Sarah Kovner - Prisoners of the Empire

Here you can read online Sarah Kovner - Prisoners of the Empire full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Harvard University Press, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Prisoners of the Empire

- Author:

- Publisher:Harvard University Press

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Prisoners of the Empire: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Prisoners of the Empire" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Prisoners of the Empire — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Prisoners of the Empire" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

PRISONERS of the EMPIRE

Inside Japanese POW Camps

Sarah Kovner

Cambridge, Massachusetts | London, England 2020

For Lily

Copyright 2020 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Cover photos: (top) Myanmar, Soft_Light/Getty Images Plus; (bottom) Prisoners in Bataan, 1942, photo by Keystone/Stringer/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Cover design: Jill Breitbarth

978-0-674-25019-2 (EPUB)

978-0-674-25020-8 (MOBI)

978-0-674-25021-5 (PDF)

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN: 978-0-674-73761-7 (alk. paper)

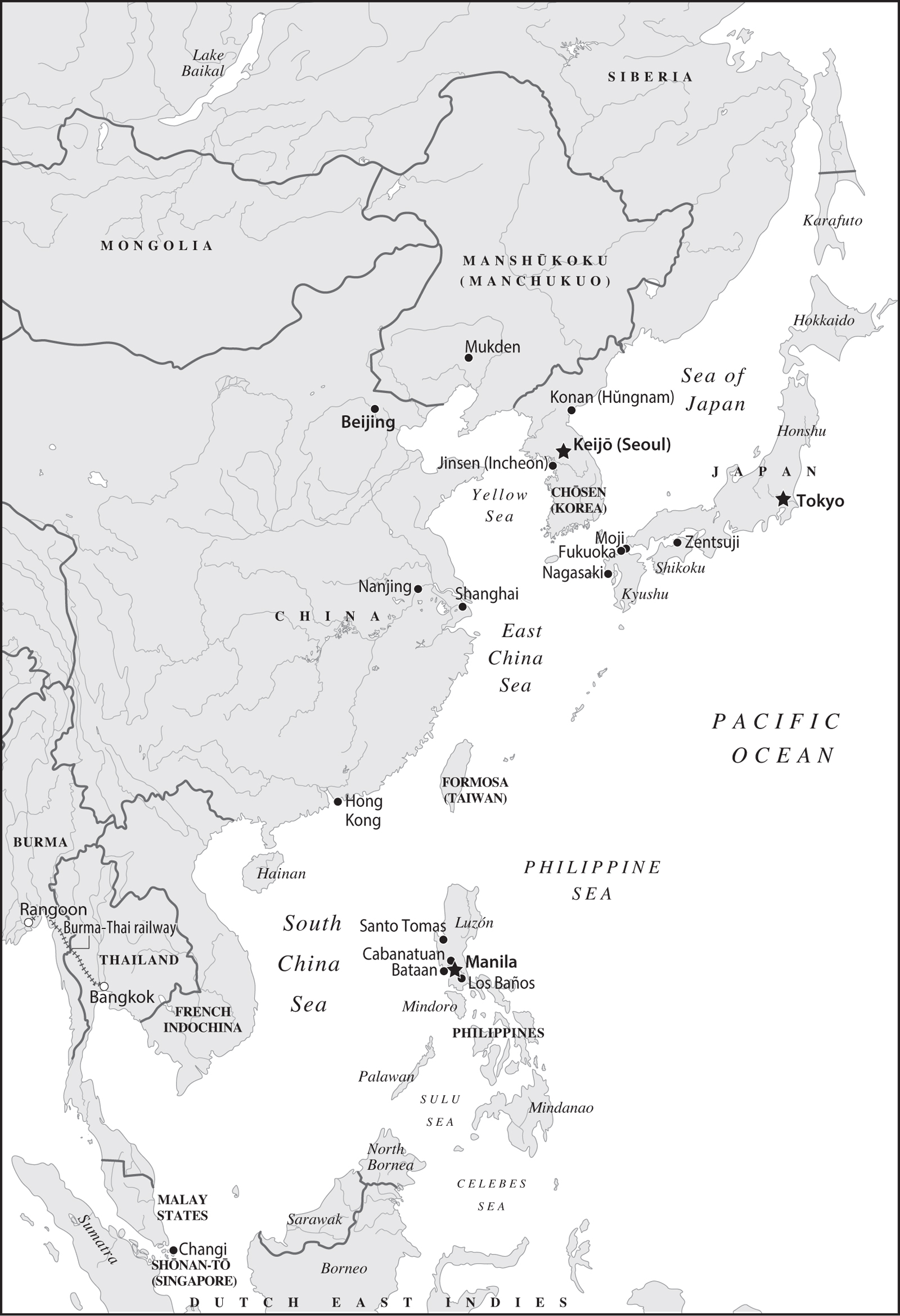

Japanese Empire with discussed camps and capitals.

