O ver five years of research and writing, I accumulated a long list of debts, most of which will never be properly repaid.

At the George C. Marshall Foundation, Im grateful to Paul Barron and Jeffrey Kozak for their advice and help in the archives, as well as to Brian Shaw and Rob Havers for their support. Mark Stoler of the University of Vermont and Barry Machado of Washington & Lee generously shared their wisdom and deep knowledge whenever I asked. A number of excellent researchersNikki Weiner, Terry Sun, Jacob Glenn, Yanping Liu, John Chen, Chen Gong, Josh Hochman, and Rhys Dubinprovided crucial help at various points along the way. Thomas Sung, Rebecca Soong, and John L. Soong Jr. vividly recounted their personal experiences.

In China, I relied on the help of some people I knew already and many more that I was meeting for the first time, all of them exceedingly generous. Peter Hessler, Jeff Wasserstrom, Emma Oxford, Maura Cunningham, Nicole Barnes, Charlie Edel, Ren Xiao Shan, and John Pomfret offered valuable contacts and advice. In Beijing, I had fascinating discussions with Niu Jun and Zhang Baijia, and benefited from the hospitality of Liu Gang. In Chongqing, Chen Guangmeng, Qian Feng, and Han Qing were immensely helpful, as were He Wen in Shaanxi and Xiong Hua Wu in Kuling. In Nanjing, Michael Zhang, Guo Biqiang, Xiao Zhencai, Dong Guoqiang, and Edmond Yang all gave lavishly of their time, knowledge, and enthusiasm. William Chan was a tremendous fellow traveler and intellectual partnerand deserves many additional thank-yous for his ongoing friendship and advocacy.

At New America, Im thankful to Steve Coll, Anne-Marie Slaughter, Andres Martinez, Peter Bergen, Becky Shafer, and Kirsten Berg for building an unparalleled infrastructure and fostering an unparalleled environment for writers trying to make progress on first books. At NYU, Mike Williams supported the final stages. Jose Fernandez and Andrea Gabor lent me a beautiful place to write.

A long list of friends, mentors, and colleagues talked through or read some or all of the manuscript (in a few cases more than once): Alan Schoenfeld, Patrick Radden Keefe, Mira Rapp-Hooper, Kurt Campbell, Harold Tanner, Gideon Rose, Jonathan Tepperman, Stuart Reid, Rebecca Lissner, Jacob Freedman, Jake Sullivan, John Gaddis, Mike Fuchs, Marc Dunkelman, Katharine Smyth, Dan Brook, Richard Feinberg, Tom Meaney, Dan Schwerin, Jim Kurtz-Phelan, Jared Leboff, Chris Heaney, Ryan Floyd, Liaquat Ahamed, Joshua Cooper Ramo, Arne Westad, Barry Machado, Mark Stoler, and Paul Barron.

My justly storied editor, Star Lawrence, got what I was trying to do from the beginning and patiently and expertly saw it through the end. Thanks also to Emma Hitchcock and Rachel Salzman at Norton. And the fantastic Tina Bennett not only relentlessly championed the book at every turn; she also seemed to always have a great idea or reassuring word at just the right moment.

My wonderful in-laws, Jessie and Jim, have been supportive and encouraging in countless ways, including by providing an idyllic Nova Scotia refuge for reading and writing. My sisters, Rachel and Abby, bolstered me when I needed bolstering. I owe my parents, Phyllis and Jim, more appreciation for more reasons than I can start to articulate (or even recognize)but anyway, as they know, ingratitude may be the truest testament to good parenting.

Finally, and most of all, thank you to Darin, who talked me through every travail, read every word twice, and gave me the fortitude to start in the first place.

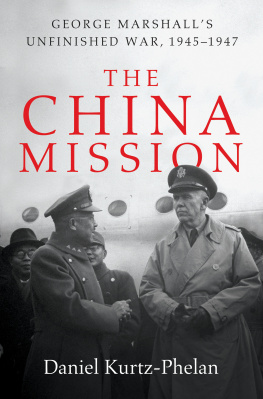

Copyright 2018 by Daniel Kurtz-Phelan

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Chris Welch

Production manager: Lauren Abbate

Jacket design by Charles Brock

Jacket photograph by George Lacks / The LIFE Picture Collection / Getty Images

ISBN: 978-0-393-24095-5

ISBN: 978-0-393-24308-6 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

To Darin

History will be kind to me for I intend to write it.

WINSTON CHURCHILL

So long as I do not give a damn about what they say in the future, I probably will be able to do a fair job at the present time.

GEORGE MARSHALL

O n June 5, 1947, five months after leaving Nanjing, Secretary of State Marshall traveled to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to receive a twice-postponed honorary degree from Harvard. Two years before, war had forced him to forgo it; one year before, the China mission had. Finally at Harvard, he took the opportunity to share a few words. They would become the most famous of his life.

In his matter-of-fact way, Marshall described Europes devastation and what it meant for America. He highlighted the menace of hunger, poverty, desperation, and chaos. He outlined the imperative of breaking the vicious circle and restoring the confidence of the European people. He called on his country to do whatever it is able to do to assist in the return of normal economic health in the world, without which there can be no political stability and no assured peace. Yet there was a catch: America could achieve little on its own. It should be willing to offer assistance on a previously unthinkable scale, but only if the recipients themselves took certain steps. The initiative, Marshall said, must come from Europe.

Truman decided to call the aid effort the Marshall Plan, since only naming it after Marshall gave it any hope of clearing Congress. It would be the largest foreign-assistance package in history, nearly $13 billion in total, a check on Soviet expansion, a shining example of American leadership. As in China, Marshall saw the dangers of chaos and desperation. As in China, he saw overcoming those dangers as the precondition to overcoming a Communist threat. Unlike in China, he saw partners willing to do what only they could to make assistance work.

Marshall had arrived back in Washington in January. Ahead of his return, the Senate had unanimously confirmed him as secretary of state, and messages of congratulations and offers of help had poured in (including from, of all people, Patrick Hurley). When he reached Washington, Katherine and Caughey along, Marshall took care of one persistent rumor before taking up his new task. He reiterated to reporters that he would not run for president in 1948, or ever. A tense, unsettled world gave him enough to catch up on without political distractions.

There were challenges everywhere, and for thirteen months Marshall had thought of little besides China. It did not take long for him to start repeating the warnings and exhortations of his final days as army chief of staff, now with new urgency and perspective. Peace has yet to be secured, he told students weeks into the job, and how this is accomplished will depend very much upon the American peoplea heavy responsibility, but shirked at great peril. We can act for our own good, he would declare, by acting for the worlds good.

When Marshall first went before Congress as secretary of state, however, his previous mission dominated discussion. Behind closed doors, he was as blunt as he had been with Chiang. He laid out the dilemmas and what it would take for American help to make a real difference in China. Certain things have to happen over there, he said. The great problem is how much deterioration sets in before those things do happen.

Next page