To Iain and our children

Contents

PART ONE

Trial and Errors

PART TWO

Intellectuals and Anti-intellectuals

PART THREE

Movements and Mystiques

PART FOUR

The End of the Affair

Illustrations

Every effort has been made to contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be happy to make good in future editions any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

Acknowledgements

Books that take long to write incur innumerable debts of gratitude. This work could not have been attempted without the prodigious efforts of Clara Lecadet and Annick Fenet, who laboured for months in archives in France transcribing documents of all kinds essential to my reinterpretation of the Dreyfus Affair. Although not professional historians (Clara is a psychologist and author, and Annick an art historian who specializes in antiquity), both brought an unparalleled commitment to a project that was not their own. At every step of the way, they offered their insights and corrected my errors. Their critical insights are everywhere in this book.

I have also had extraordinary help from colleagues on both sides of the Atlantic. Edward Berenson, Robert Gildea and Robert Nye, all senior French historians, read the work and offered suggestions on structure, argument and detail. My old friends and intellectual helpmates Lyndal Roper and Nick Stargardt read more than one draft and spent hours, over many years, talking about the book and thinking with me about method and approach. The History Department at the University of Wisconsin at Madison invited me to speak at the George Mosse Lectures in 2006, giving me an early opportunity to present my ideas to a wonderfully receptive audience. Dominique Kalifa at the Universit Paris 1 invited me to sit on the jury that examined Vincent Duclerts monumental thesis on the role of the savants in the Affair. Although Vincent and I approach the history of the Affair in very different ways, experts will know how indebted I am to his remarkable discoveries over the past two decades. Steven Englund generously allowed me to read parts of his unpublished manuscripts, while Bertrand Joly kindly provided me with a copy of his most recent, wonderful book on the right in France. Pre Charles Monsch once again provided obscure documents that enabled me to trace the details of personalities and events within the Assumptionist Order.

New College is a special place to work, and I am exceptionally lucky to have colleagues like David Parrott and Christopher Tyerman, who have been endlessly interested in a subject very far from their own area. Rene Williams spent literally hours worrying over the French translations with me, while Cecilia Mackay provided the images in this volume and provided advice on how best to integrate them into the text. The British Academy offered substantial support for research assistance, while the Leverhulme Foundation funded a years research leave that enabled me to finish the book. At Penguin Press, Simon Winders enthusiasm sustained me as the manuscript neared completion. Sara Bershtel and Grigory Tovbis at Metropolitan Books in New York were an exacting editorial team, whose meticulous commentary made me rethink the volumes structure. Donna Poppy did much more than copy-edit. At the very last stages she asked for important clarifications, made suggestions on narrative tone and caught many errors. Eric Christiansen, now retired from New College, generously offered to complete the index. Melanie Jackson in New York aided communication between the presses, while Gill Coleridge, my agent in London, always found time to advise, respond and solve problems; I am more grateful to her than I can say.

Iain Pears remains my greatest inspiration, perhaps because his love of history is even greater than my own. Only he knows how much he has done to keep me on track when exhaustion and moments of despondency threatened to take over. Our children, Michael and Alex, have surprised me by their unstinting interest in a story about prejudice and conspiracy that happily still baffles them. This book is for all three of them.

Preface

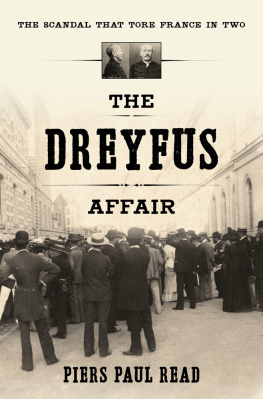

My first encounter with the Dreyfus Affair occurred sometime in my pre-adolescence while growing up outside Philadelphia. I remember my horror when told the story of the Jewish captain, wrongfully condemned for treason and then imprisoned on Devils Island. The history teacher related the tale of righteous Dreyfusards battling against iniquitous right-wing nationalists and anti-Semites; and he encouraged us to draw parallels between the struggle to free Dreyfus and the civil rights movement of the 1960s. In Hebrew school the story was couched in different terms but seemed to hold equal significance. Had not Theodor Herzl, the father of modern Zionism, clarified his views after reporting on the Affair for his Viennese newspaper? If France, the home of the Revolution, was susceptible to the basest anti-Semitism, was that not proof of the need for a Jewish homeland? For the rabbis who sought to maintain our Jewish identity in multi-cultural America, the Affair proved the pitfalls of assimilation.

As my career advanced, these earlier concerns completely drifted away from my work. A decade ago I wrote a history of the miracles and apparitions of Lourdes, the healing shrine in south-western France, and immersed myself in Marian piety, curative rituals and ecclesiastical history. While I enjoyed this work precisely because it appeared to take me into an utterly foreign world, the history of Lourdes brought me right back to the Affair. The Catholic faithful who journeyed to the shrine often detested the Republic and hated secularism; some of the gentle organizers of pilgrimage for the sick were also the most violent anti-Semites and most extreme anti-Dreyfusards. When in his 1894 novel Emile Zola characterized the miracles at the shrine as nothing more than the product of hysterical suggestion, Catholic activists pilloried him as a godless devil; both sides were ready to renew the battle when four years later Zola became Dreyfuss most famous champion.

When I began to look at the Affair, I had a feeling that I had something new to say, even though it was a subject that had already produced hundreds of historical works. Lourdes had made me realize that the political history of the right in the period was misjudged: anti-Dreyfusards were more than proto-Fascists, and the Affair was no dress-rehearsal for later inter-war developments. Reassessing right-wing personalities and ideologies required a greater appreciation of the unique context of the fin de sicle . Catholicism, science and the occult were all important ingredients in the powerful anti-Semitic cocktail, and only someone versed in these arcane debates could understand its peculiar power.

But my examination of the left was much more problematic. I have been studying France for over twenty years and have had a love affair with French culture. I have no doubt that this attraction was in part fostered by my fascination with the intellectuals, a term that acquired its mystique during the Affair. No other society in the West has given such a large and important role to thinkers and opinion-makers, an influence all the more beguiling because so many intellectuals held positions in French universities. They were extraordinary in the way they descended from their ivory towers to join the mle , and seemed to provide a model for rational engagement in politics.