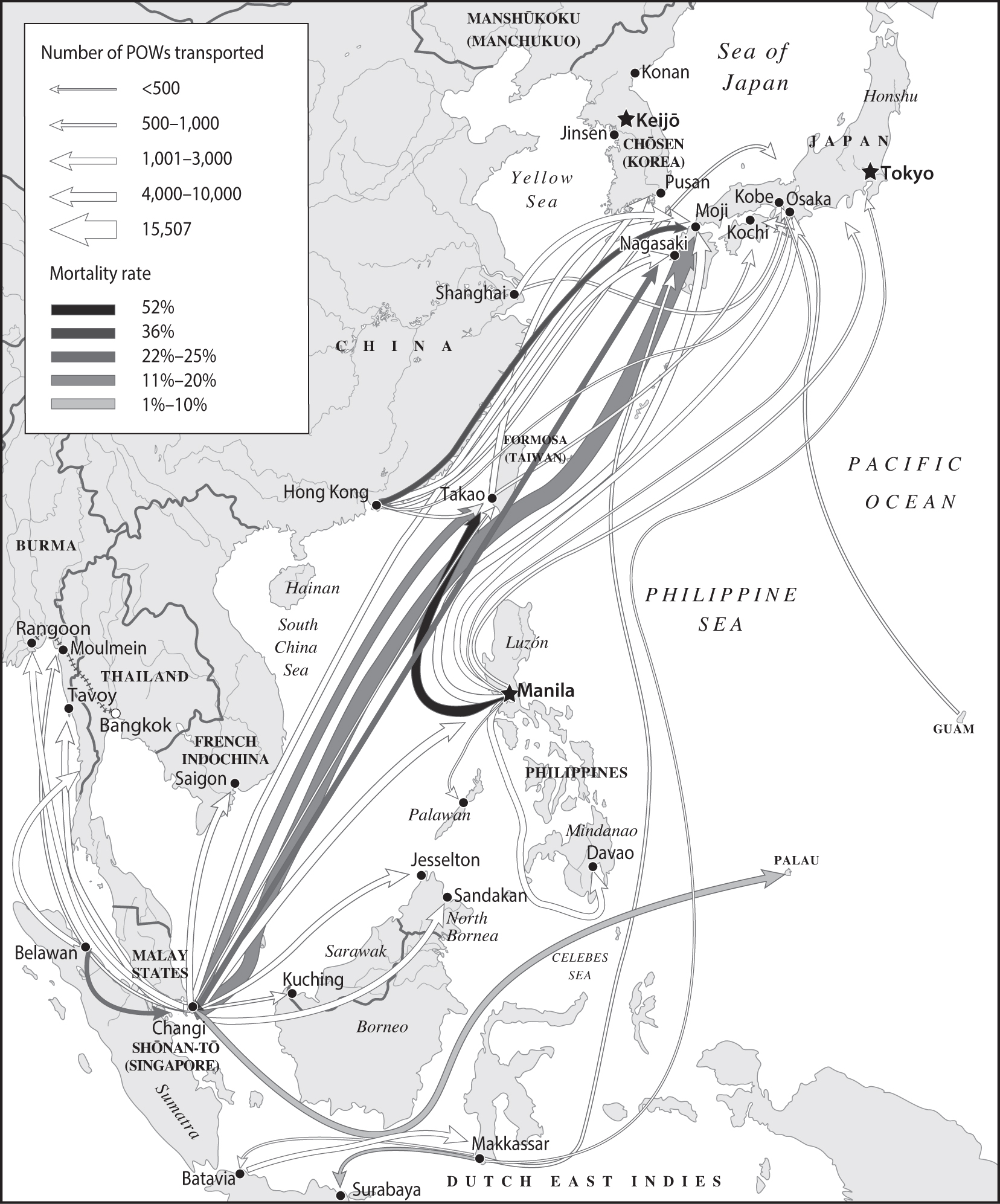

Transporting POWs across vast expanses.

