Contents

Introduction

I T IS a commonplace irony that The Princethe classic handbook on power politicsshould have owed its birth to the collapse of its author's own political career and to the practical failure of his most cherished military innovation.

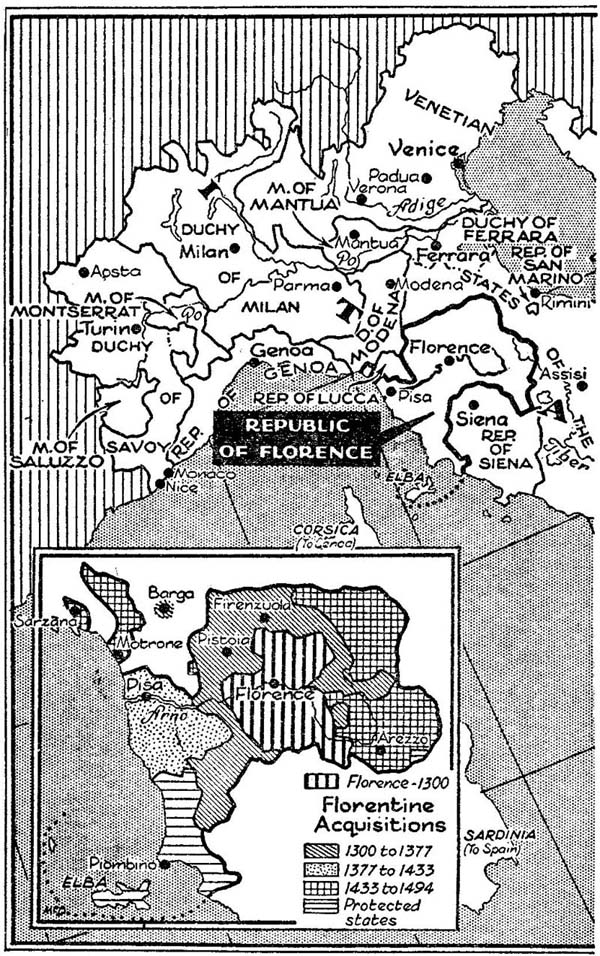

Machiavelli's official entry into politics occurred in 1498 with his appointment as Secretary to the Second Chancery of the Signoria, a position rather loosely defined, involving him in military matters as well as domestic and foreign affairs. In this post he remained until the fall of the Florentine Republic in 1512. Through all his years in office, despite pronounced reservations about the generally conciliatory policies of his government, he remained loyal to it and served his superiors with tireless energy. When Pier Soderini was elected Gonfalonier, or chief magistrate, of the Republic in 1502, Machiavelli became one of his most trusted assistants. He was assigned to important missions both in Italy and abroad. The lengthy reports he submitted in the performance of these duties bear evidence of his sagacity as an observer, quick and sure in locating the center of power in any political situation and accurate in assessing its strength, but somewhat unskilled in the game of man-to-man diplomacy. They also attest to his passionate concern for the security of his homeland and his readiness to seek solutions that lay beyond the strict limits of his professional competence and authority. He was also ordered to draw up proposals on some of the vexing issues facing the Republic. These reveal in capsule form some of the important ideas we find in his later political writings.

Perhaps his finest hour came in 1509 when, after a fifteen-year struggle, the Florentines finally reduced Pisa into submission. Much of the credit for this feat belongs to Machiavelli. Though by no means a military man, he actually directed the land and sea blockade that brought about Pisa's capitulation. Moreover, the civilian troops who had manned the operation had come into being at his insistence and had been trained under his supervision. On this occasion his conviction, one which runs like a refrain through nearly all of his political writingsthat a healthy state must rely solely upon its own citizen forces in warbore fruit. It was to do otherwise three years later at Prato, when Machiavelli's career and the Republic foundered together.

