Victorious in Defeat

Copyright 2023 by Alexander V. Pantsov.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Translated from Russian by Steven I. Levine.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Adobe Garamond type by IDS Infotech Ltd.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022934236

ISBN 978-0-300-26020-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my wife,

Ekaterina Borisovna Bogoslovskaia,

I dedicate this book with love

Contents

Spelling and Pronunciation of Chinese Words

The English spelling of Chinese words and names used in this book is based on the pinyin system of romanization (use of the Latin alphabet) to represent the pronunciation of Chinese characters. I follow the modified pinyin system used by the Library of Congress, which replaces an older system with which readers may be familiar. Thus, for example, I spell the name of Chiang Kai-sheks second wife as Song Meiling, not Soong May-ling. (Both romanizations yield the same pronunciation: Sung Meiling.) For the same reason I spell the name of Chinas capital as Beijing, not Peking. Following accepted practice, however, I use the traditional English spelling of the subject of this biography, Chiang Kai-shek, not Jiang Jieshi, as well as the names of his children, Chiang Ching-kuo, not Jiang Jingguo, Chiang Wei-kuo, not Jiang Weiguo, and Chiang Yao-kuang, not Jiang Yaoguang. I also use the traditional English spelling of the family name of his grandchildren and great-grandchildrenChiang, not Jiang, as well as the name Sun Yat-sen, not Sun Yixian, names of the cities Canton, not Guangzhou, and Taipei, not Taibei, the name of a famous Shanghai avenue, Nanking Road, not Nanjing Road, and the names of famous institutions such as Peking (not Beijing) University, Yenching (not Yanjing) University, and Tsinghua (not Qinghua) University.

The pronunciation of many pinyin letters is roughly similar to English pronunciation. However, some letters and combinations of letters need explanation:

Vowels:

A like a in father

AI like the word eye

AO like ow in cow

E like e in end

I like i in it

IA like ye in yes

O like o in order, except before the letters ng, when it is pronounced like the two os in moon

U like the second u in pursue when it follows the letters j, q, x, and y; otherwise, like the double o in moon, except in the vowel combination UO the u is silent

like the second u in pursue

YA like ya in yacht

YE like ye in yet

YI like ee in feet

When two separately pronounced vowels follow each other, an apostrophe is inserted to indicate the syllable break between them. Thus, Xian, for example, is two syllables whereas xian is just one.

Consonants:

C like the letters ts in tsar

G like the hard g in get

J like j in jig

Q like the letters ch in cheese

R in initial position, like the s in vision; at the end of a word, like the double r in warrior

