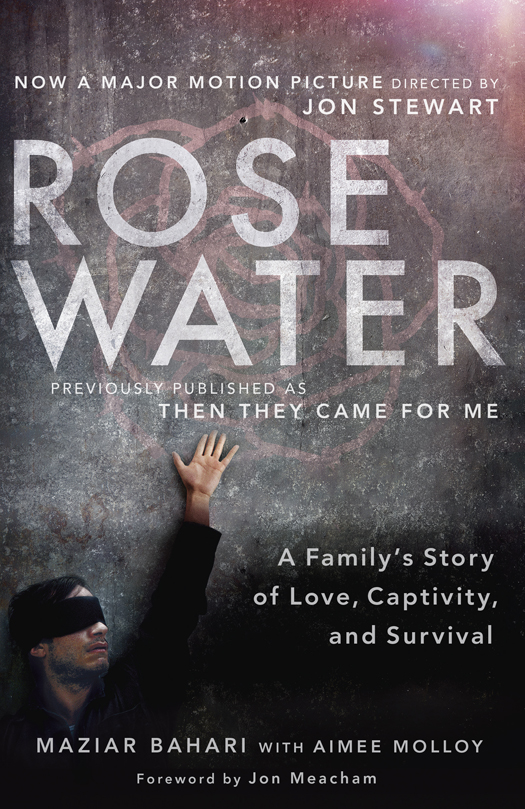

Copyright 2011 by Maziar Bahari

Foreword copyright 2014 by Jon Meacham

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Originally published in hardcover and in slightly different form in the United States as Then They Came for Me by Random House, an imprint and division of Random House LLC, in 2011.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

Arcade Publishing, an imprint of Skyhourse Publishing, Inc.: Seven lines from In This Blind Alley by Ahmad Shamlu, translated by Ahmad Karimi Hakkak, from Strange Times, My Dear. Reprinted by permission of Arcade Publishing, an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

Maryam Dilmighani: Translation of The Wind Will Carry Us by Forough Farrokhzad.

Reprinted by permission of Maryam Dilmaghani.

Sony/ATV Music Publishing: Excerpt from Sisters of Mercy by Leonard Cohen, copyright 1967 by Sony/ATV Songs, LLC. All rights administered by Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC, 8 Music Square West, Nashville, TN 37203. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Wixen Music Publishing, Inc.: Excerpt from Everybody Knows by Leonard Cohen, copyright 1988 by Sharon Robinson Songs (ASCAP), administered by Wixen Music Publishing, Inc. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bahari, Maziar.

Rosewater : a familys story of love, captivity, and survival / Maziar Bahari with Aimee Molloy.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-679-60419-8

Hardcover ISBN: 978-1-4000-6946-0

Trade paperback ISBN: 978-0-8129-8180-3

1. Bahari, Maziar. 2. Bahari, MaziarImprisonment. 3. Bahari, MaziarFamily. 4. IranHistory1997 Biography. 5. IranPolitics and government1997 6. Political prisonersIranBiography. 7. JournalistsIranBiography. 8. JournalistsCanadaBiography. 9. Motion picture producers and directorsCanadaBiography. I. Molloy, Aimee. II. Title.

DS318.9.B35 2010

365.45092dc22

[B]

2010053882

www.atrandom.com

Jacket design: Misa Erder

Jacket photograph: Shutterstock

v3.1_r3

To Moloojoon, Baba Akbar, Maryam,

Paola, and Marianna

They smell your breath

lest you have said: I love you,

They smell your heart:

These are strange times, my dear.

They chop smiles off lips,

and songs off the mouth.

These are strange times, my dear.

A HMAD S HAMLOU , 1979

Foreword

Jon Meacham

Documentarian and journalist Maziar Bahari has long been committed to telling the stories of others. In these pages he has his own tale to sharea compelling, unsettling account of how a regime, fearful for its power, decided to imprison a man whose only crime had been to report what was actually happening on the ground in Iran in a period of potential revolution. It is a particular story of global significance, for in it we see universal archetypes that recur again and again: a jealous, nervous state; a truth teller buffeted by forces beyond his control; a family in crisis.

Bahari was a correspondent for Newsweek magazine, covering protests that sprang up in the wake of the June 2009 elections in Iran, whenin the words of the titlethey came for him. And we soon learn that he was only the latest of his family to be persecuted by whichever regime had gained power over Iran. The Baharis offer us a unique window into the tumultuous history of Iran, a history still unfolding.

I was serving as the editor of Newsweek in those days, and Nisid Hajari, then the international editor of the magazine, and Christopher Dickey, our Paris bureau chief and Middle East editor, did brilliant, selfless work in attempting to secure Baharis release. Part of that campaign involved publishing op-eds calling on the regime in Tehran to do the right thing. In one such piece, for The Washington Post, I wrote: Some in the government of Iran would like to portray Bahari as a kind of subversive or even as a spy. He is neither. He is a journalist; a man who was doing his job, and doing it fairly and judiciously, when he was arrested. Maziar Bahari is an agent only of the truth as best he can see it, and his body of work proves him to be a fair-minded observer who eschews ideological cant in favor of conveying the depth and complexity of Iranian life and culture to the wider world. Few have argued more extensively and persuasively, for instance, that Irans nuclear program is an issue of national pride, not just the leaderships obsession.

When he was arrested, Bahari was at work under trying circumstances, which he describes early on. Having grown up under the despotic regime of the Islamic Republica regime under which information was controlled and severely limitedI understood that a lack of information and communication among a populace leads only to bigotry, violence, and bloodshed, Bahari writes. Conspiracy theories about unknown othersthe West, multinational companies, and secret organizationsbeing in charge of Irans destiny had stunted my nations sense of self-determination and, as a result, its will, leaving generations of Iranians feeling hopeless and helpless. I felt it was my job to provide accurate, well-reported information and, in doing so, help the world to have a better understanding of Iran and in my own way build a gradual path toward a more democratic future. I felt it was my job: We are better off because he believed that was his mission.

Journalists who put themselves in harms way are special people; theirs is an uncommon courage. Like many readers, many editors in the comfort of New York or of Washington can have only the slightest sense of the dangers faced by correspondents covering shooting wars or repressive regimes. Reading Baharis account of his arrest and imprisonment, I am filled anew with admiration and respect for those who do what I have never done, which is to confront the realities of war and of revolution eye to eye. I suspect you will be, too.

Contents

PART ONE

The Tunnel at the End of the Light

PART TWO

Neither Departed Nor Gone

PART THREE

Survival

Prologue

I could smell him before I saw him. His scent was a mixture of sweat and rosewater, and it reminded me of my youth.

When I was six years old, I would often accompany my aunts to a shrine in the holy city of Qom. It was customary to remove your shoes before entering the shrine, and the caretakers of the shrine would sprinkle rosewater everywhere, to mask the odor of perspiration and leather.

That morning in June 2009, when they came for me, I was in the delicate space between sleep and wakefulness, taking in his scent. I didnt realize that I was a man of forty-two in my bedroom in Tehran; I thought, instead, that I was six years old again, and back in that shrine with my aunts.

Mazi jaan, wake up, my mother said. There are four gentlemen here. They say they are from the prosecutors office. They want to take you away. I opened my eyes. It was a few minutes before eight, and my mother was standing beside my bedher small eighty-three-year-old frame protecting me from the four men behind her. I sleep without clothes, and in my half-awake state, my first thought wasnt that I was in danger, but that I was naked in a shrine. I felt ashamed and reached down to make sure the sheets were covering my body.