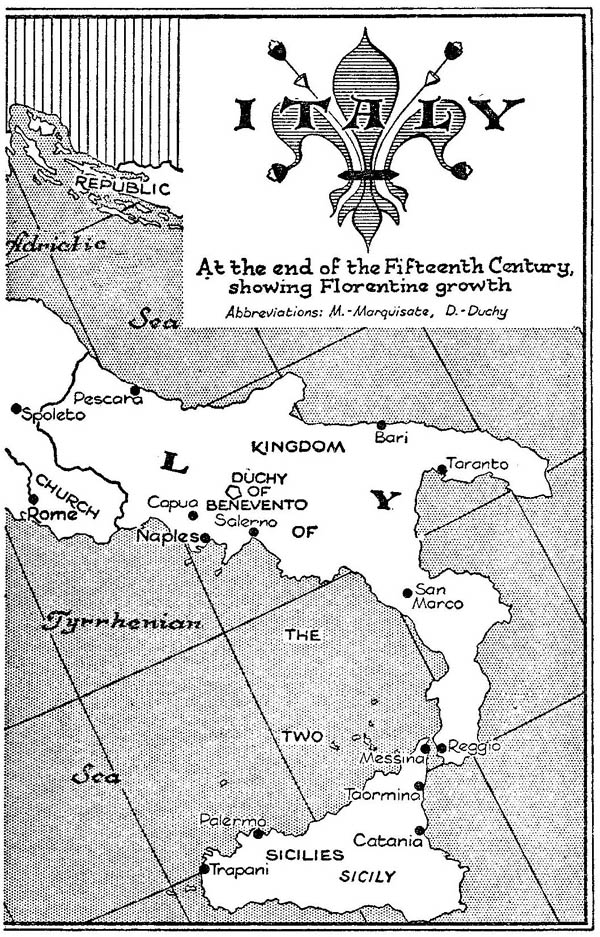

Perhaps the real cause of this calamitous event goes back to Soderini's insistence upon friendship with France as a cardinal rule of his foreign policy. Costly and difficult as it often proved, this policy nevertheless served to protect Florence from the threats of her powerful neighbors so long as France continued to count in the affairs of the peninsula. In 1511, however, Pope Julius II (together with Venice, Spain, and England) organized the Holy League and launched a campaign to drive the French out of Italy. During the war that ensued both the Holy League and the French sought assistance from Florence, but Soderini, having sent a token force to the French, tried to avoid serious entanglement. The result was that Florence incurred the enmity of both parties and (as Machiavelli could have predicted) faced the likelihood of being pounced upon by whichever side emerged the winner. To avoid this danger, Soderini then labored to arm the Republic, relying not upon mercenaries, as had so often been done before, but upon a citizen militia of the sort that had proved its meritso it seemedin the struggle with Pisa. Machiavelli, the prime mover of this innovation, had doubtless inspired Soderini with some of his own confidence in it. Thus when the Holy Leaguethanks to the last-minute intervention of the Swisstriumphed over the French, the scene of action shifted quickly to the frontiers of the Republic. Spanish troops, accompanied by Cardinal de' Medici, soon appeared and demanded the overthrow of the government. Assured that the unfledged forces Machiavelli had recruited could withstand the invader, Soderini refused to give way. The Spaniards then attacked, choosing Pratoheavily garrisoned with green recruitsas their target. After only a short struggle the enemy effected a breach in the city wall, poured through, overwhelmed the fleeing defenders, and sacked the town completely.

This was on August 29, 1512. Two days later Soderini resigned and went into exile. The Medici, after an absence of eighteen years, reassumed control of Florence. Six weeks after Prato, Machiavelli was dismissed from office and banished from the city for the term of one year. Thus the scene was set for The Prince and The Discourses.

But not quite. Early in 1513 Machiavelli was suspected of complicity in a plot to overthrow the Medici government. He was arrested, tortured, and soon after released, his innocence having been satisfactorily established. The incident should have destroyed any lingering hope of a rapid reentry into politics under the new rulers, but The Prince itself is ample evidence that it had no such effect.

Machiavelli withdrew to the meager farm near San Casciano which his father had left him. There impending poverty troubled him, though he had been short of funds before. But enforced idleness in rustic surroundings for this restless man of forty-three was an entirely new burden. Throughout his fourteen years of service he had been a high-level functionary. He had visited some of the key trouble spots of his day and had represented the Republic on difficult missions in France, in Germany, in Rome, and in the petty courts of Italian princelings. He had dealt with some of the leading figures of his age, the movers and shakers of his world. Now, in Polonius' words, he was reduced to

be no assistant for a state. But keep a farm and carters.

How he reacted to this suddenly slackened tempo and reduced circumstances we know from a letter he wrote to his friend Francesco Vettori less than a year later. The mingling of trifling details with serious matters, the shifting of tone, alternating between genial humor and hints of despair, are typical of Machiavelli's familiar letters in which the salient features of his mind and character stand out strikingly:

... What my life is, I will tell you. I get up at sunrise and go to a grove of mine which I am having chopped down. I spend a couple of hours there, checking up on the work of the previous day and passing the time with the woodcutters, who are never without some trouble or other, either among themselves or with the neighbors. On the subject of this grove, I could tell you a host of interesting things that have happened involving Frosino da Panzano and others who wanted some of the wood. Frosino in particular sent for a few cords of it without telling me, and when it came to paying he wanted to hold back ten lire because he claimed I owed him that much as winnings from a game of cricca we played four years ago at the home of Antonio Guicciardini. I began to raise the devil. I wanted to accuse the carter who had come for it of theft. But Giovanni Machiavelli came between us and made us settle. Battista Guicciardini, Filippo Ginori, Tommaso del Bene, and certain other citizens each ordered a cord when that ill wind was blowing.

Next page

![Machiavelli - The Prince [2011 Intro, Forward]](/uploads/posts/book/253164/thumbs/machiavelli-the-prince-2011-intro-forward.jpg)