All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This is the first full biography of Chiang Kai-shek for almost three decades. It would not have been possible without drawing on extensive research into the period up to 1949 by scholars in mainland China and Taiwan, Hong Kong, the United States, Britain, Australia, France and elsewhere. I am grateful to all those whose work is referred to in the text or appears in the source notes. I also benefited from conversations with Lu Fan-Shang, Chen Yung-Fa and Yu Mii-ling of the Academia Sinica, Professor Jiang Yung-chiang, and officials at the Government Information Office and Kuomintang Party headquarters in Taipei where K. Y. Kuo was extremely helpful, both in arranging meetings and in providing his four-hour video recordings of the Young Marshal. Also in Taiwan, Jason Blatt gave ever-cheerful help; Windsor Chen indicated contacts; and Parris Chang spurred ideas on Chiangs last year on the mainland. I am indebted to the librarians at the Academia Sinica, Taipei Times and the China Post. Since this book may not be to the taste of some in Taiwan, I would like to stress that the responsibility for what I have written is mine alone. In Hong Kong and mainland China, I am particularly grateful to Willy Lo Lap-Lam, Mark ONeill, Jasper and Antoaneta Becker, John Gittings and Matthew Miller, to Michelle Wan in Shanghai, and for the assistance of guides on visits to key places in Chiangs life.

I owe a particular debt to two people who read the manuscript in its final stages; Keith Stevens has been a constant fund of useful suggestions and provided great linguistic help while Rana Mitter was a steady source of support and assistance, in particular in coming up with significant comments that improved the manuscript in its final stage. In Cambridge, Hans van de Ven was kind enough to let me see the manuscript of his book on the Chinese Army as well as advice on various points. Frederic Wakemans 2003 biography of the Nationalist police chief, Dai Li, provided insights into that powerful figure. In Oxford, I had illuminating conversations with Stephen Tsang at St Anthonys and with Graham Hutchings, who also provided the lead to photographs from the Nanking archive. I also benefited from the help of Frank Dikotter and Gary Tiedemann at the School of Oriental and African Studies, and of conversations with Shu Yun, Eddie U, Ann and Don Morrison, and Jean-Philippe Beja. The late Doon Campbell was good enough to provide papers from his time as Reuters correspondent in Chungking.

The library of the SOAS in London was an invaluable resource, and I would like to thank the staff for their help, in particular the Chinese librarian, Mrs Small. As well as academic works, SOAS proved to be a trove of books and diaries by contemporary visitors to China, many of which do not appear to have been used before, and for the files of the North China Herald which I read from 1911. I have also drawn on reporting by correspondents in China whose work has been little used by previous writers on the period. For their descriptive scope and detail, I am in debt to Hallett Abend, Jack Belden, James Bertram, W. H. Donald, Rhodes Farmer, Peter Fleming, Henry Misselwitz, Edgar Mowrer, Robert Payne, Arthur Ransome, Harold Timperley, Seymour Topping, Teddy White, and anonymous stringers for Reuters (plus Christopher Isherwoods wonderful account of his journey to war with W. H. Auden). In Paris, the staff of the Foreign Ministry Archives helped to identify documents from the French Concession in Shanghai. In Los Angeles, Kaustuv Basu and Stella Lopez at the Annenberg School of Communications tracked down and supplied Gardner Cowless privately printed memoir used in .

