Introduction: Democracy without trust

This is a book about democracy. Notdemocracy as an ideal or as a set of institutions but democracy asa collective experience. It is, primarily, a book about the natureand sources of our present disappointment with democracy. Both as aconcept and as a reality, democracy is undergoing a profoundtransformation. The Woodstock-to-Wall-Street social and politicalrevolution of the 1970s and 1980s; the end of history revolutionsof 1989; the digital revolution of the 1990s; the demographicrevolution; and the political brain revolution that is unfolding infront of our eyes, brought by the new discoveries in the brainsciences and behaviorist economics, have made citizens freer thanever before. But these revolutions have simultaneously eroded thepower of the democratic voter. Our rights are no longer secured byour collective power as voters but are subject to the logic of thefinancial market and the existing constitutional arrangements.Voters can change governments, yet it is nearly impossible for themto change economic policies. The elites have broken free fromideological and national loyalties and have become global players,leaving society in the broken shell of the nation state. There hasbeen a profound decline of the publics trust in the performance ofpublic institutions. This mistrust is not an outcome of thedeterioration of public services. It is an outcome of the voterssense of their lost power in their disillusionment withdemocracy.

Some of the most insightful theorists of modern democracy including Pierre Rosanvallon in his brilliant book Counter Democracy insist that we arewrongly alarmed with the declining trust in the institutions ofrepresentative democracy. They say that mistrust is a criticalelement of the political system and that democracy is not so muchabout trust as about the organization of distrust. In short, welive in an age in which average citizens will be able toefficiently monitor the executive power and voters will be able tokick out the rascals in power, yet in which citizen-voters willalso have to concede that it is not up to them to decide in whatkind of society they will live.

Do you believe in such a democracy of mistrust? Can we enjoy ourrights without enjoying real political choice? I do not, and thisshort book is an attempt to explain why.

This book is not meant to be a polemic or problem-solvingmanual. It is a reflection and should be read for the pleasure ofthe questions it provokes, not for the utility of the pat answersit provides. It is written as a jazzlike play in a mode of cheerfulskepticism: skeptical about the already published obituaries fordemocracy, as well as the related enthusiasm for reviving democracyvia the irresistible power of the technological imagination. It isan improvisation on a theme of democracy and trust. Simply put: Candemocracy survive without trust?

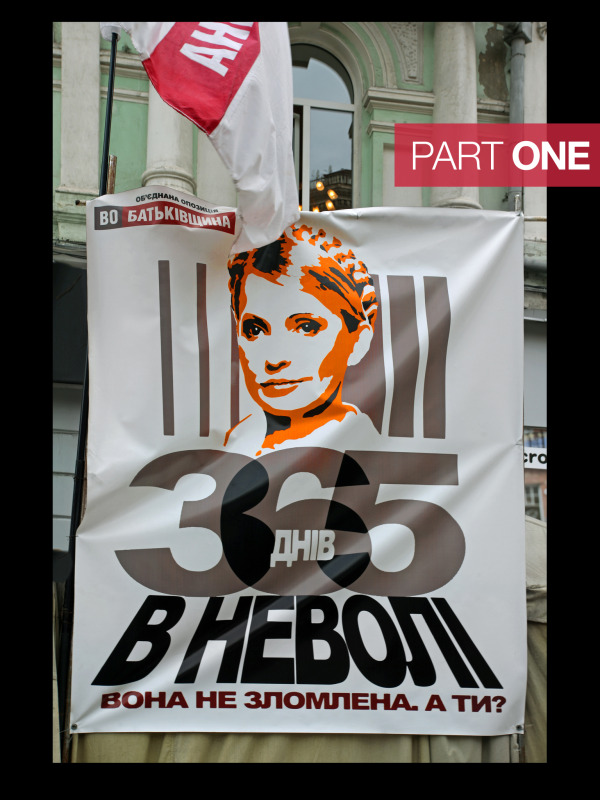

Opposition poster againstPresident Yanukovych, displayed during a protest in Kiev, Ukraine,in September 2012. Former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko wassentenced to seven years in jail for a gas deal with Russia. Image:SVLuma/Shutterstock

Voter mistrust

Elections dont change anything, readsgraffiti scrawled across a wall in the center of my hometownof Sofia, Bulgaria. If elections changed something, they would bebanned.

No one remembers when the graffiti first appeared or who wroteit probably some young anarchist or not-so-young street artist.No one knows why the well-to-do owners of the building neverremoved it (that the municipality did not clean it is no mystery,as it never has money for such things). But as time passed, thegraffiti began to serve as a motto for the journey of Bulgariansthrough the wilds of democracy. When asked, Bulgarians never missthe opportunity to inform pollsters, reporters, and friends thatelections wont change a darned thing. And it is not onlyBulgarians who speak and think this way.

Crowds assemble in Kiev on thefirst day of the Orange Revolution to protest Ukrainespresidential election.