X like the s in soon

XI like the shee in sheet

Z like the letters dz in adze

ZH like the j in jockey

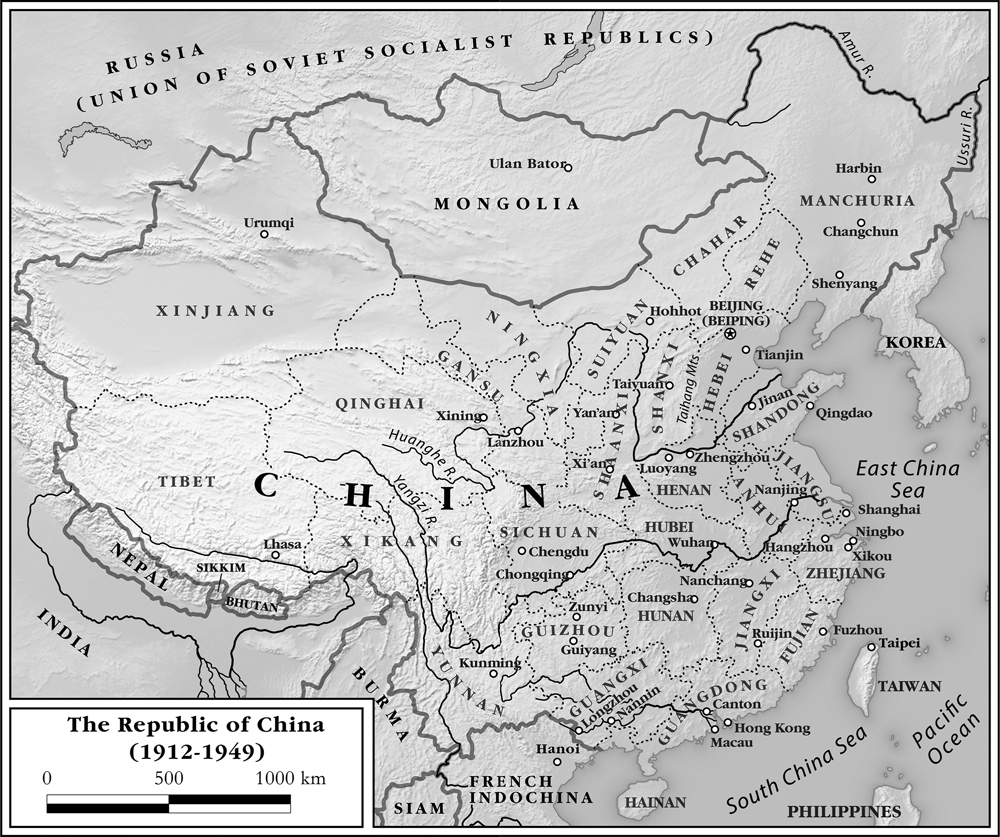

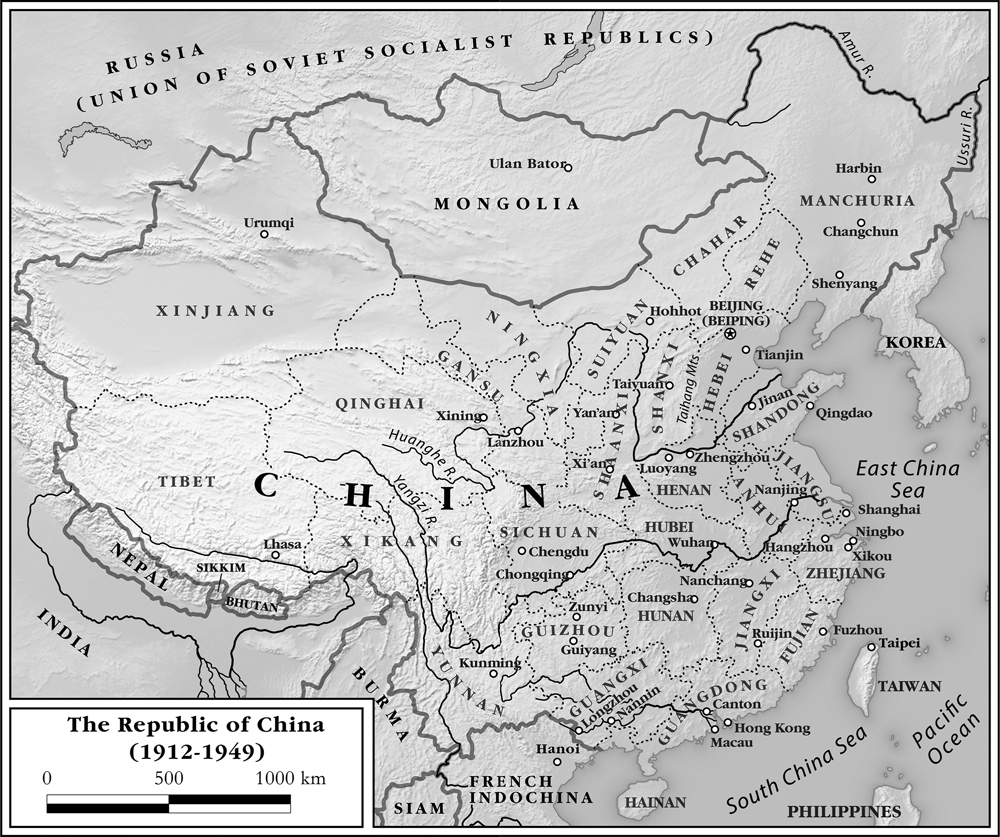

Victorious in Defeat

(Map by Erin Greb)

Introduction

In May 1949 the North China city of Qingdao, located on the shore of the Shandong peninsula, was gripped by panic. Everyone was anticipating the day when the American warships, stationed in adjacent Jiaozhou Bay, would depart, after which the city would inevitably be seized by communist forces. A civil war was raging in China, and during the past two years the insurgent Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) of the communist leader Mao Zedong had repeatedly inflicted defeats on the government forces of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Everyone was afraid that the communists would carry out a slaughter even bloodier than the one that, according to rumors, had taken place in a number of Shandong cities in November 1947; in Weihaiwei alone at that time the communists had massacred several thousand peaceful inhabitants. The inhabitants were leaving the city in droves; excited crowds were besieging passenger ships.

However, the rumors about Chiang Kai-sheks arrival and the departure of US ships in five days were false. The Generalissimo had not flown to Qingdao in early May to hold negotiations with the commander of the American fleet.

Chiang had long realized that he could not count on American military support, so in early 1949 he had begun preparations to redeploy his forces from Qingdao to the area of Nanjing and Shanghai. As for the Americans, he had decided to inform them of his departure no earlier than three days prior to the completion of the Guomindang army evacuation.

On May 4 Chiang discussed the situation with the commander of the Twenty-first Army Corps defending Qingdao, General Liu Anqi, insisting that the troops be withdrawn as soon as possible. We dont need to guard the gates any longer to provide for the evacuation of the Americans, he said irritably. Qingdao fell that same day.

A week earlier the communists had seized Shanghai, the largest Chinese metropolis. Nanjing, the capital of China, had already been in their hands for a month. The troops of the PLA flowed south in a mighty stream, and the civil war was inexorably drawing to a close. Chiang Kai-sheks army was falling apart, and many of the closest associates of the Generalissimo, including several members of his family, fled the country. His main ally, the United States of America, which had spent hundreds of millions of dollars in military and financial aid to Chiang before and during the final civil war in China, ultimately also had to throw him to the mercy of fate.

Needless to say, it was Chiang Kai-shek, his government, and his generals who were most responsible for the defeat. However, his debacle also marked a defeat of the American policy in China that had been extremely contradictory. On the one hand, the Americans had rendered massive financial and military help to Chiangs regime, but on the other they had made serious mistakes that made the situation worse.

The loss of China was to some extent preconditioned by President Franklin D. Roosevelts behavior during the Yalta Conference with Josef Stalin in February 1945, when, in effect, he sold Chinas Manchuria to Russia in exchange for Russian entry into the Japanese war. Moreover, he did it behind Chiang Kai-sheks back. Would the Chinese Communists have defeated Chiang Kai-shek had the Russians not occupied Manchuria and provided critical assistance to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) at a decisive moment? We cannot know the answer for sure, but we do know that this region played an enormous role in the Communist takeover of China. It was indeed an anvil of Communist victory.

Next page