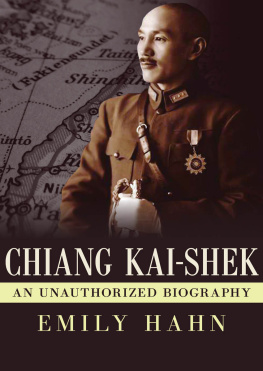

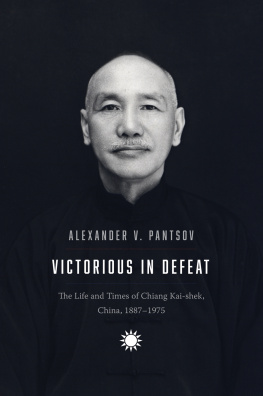

Chiang Kai-Shek

An Unauthorized Biography

Emily Hahn

EMILY HAHN

FROM OPEN ROAD MEDIA

Find a full list of our authors and

titles at www.openroadmedia.com

FOLLOW US

@OpenRoadMedia

1 FLASHBACK 188794

That night in Takata, near the northwest coast of Japan, there was a dinner party in a restaurant. Uniformed men with shaved heads and stockinged feet sat cross-legged on the matting floor and toasted each other, and laughed a good deal and sang marching songs. They were young and cheerful. It wasnt an elaborate or expensive party; just a routine dinner, a farewell gesture from the Japanese officers of the town garrison for three Chinese brothers in arms. These Chinese had been with them for several years, training in the Imperial Army by special arrangement with the War Office in Peking. Now they were going home. Their plans, like many other Chinese plans, had suddenly been changed by an accident, due to some clumsy unknown, miles away in Hankow. There, a bomb had gone off in a cellar and blown the lid off the latest revolution against the Ching Dynasty. It was October 1911.

Somebody filled one of the tiny cups with water instead of rice wine, and with a sweeping gesture handed it to his neighbor, a Chinese. Military people dont drink sake, he said. Please drink water instead. According to the bushido spirit of Japan, drinking water means that the soldier wont return alive.

All the Japanese nodded approvingly and in silence watched the little ceremony that followed. Two of the guests took a sip, but the last one to hold the cup, a solemn young man named Chiang Kai-shek, swallowed all the water that was left.

Gentlemen, thank you for the honor you have done me, he said.

And as he drank his face was red with emotion, said General Nakaoka, trying valiantly in 1928 to recall whatever he could of the long-forgotten incident. Whoever dreamed that the student of those days would ever be chairman of the Chinese Government? None of us thought that Mr. Chiang was going to be a historic personality.

Still less, he might have said, did anybody in the regiment think that some day the Japanese, above all people, would have violent reactions to Chiangs name. In 1911 he was one of the most obscure Chinese students that had ever been sent over to finish his military training in Asias up-to-date army. Most youths in his category were related to the noble families of China and had got their places through political pull, but Chiang Kai-shek was a nobody.

The officers were sorry later on that they had neglected to notice him. By the time Nakaoka gave his newspaper interview the Japanese had developed a keen interest in that all but forgotten young man, and were even proud of him. In 1928 he was famous as the Chinese leader who had suddenly broken with Russia and taken the new Republic out of Communist clutches. Still, there it was; nobody among the Japanese in his old regiment remembered him except in a vague way, in that scrap of the generals reminiscence. Only a sergeant, a man named Shimoda, could add more to the picture.

The only thing remarkable in him, said Shimoda, was the impressive and forbidding expression which would instantly come upon his face when he was ordered to clean the stables.

The twenty-four-year-old Chiang sailed to Shanghai in a state of elation that his code of manners made it necessary to conceal. It was against his philosophy of self-control to exhibit emotion, but he had waited a long time for this moment. This, he felt, was it at last; this time the revolution would succeed. He liked the Japanese well enough after all these years of arduous training; he admired their endurance, and he had long since got used to their scanty diet of cold rice garnished with a little fish and pickle. He knew he had been lucky to get the chance of training with the only modern army in the Far East. Most of the boys sent over from home on the government training scheme were naturally pro-Manchu. But Chiang was different. Already, in spirit, he was a seasoned revolutionary. Nor was it only in spirit that he knew his way around that dimly lit world of the fugitive in which his revered leader, Sun Yat-sen, had lived his adventurous life. Already he felt like a veteran. He didnt look like onehe looked like a boy of sixteenbut it is the feeling that counts.

Chiang knew Shanghai well; the foreign settlements, the great walled estates, the hotels, and the drab Chinese city full of pig-tailed workers. It looked normal when he landed, but something was going on behind the humdrum faade of streets and people. Not only China had been rocked by that amateurish little bomb. The world was following developments.

The French Concession and the International Settlement offered the conspirators who were Chiangs friends their only safety in all the country. Protected by the flags of Europe, Sun Yat-sens followers had for years been holding their meetings and taking up collections for armaments.

As soon as his ship had docked, the young soldier hurried to the house of his good friend Chen Chi-mei. Whatever was happening, Chen would know the true story. There had been other alarms and they had always turned out to be false or abortive, but this time, Chiang knew, things were better prepared than they had ever been before. There would be popular support in widespread districts. This time, revolution against the Manchus couldnt be quelled. That was why he had insisted upon coming back to his country instead of staying on in the hope of more training. One couldnt go on forever just preparing. A keen young soldier must find his place in the sun; he need not forever accept a role in the background, giving way to spoiled scions from the higher social circles of Peking. There had been a lot of that alreadytoo much. Chiang had suffered a long, long time from resentment and a feeling of neglect. He had a passionate and jealous nature.

Next page