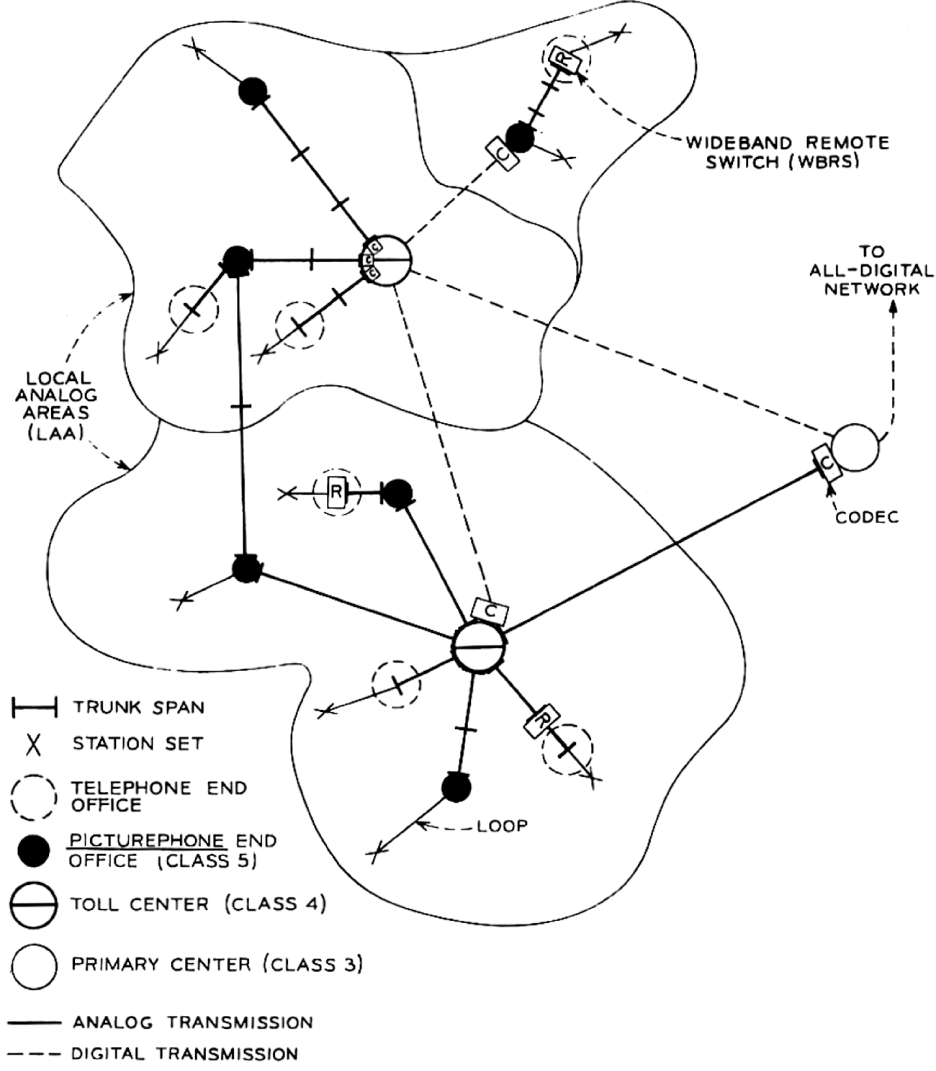

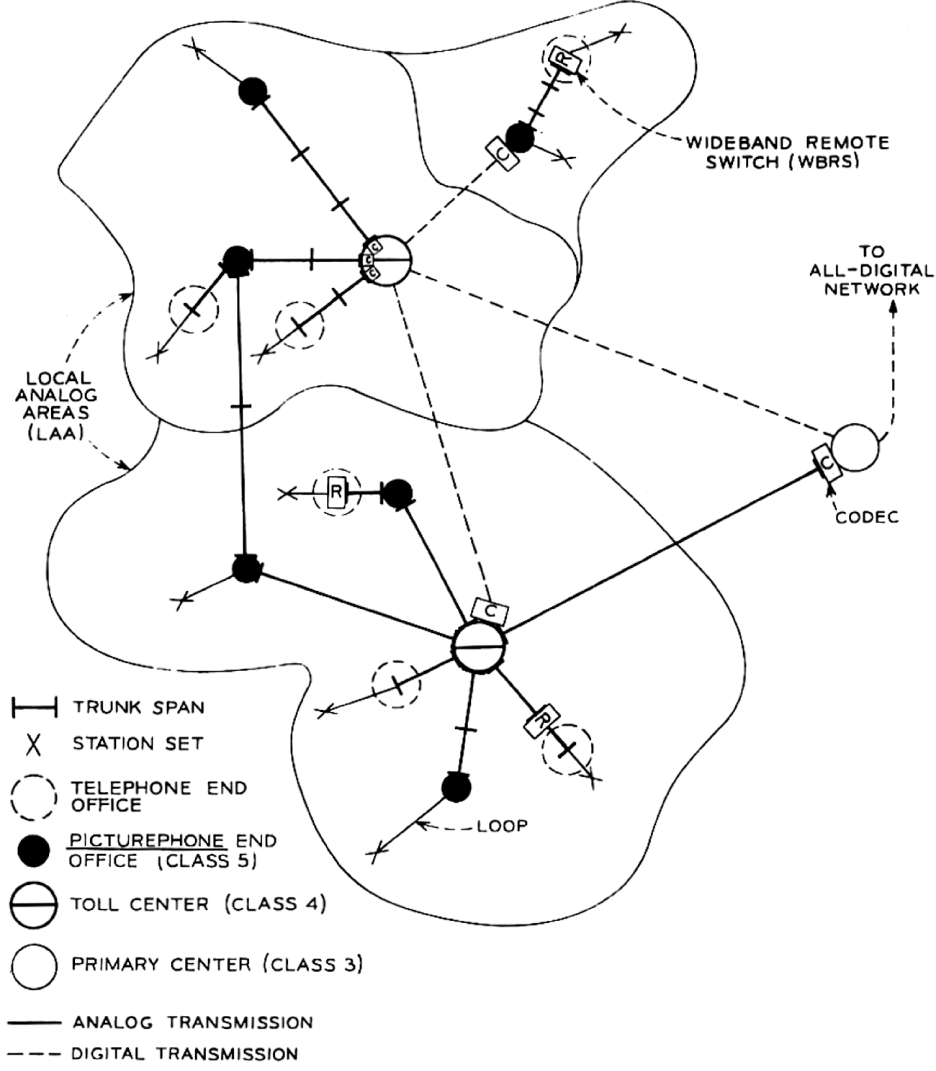

Figure I.1

Illustrative local area configurations. Source: Irwin Dorros, The Picturephone System: The Network, Bell System Technical Journal 50, no. 2 (February 1971): 232. 1971 The Bell System Technical Journal. Reprinted with permission.

What we learn from the diagram is simple: the clouds genesis was as a symbol. The cloud icon on a map allowed an administrator to situate a network he or she had direct knowledge ofthe computers in his or her office, for examplewithin the same epistemic space as something that constantly fluctuates and is impossible to know: the amorphous admixture of the telephone network, cable network, and the Internet. While the thing that moves through the sky is in fact a formation of water vapor, water crystal, and aerosols, we call it a cloud to give a constantly shifting thing a simpler and more abstract form. Something similar happens in the digital world. While the system of computer resources is comprised of millions of hard drives, servers, routers, fiber-optic cables, and networks, we call it the cloud: a single, virtual, object. To do so not only make things easier on users and computer programs, but also allows the whole system to withstand the loss of an individual part. (Most of the time, anyway.)

As a result, the cloud is the premier example of what computer scientists term virtualizationa technique for turning real things into logical objects, whether a physical network turned into a cloud-shaped icon, or a warehouse full of data storage servers turned into a cloud drive. But the gap between the real and the virtual betrays a number of less studied consequences, some of which are benign and some of which are not. Ones data trail grows with each website one visits and each packet one sends through the cloud. The results are used by both marketing companies trying to target an online ad for, say, auto insurance, and government agencies trying to target terrorists for extrajudicial killings. We tend to perceive the two kinds of targeting as separate because online privacy appears to be a born-digital problem that has little to do with geopolitics. That gap, then, is crucial. The word cloud speaks to the way we imagine data in the virtual economy traveling instantaneously through the air or skywayhere in California one moment, there in Japan the next. Yet this idea of a virtual economy also masks the slow movement of electronics that power the clouds data centers, and the workers who must unload this equipment at the docks. It also covers up the Third World workers who invisibly moderate the websites and forums of Web 2.0, such as Facebook, to produce the clean, well-tended communities that Western consumers expect to find. By producing a seemingly instant, unmediated relationship between user and website, our imagination of a virtual cloud displaces the infrastructure of labor within digital networks.