STRUGGLE OR STARVE

STRUGGLE OR STARVE

Working-Class Unity in Belfasts 1932 Outdoor Relief Riots

by Sen Mitchell

Foreword by Brian Kelly

2017 Sen Mitchell

Published in 2017 by

Haymarket Books

P.O. Box 180165

Chicago, IL 60618

773-583-7884

www.haymarketbooks.org

ISBN: 978-1-60846-892-8

Trade distribution:

In the US, Consortium Book Sales and Distribution, www.cbsd.com

In Canada, Publishers Group Canada, www.pgcbooks.ca

In the UK, Turnaround Publisher Services, www.turnaround-uk.com

All other countries, Ingram Publisher Services International,

This book was published with the generous support of Lannan Foundation and Wallace Action Fund.

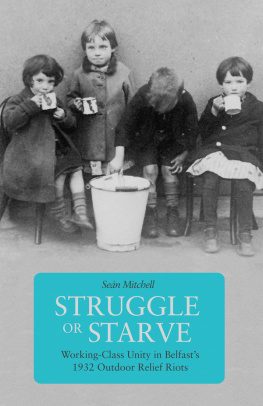

Cover design by Rachel Cohen. Cover image: Belfast Central Mission in 1932 organized to feed the children of the unemployed. Courtesy of Belfast Central Mission Archive. Special thanks to Wesley Weir

Printed in Canada by union labor.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To the memories of Bobby McCartan and Joe Johnny Rua. I ndil cuimhne.

GLOSSARY OF ORGANIZATIONS

Belfast Trades Council: Also known as the Belfast & District Trades Union Council. The council brings together representatives from trade unions from across Belfast.

Board of Guardians: An organization set up in the 1840s to oversee the Irish Poor Laws. The Guardians were elected by ratepayers and were tasked with the administration of the workhouses and the allocation of indoor and outdoor relief.

B-Specials: The Ulster Special Constabulary, composed of the A-Specials and the B-Specials, was Northern Irelands quasi-paramilitary reserve police force, set up in October 1920, shortly before the partition of Ireland. Overwhelmingly Protestant in membership, the A-Specials were abolished in 1920. Disbandment of the B-Specials was one of the central demands of the modern civil rights movement. They were abolished in May 1970.

Irish Republican Army (IRA): An armed republican organization, dedicated to the ending of partition and the creation of an Irish Republic.

Nationalist Party: A mainly Catholic political party, formed by members of the Irish Parliamentary Party who were based in Northern Ireland. It had a number of members elected to the Northern Ireland Parliament and was led by Joe Devlin until 1934, when he was replaced by Thomas Joseph Campbell.

Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP): A political party set up in 1924, linked to the trade unions. Prominent NILP figures in the 1930s included Jack Beattie and Harry Midgley.

Outdoor Relief Workers Committee (ODRWC): A committee set up on July 25, 1932, by Communists to organize those workers on Outdoor Relief schemes.

Republican Congress: An Irish republican and socialist political organization founded in 1934, including left-wing elements who had split from the IRA and the Communist Party of Ireland. Key figures in the group were Peadar ODonnell, Frank Ryan, and George Gilmore. The Congress dissolved in 1936.

Revolutionary Workers Groups (RWGs): A small Irish Communist grouping, formed in 1930 with the backing of the Soviet Union and its international network, the Comintern. It produced a paper, Irish Workers Voice (later Workers Voice), and was led by Sen Murray. Key RWG figures in Belfast included Tommy Geehan and Betty Sinclair. The group was renamed the Communist Party of Ireland in 1933.

Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC): The largely Protestant police force in Northern Ireland, founded on June 1, 1922, out of the Royal Irish Constabulary.

Ulster Protestant League (UPL): A loyalist organization set up in 1931 to safeguard the employment of Protestants. The UPL opposed any unity between Catholics and Protestants and in 1931 attacked an unemployment march organized by the RWGs. It produced a newspaper, Ulster Protestant, which carried the slogan Vote Protestant, Buy Protestant, Sell Protestant, Be Protestant.

Ulster Unionist Party: The largest political party in Northern Ireland in 1932. Its origins can be traced back to the Ulster Unionist Council, formed in 1905. The party was led by James Craig during the 1930s, who was also the prime minister of Northern Ireland.

FOREWORD

by Brian Kelly

Although the bare essentials of the extraordinary upheaval at the core of this study are familiar to trade union and working-class activists in Belfast and throughout Ireland, it is a revealing fact that until now the 1932 Outdoor Relief (ODR) Strike has never been the subject of serious, extended treatment. This is especially remarkable when we consider the vast literature that has grown up around the armed conflict that dominated life here in the closing decades of the last century, known euphemistically as the Troubles. Journalists from across the globe have dissected the causes and effects of this violence, with rare exception settling upon the banal tautology that Northern Irelands warring religious tribes could not help themselves from being drawn into an extended bout of reciprocal slaughter. University-based sociologists, political scientists, and historians have offered up only a slightly more sophisticated rendering, straining to absolve imperial rulers and regional elites from culpability in setting the context for sectarian antagonism, insisting that the most recent chapter in Belfasts long tragedy was driven by ethno-religious or ethno-national divisions that are essentially timeless and immutable, almost compulsive.

The conspicuous omission of the ODR strike from the narrative of Belfasts twentieth-century history demands an explanation, and although a detailed critique of the relevant historiography is not feasible here, it is possible to identify some of its main problems and in the process highlight the scale of what Sen Mitchell has managed to achieve in this important study. The absence of a serious Although the citys modern evolution is intricately bound up with the linen mills and shipyards, the docks, ropeworks, tobacco factories, and large engineering enterprises that formed the basis of its economy, we have almost no mature historical literature on the working class whose labor made Belfastfor a timean industrial powerhouse in the global economy.

The development of religious sectarianism as an enduring feature of life in the city is incomprehensible without some grasp of the relationship between the decline of rural northeastern Ulster, the pull of wage labor in industrializing Belfast, and the desperate competition generated by rapid, large-scale migration into a city in which Protestant men exercised an early monopoly over better-paid skilled labor, but no major study offers a broad, holistic analysis of this dynamic.

The turn in recent years to celebrating Belfasts industrial heritage as part of a rebranding project aimed at attracting tourism and multinational investment has not improved this dire situation. Driven forward by neoliberal advocates of privatization and free market ideology, the Titanic museum (the post-conflict citys signature development project) and the wider attempt to market a re-imaged Belfast purged of the traces of recent conflict has been framed as a celebration of the captains of industry and a paean to the citys entrepreneurial traditions. The new development has allowed some room for the sights and sounds of the shipyards but no real sense of the explosive class conflict or deep social inequalities that marked industrial Belfast.

Next page