Image: Serhiy/CreativeCommons

To underscore the publics cynicism about contemporary partypolitics, its worth retelling the story of Vladimir Boyko. A young Ukrainian, Boyko isambitious, pragmatic, and entrepreneurial. In 2004, he was one ofthousands of young people who spent their days and nights on Kievscentral square protesting the falsification of Ukrainespresidential elections. He and people like him were the symbol ofthe nations dream for genuine democracy, expecting it to bringthem prosperity, opportunity, and change. Alas, as we know, whatUkraine witnessed instead in its post-Orange revolutionary decadehas been the corruption, arrogance, and hubris of those in power.Ukrainian oligarchs have turned out to be the only truebeneficiaries of the change. Soon after the revolutionary days, theleaders of the movement went on the offensive, bitterly attackingnot corruption but one another. The economy was in free-fall. Therevolutions villains were thereafter reimagined as the saviors ofthe nation. As for Boyko, he ceased being interested in changingthe nation and focused instead on making money. He is now in thebusiness of crowd renting. His company, Easy Work, has assembleda database of several thousand students, pensioners, and unemployedpeople whom it can mobilize at a moments notice to turn up atpolitical party demonstrations anywhere in Kiev, stand for hours ata time, and cheer or jeer on cue. Ideology hardly matters to Boykoor his employees when they agree to play citizens in suchdemonstrations. What really matters is that the money usuallyfour dollars per hour is paid on time. What was civic activism inthe days of the Orange Revolution is mercenary activismnowadays. Democracy no longer stands for politics; it is a businessproposition.

Its reasonable to say that Bulgaria and Ukraine are extremeexamples of the disillusionment with democracy. But its also truethat the mood of Bulgarian and Ukrainian voters is representativeof a wider trend. In the last three decades, people throughout theworld are voting more than ever before, but in many Europeancountries the majority of people no longer feel that their votereally matters. There is a secular trend of decline of theelectoral turnout in most of the Western democracies, and thepeople least likely to vote are the poor, the unemployed, and theyoung in short, those who should be most interested in using thepolitical system to improve their lot. The dramatic decline oftrust since the 1970s is sharply illustrated by the fact thatanyone under the age of 40 in most Western societies has lived hisor her entire life in a country where the majority of citizens donot trust their national government.

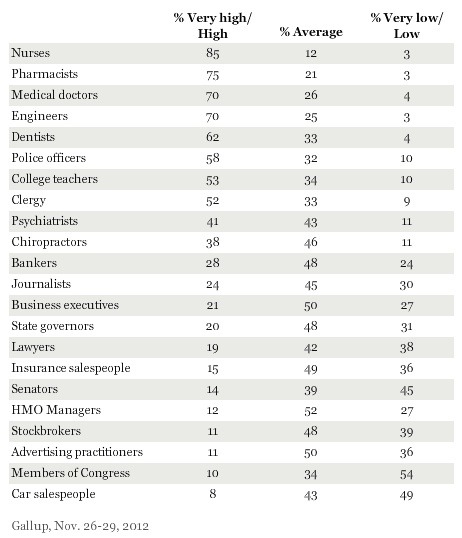

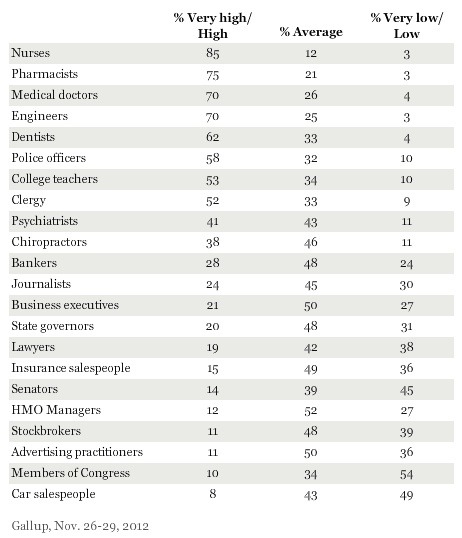

Gallup asked U.S. residents to ratethe honesty and ethical standards of people in certainprofessions as very high, high, average, low, or very low. Membersof Congress were regarded as shiftier than every profession exceptcar salesmen; Senators fared only slightly better.

So while there seems to be a more universal appeal of democraticprinciples, and while the number of democracies in the world grows(with Libya and Egypt being the latest arrivals), trust in thecomponents of a democracy parties, elections, parliaments,governments is in serious decline. Professor Mary Kaldor and herteam at the London School of Economics recently conducted a studyon the sources of the new protest movements in Europe. Resultsindicate that many of the participants arent protesting specificgovernmental policies so much as they are expressing a generalbelief that powerful interests have captured democraticinstitutions in many Western democracies and that citizens arepowerless to bring change. Not surprisingly, a growing number ofpeople tend to vote for protest or extreme parties. The newpopulism that is on the rise in Europe and the United States,however, does not represent the aspirations of the repressed but,rather, the frustration of the empowered. It is not a populism ofthe people enthralled with the romantic imagination ofnationalists, as was the case a century and more ago. It is apopulism of the pessimistic and threatened majority fearing thattheir demographic decline will also mean a loss of power. In thewords of American political theorist Mark Lilla, It gives voice tothose who feel they are being bullied, but this voice has only one,Garbo-like thing to say: I want to be left alone.