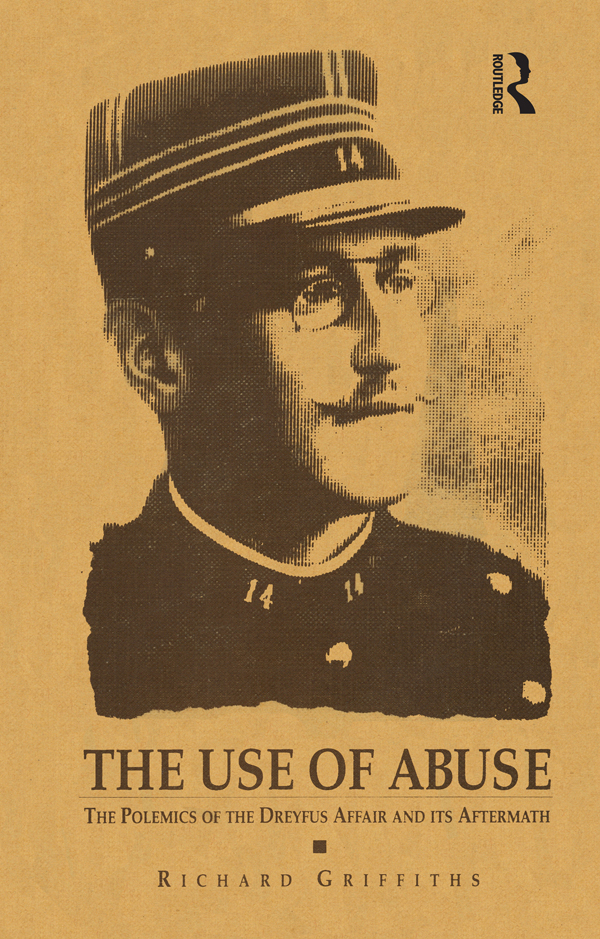

The Use of Abuse

In this book, which closely examines the techniques used by the polemists of the Dreyfus Affair, much is learned not only about the Affair itself, but also about the polemic of the age in which it was situated, and the interaction between writers and their public. The discourse within which peoples thoughts were imprisoned is seen not merely to have reflected events, but to have created them, in an increasingly vicious circle whereby the language of popular abuse, incorporated into the written polemic of the Press, produced simple but distorted ideas which in turn were fed back into the people. The ages complete lack of concern for the libel laws led to particularly vivid examples of the art. We are shown how authors shifts in vocabulary, and in stylistic techniques, unconsciously signal to us fundamental changes in their aims; and how, in the give-and-take of battle, words and concepts subtly changed their meaning, with certain abstract notions such as Truth and Justice becoming completely devalued.

Richard Griffiths is Professor of French at Kings College London.

First published 1991 by Berg Publishers

Published 2020 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

605 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Richard Griffiths 1991

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Griffiths, Richard.

The use of abuse the polemics of the Dreyfus affair and its aftermath /

Richard Griffiths

p. cm. (Berg French studies series)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-85496-626-9

1. Dreyfus, Alfred, 18691935. 2. FrancePolitics and

government18701940. 3. AntisemitismFranceHistory. 4. Authors,

FrenchPolitical activity. 5. Politics and literature-

-FranceHistory. 6. Polemics. I. Title. II. Series.

00354.G76 1989

944.081 2092dc20

89 - 7668

CIP

British Library Cataloging in Publication Data

Griffiths, Richard, 1935-

The use of abuse: the problems of the Dreyfus Affair and its aftermath.

1. French language. Grammar. Controversies

I. Title

ISBN 13: 978-0-8549-6626-4 (hbk)

Words do not merely reflect events; they often create them. Just as our perception of reality is shaped by the language that we use to describe it, so, more dynamically, that reality itself can be altered by changes in our forms of expression. As has rightly been said: Language makes or deconstructs our world, shapes our perception of what our world is. Historians of the French Revolution, realising this fact, have concentrated more and more, of recent years, on the Revolutionary discourse, and charted the way in which it influenced events. The Revolution is, however, merely one of the most obvious examples of a process which continually underlies political activity.

. Steven Blakemore, Burke and the Fall of Language: The French Revolution as Linguistic Event, Hanover and London, 1988, p. 105.

Not only words, but also the style in which those words are encased, can have this dynamic effect. The forms into which language is poured can constrain thought, to the extent that it is inevitably led in one direction rather than another. The most obvious examples of this lie in the great rhetorical disposition exercises and their heirs the formal treatises of the eighteenth century; but, less obviously, stylistic forms on a smaller scale continually have an influence upon the way we act and think.

The Dreyfus Affair presents us with a particularly rich field for a study of such trends. That an individual case of miscarriage of justice should have led to a political affair which violently divided the nation, not only for the few years involved, but also for subsequent generations, has of course always been explicable by the already divided state of the France in which it took place. But that division, and the discourse used by those involved in it, were inextricably intermingled. The polemic of late nineteenth-century France had certain characteristics which both reflected entrenched attitudes and created new tensions. Much of the swift development of the crisis of the Affair can directly be traced to the language and style used by its protagonists.

Many of the characteristics of that language and that style are, as we shall see, bound up in the development of the French popular press during the course of the nineteenth century. Other aspects reflect the violent events of that century, the many changes of regime, and the myths attached by the heirs of those regimes to their own specific forebears. Out of it all came a series ofclan languages, formed of rallying-cries and formalised insults, which not only simplified political debate, but also, once they had come into operation, predetermined the course of events.

Our study of this phenomenon will naturally, in part, be concerned with the general characteristics of polemic, in contrast with more reasoned argument; upon this basis, however, we will be looking more closely at the particular form which polemic took in this period of French political history, and at the effects of this development. The Affair represents the climax and the greatest testing-ground of certain polemical usages typical of the French nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

At the core of our investigations lies a stylistic examination of the actual words and phrases used. In some cases these words and phrases became devalued through over-use; in others the familiarity of stock phrases could lead, in the hands of accomplished polemists, to striking ironical effects. We can observe the writers expectations of their readers and perceive something of the nature of the audience that was being addressed; and, in some instances, we can detect changes in a writers attitudes, and in his aims, through an assessment of the degree to which these stylised techniques were incorporated into his writings at different points in time. All this is not merely of use in establishing certain constants in current polemical usage; it also, at times, helps to give us new insights into the often unconscious motives of individual writers.

A study such as this, therefore, can not only help us towards a general understanding of human political behaviour, but also provide new insights into the Dreyfus Affair itself.

In the area of language, two books, while dealing with later periods, have been of particular use to me because of the method they displayed. They are Francesco Siccardos close study of two words relating both to early twentieth-century Catholicism and to the French Right, Intgriste e Intgrisme: Stratograjia di due vocaboli francesi (Genova, 1979), and Dr Catherine Slaters brilliant study of the language of the First World War,