In two days in December 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy and Army shocked the world with attacks on Pearl Harbor, Malaya, and Thailand. Japan invaded China in mid-1937, and careful observers had predicted Japanese military action. Yet most people in the United States and Britain were taken completely by surprise. In those days before email and free phone calls, before direct flights to Tokyo and Thailand, any threat from Japan seemed impossibly far away. But now Japanese forces rapidly advanced across thousands of miles of open ocean, from the Aleutians to the straits of Malacca, from the Marshall Islands to the Burma Road. In the first five months of the Pacific War, they took as prisoners more than 140,000 Allied servicemen and 130,000 civilians from a dozen countries. Japanese commanders hastily set up hundreds of POW camps and civilian internment centers. Of the American POWs, one in three did not survive the war. And by the wars end, more Australians had died in captivity than in combat. Once far away, Japan and the Japanese became all too familiar to Western countries, above all as objects of hatred.

Ever since, memoirs, popular histories, and literary accounts have described how the Japanese systematically humiliated and abused their captives. Whether the tragic Lieutenant Colonel Nicholson in the 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai, or the heroic army airman Louis Zamperini in Laura Hillenbrands best-selling book Unbroken, POWs are portrayed as martyrs to the unmitigated cruelty of their guards and camp commanders. These accounts often present Japanese behavior as simply inexplicable. When they do offer an explanation for the harsh treatment of POWs, they often attribute it to Japanese military education and the bushid codea military ideology once applied to samurai, and revived and refigured over the course of the early twentieth century. The Japanese military trained soldiers to feel extreme shame about being taken captive, and supposedly inculcated contempt against any enemy soldier who willingly surrendered.

Considering that POWs in the Pacific accounted for only about 0.5 percent of Allied servicemen, popular understanding of this history has had an outsized impact on memories of the war. Sixty-five years after World War II ended, Unbroken became one of the longest-running best sellers of all time. The suffering of POWs in the Pacific is so familiar in popular culture that it can be invoked and immediately recognized without any context or explanation, whether as background to a character in a John Grisham thriller, or as the beginningin media resof Call of Duty: World at War, the blockbuster video game.

Yet there have always been aspects of the captivity experience that resisted easy explanation. When Japan and Russia went to war in 1904, the international press and Western observers praised Japans generous treatment of Russian POWs. Japans scrupulous conduct forced Western powers to redefine international law as universal, rather than as the custom of Christian civilization. In World War II, many guards were not Japanese soldiers at all, but gunzokuKorean and Taiwanese civilian employees. And even if Japanese notions of military honor could account for the treatment of Allied POWs, how could they explain the experience of civilian internees? This experience was different from what POWs endured, but was also difficult. Some men and women were even held in the same camps as POWs. This too has shaped how people remember the Pacific War, such as in the J. G. Ballard book (and Steven Spielberg film) Empire of the Sun, and the many other accounts of Europeans, Americans, and Australians rounded up in places like Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Manila. Finally, how do we explain why the suffering and death of Allied POWs became infamous in the United States and the British Commonwealth, while it hardly figures in Japanese popular memories of the Pacific War?

These questions call out for a comparative analysis. But English-language accounts usually lack an international perspective. Americans study Americans, and Australians study Australians. Very few even cite Japanese sources. These accounts seldom mention Japanese and Japanese-American internees in the United States. Yet while the war was still being fought, the government in Tokyo focused on how the United States treated these civilian internees, and this treatment influenced how the Japanese handled Allied POWs. Finally, when assessing Japanese conduct, such as the execution of captured airmen, should we not compare it to Allied actions that Tokyo considered war crimes, such as the firebombing of Japanese cities?

English-language accounts also tend to underplay the large proportion of POW deaths that resulted from friendly fire, such as air and submarine attacks on Japanese convoys and bombing raids on Japanese cities, which Allied commanders carried out even when they knew they would likely kill POWs. It has been argued that more POWs died from friendly fire than from Japanese abuse and neglect.

In this book I argue that there was nothing inherent to Japanese character or culture that led to the inhumane treatment of POWs. Rather than accepting as a given that Japanese society included a code of conduct that required inflicting cruelty on hundreds of thousands of captives, I will show that senior officials gave much less thought to their management than todays accounts assume. Far more people surrendered than commanders had anticipated. Pushed to their logistical limits, and fighting armies that were sometimes twice their size, Japanese commanders did not necessarily consider the care and feeding of captives a priority. It was Japanese inattention to the challenge of managing POWs, and lack of interest in caring for them, that led to many of the cruel and inhumane situations. But what stands out in the Japanese militarys approach to POWs is its unwitting cruelty. Clearly, many POWs suffered and died because of abuse or negligence, including forced labor, malnutrition, and poor medical care. But accounts that ignore the Japanese side of the story cannot begin to explain why.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Prisoners of the Empire»

Look at similar books to Prisoners of the Empire. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Prisoners of the Empire and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.