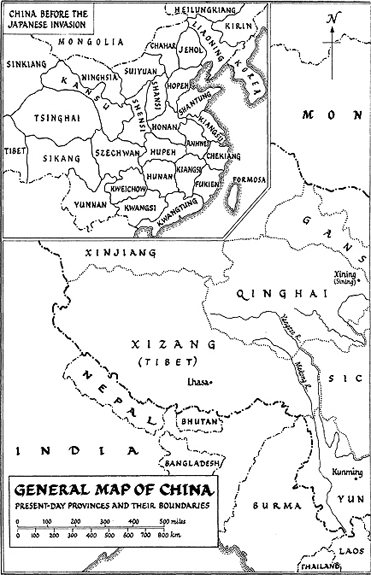

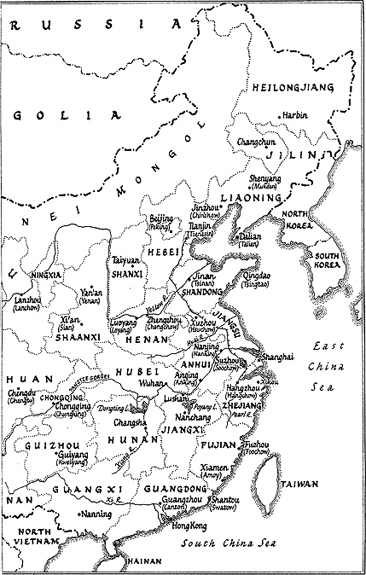

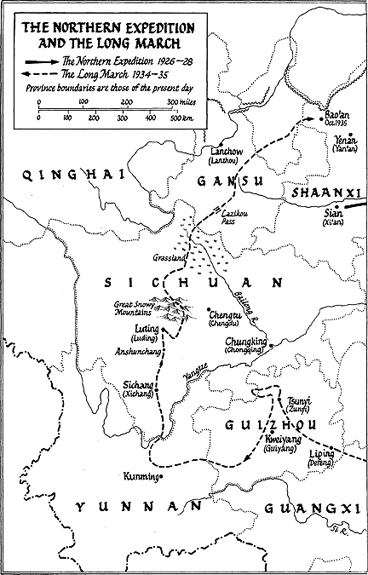

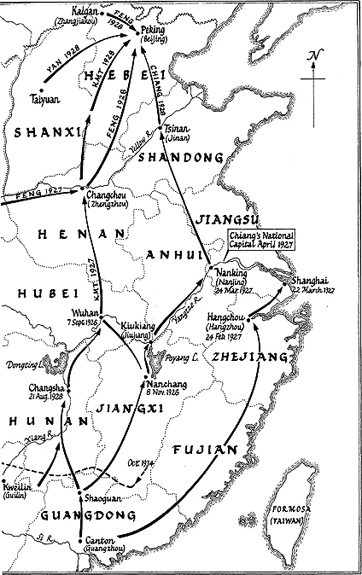

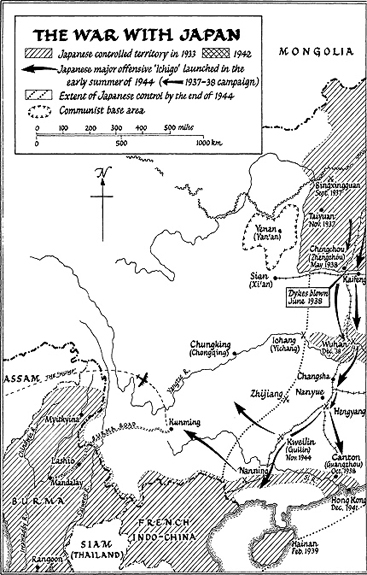

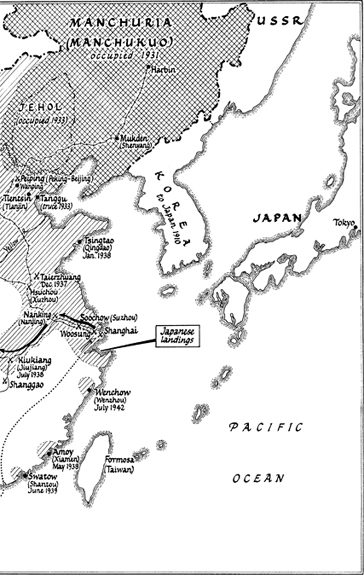

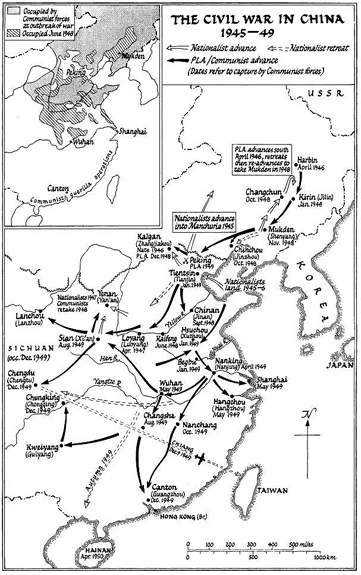

Andrew Gordon not only initially commissioned the book, but also understood that Chiangs story deserved to be treated in full. His editing suggestions moved the narrative through some roadblocks, and sharpened the final draft. I owe my usual debt to Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson both for his belief in a new biography of Chiang, and his encouragement along the way. Martin Bryant saw the book into production with efficiency and eminent good cheer. Gillian Kemp provided sharp-eyed copy-editing. Reg Piggott turned complex campaigns into clear map lines. Edwina Barstow produced an impressive array of photographs. Andrew Armitage provided the expertly constructed index while Caroline Ransford gave the book a final tooth-combing. Sara Fenby contributed invaluable technical assistance, and Alexander Fenby helped on various travels. Hamish McRae offered insight; Jack Altman provided illuminating leads on Japan; and David Tang was generous with the loan of volumes from the China Club in Hong Kong. For hospitality during the writing and for acting as sounding boards as I worked my way through the complexities of the Chiang saga, I am indebted to Peter Graham, Ginette Vincendeau and Simon Caulkin, Sally and John Tagholm, Lisa and Andr Villeneuve, Maa and Michael Unsworth, Ann and David Cripps, and Rosamund and Etienne Reuter.

My greatest debt, as always, is to my wife, Rene, both in the research, and with the innumerable improvements she brought as first and last reader. She also put up with my growing obsession with my subject, and the dislocations that a project like this inevitably involve in everyday life. Whatever this book is worth, it would have been much less without her.