To E.C.M.

Foreword

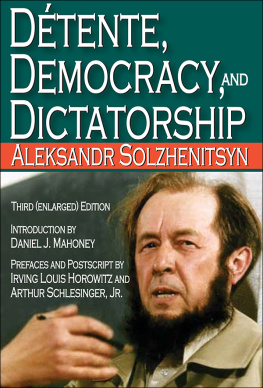

F OR US, TWO STUDENTS of the politics of peasantry who began teaching together in 1967 about revolution, the pleasure evoked by the publication in 1966 of Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World was akin to how members of a small cargo cult might have felt when they finally saw ships on the horizon. Moores was a work of enormous breadth and deep reflection that asked large moral questions about the creation of the modern world, including its inhumanities. Whats more, it did so with a clarity of purpose, a certain intellectual modesty of execution, and a painstaking attention to the best historical evidence available, all woven into a lucid argument. The book raised compelling questions: Was violence necessary for freedom? Could one calculate and judge the human costs of diverse paths to modernity so that rational evaluation was possible?

With the entire country focused on Americas military response to the armed struggle in Vietnam, senior scholars responded in scores of academic and popular journals to Moores findings on third world peasant revolutions. While their diverse answers are mostly forgotten, Moores questions remain ethical and historical challenges. Reading and rereading his extraordinary work continues to bear fruit.

Probing matters to their moral center, the book has outlasted the staying power of any one of its particular answers, theses, or explanations of how democratic and dictatorial states developed historically, More than a quarter century after its publication, when the works of his contemporaries who wrote on revolution as a romantic enterprise are long forgotten, Moores work, with its pessimistic finding that progress comes only at an awful cost, remains a fundamental source for anyone who hopes to understand the historical origins and potential for good and evil of modern states.

Moore begins with a question of obvious importance: Can we explain, comparatively, the historical development of three alternative paths to the modernliberal democracy, fascism, and communism? A remarkable feature of Moores analysis is the degree to which he takes the reader into his confidence as he mulls over the evidence. He does not provide theoretical linearity and closure, or imply that the evidence fits seamlessly together. All the jagged edges, gaps, and leaps in his argument are made manifest to the reader. Moore invites the reader to share the quest, to enjoy a dialogue with a learned, open, and generous teacher who, nevertheless, has not figured everything out. He raises many unanswered questions that require further investigation.

Moores discussion of exploitation is an example of this dialogic tone. He knows that most contemporary social scientists treat exploitation as a purely subjective concept. Moore, however, finds the subjectivist argument preposterous: How can nine-tenths of the peasants crop be no more and no less arbitrary an exaction than a third? (p. 471). An objective notion of exploitation makes better (if not perfect) sense and at least provides the possibility of an explanation (p. 471). Moores peasant is capable of both economic and moral judgments. Moore suggests that the contributions of those who fight, rule, and pray must be obvious to the peasant, and the peasants return payments must not be grossly out of proportion to the services received (p. 471). In other words, Moore wants to understand what makes the exchange seem equitable. He admits that the answers to such questions must always have a substantial margin of uncertainty while insisting that they also have a common objective core (p. 471). Better to accept the difficulty of researchable questions than to impose a definite answer full of unstated presuppositions or simply to throw up ones hands.

The working concept of exploitation that results may seem messy to some, but it is as precise as yet possible in a comparative inquiry about modernity and its dynamics. Moores definition of exploitation provides a powerful optic for understanding the decline of aristocratic authority. Meanwhile, his willingness to share the thought process behind his judgments is both large spirited and disarming. If a reader is dissatisfied, she is invited to pursue the quest further. Truth is a cooperative project. Moore credits the scholars from whom he has learned and he challenges the reader to build and transcend his work as well.

There is a deep skepticism and pessimism to Moores view of what modernization costs. In contrast to those who would treat German and Japanese fascism (revolution from above) as a moment that ended with World War II, Moore finds a pattern of fascist, militarist success whenever a traditional state is strong and commercialized agriculture is weak. Perhaps fascism is not quite modern and far from dead.

In contrast to those who would simply celebrate democratic victories, Moore takes a somewhat darker view of the rise of the liberal democratic system in England, France, and the United States. His awareness of the price of progress is apparent in the title Moore gives to his opening chapter on England: England and the Contributions of Violence to Gradualism. For Moore, the establishment of democratic institutions has depended on the elimination of the peasant problem. That is, democratic progress has always been predicated on the enormous suffering entailed in such processes as the Enclosure Acts and the Highland Clearances. Contrary to the popular Anglo-American historical account (short version!), which emphasizes a relatively sedate, peaceful process of democratic institution building stretching back to at least the Magna Carta, and perhaps to Athens, Moore directs attention to the cost of modern achievements. He does not doubt that democratic freedom is a cherished achievement. But, he writes, That the violence and coercion [primarily, but not only, of the enclosures] which produced these results took place over a long space of time... must not blind us to the fact that it was massive violence exercised by the upper classes against the lower (p. 29). Moore would have us confront truth in all its painful complexity. Those who simply celebrate democracy may obscure unhappy consequences that, were they clear, perhaps could be avoided or attenuated. As he subsequently put it, Under close examination no political system turns out to be edifying.

Progress, Moore finds, has invariably and inevitably required a huge measure of human suffering. If this continues to be the caseand it is difficult to see why that nasty reality should suddenly disappearthen one must be wary of those who promise paradise from market economics plus parliamentarianism, and one must instead ask who is bearing which burdens in any transition.

What Moore teaches best is not a matter of particular facts. (Most historians believe he overstates the victims of enclosures.) What he teaches is a way to ask questions so as to make the most informed moral judgments and choices.

Moore does not take for granted the persistence of any social and political arrangements. Instead, he believes the costs of the status quo must always be weighed against the costs of changing it.

The assumption of inertia, that cultural and social continuity do not require explanation, obliterates the fact that both have to be recreated anew in each generation, often with great pain and suffering. To maintain and transmit a value system, human beings are punched, bullied, sent to jail, thrown into concentration camps, cajoled, bribed, made into heroes, encouraged to read newspapers, stood up against a wall and shot, and sometimes even taught sociology. (p. 486)