A CULTURAL HISTORY

OF HAIR

VOLUME 5

A Cultural History of Hair

General Editor: Geraldine Biddle-Perry

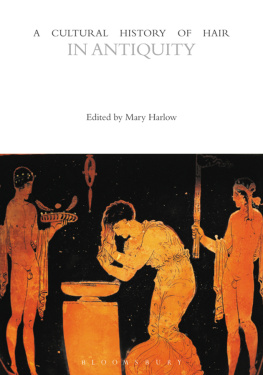

Volume 1

A Cultural History of Hair in Antiquity

Edited by Mary Harlow

Volume 2

A Cultural History of Hair in the Middle Ages

Edited by Roberta Milliken

Volume 3

A Cultural History of Hair in the Renaissance

Edited by Edith Snook

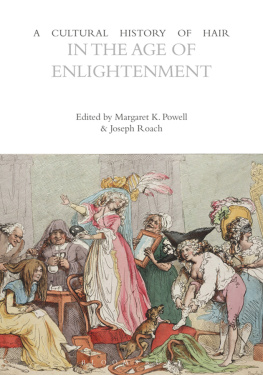

Volume 4

A Cultural History of Hair in the Age of Enlightenment

Edited by Margaret K. Powell and Joseph Roach

Volume 5

A Cultural History of Hair in the Age of Empire

Edited by Sarah Heaton

Volume 6

A Cultural History of Hair in the Modern Age

Edited by Geraldine Biddle-Perry

A Cultural History of Hair offers an unparalleled examination of the most malleable part of the human body. This fascinating set explores hairs intrinsic relationship to the construction and organization of diverse social bodies and strategies of identification throughout history. The six illustrated volumes, edited by leading specialists in the field, evidence the significance of human hair on the head and face and its styling, dressing, and management across the following historical periods: Antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Age of Enlightenment, the Age of Empire, and the Modern Age.

Using an innovative range of historical and theoretical sources, each volume is organized around the same key themes: religion and ritualized belief, self and societal identification, fashion and adornment, production and practice, health and hygiene, gender and sexuality, race and ethnicity, class and social status, representation. The aim is to offer readers a comprehensive account of human hair-related beliefs and practices in any given period and through time. It is not an encyclopedia. A Cultural History of Hair is an interdisciplinary collection of complex ideas and debates brought together in the work of an international range of scholars.

Geraldine Biddle-Perry

SARAH HEATON

Once one starts thinking about hair in the Age of Empire it appears everywhere. At a friends house during dinner, when asked what I was currently working on, I mentioned this book. My host went to the family safe and brought an old wooden box to the table which opened to reveal a long thick brown plait of Victorian hair. Perhaps I should have expected this, after all this is a house where tales of Tennyson and Barbara Villiers, mistress of King Charles II, vibrate through the walls. This was a girl who had taken over the Palmer Estates at seventeen when her mother died and her fathers mental health was in decline. Bored and lonely she wrote diaries and determined to marry for love. Yet she was beautiful and intelligent, and for a family who had fallen out of societys favor she was seen as capital and paraded first by her mother, and then her aunts, around debutante balls and society events. Hating it all she took her father out to the Crimea via land. She was not a woman who would sail to Constantinople and keep a safe distance from the action; this was a woman of the empire; she watched battles and met her husband Archibald Peel on Lord Raglans yacht. While it is thought she died in childbirth aged thirty-four in 1860 her hair has been carefully preserved and has lain quietly in the dark recess of the house. As an object it is unclear what is to be done with it but it certainly cannot be thrown out. Holding the hair of a Victorian woman who ran an estate, wrote, traveled, and married for love is extraordinarily compelling not simply because it takes you to another time and place but because it resonates so powerfully through all the lives which it has touched. Here is not simply the cold dark patina on an object once held, nor the sweat stains on a dress once worn but part of the woman herself: the hair which she touched as she wrote her diaries, which she styled in the Crimea, which was caressed by her husband and held by her children. This piece of hair, along with all those in this volume, continue to have afterlives which resonate through all those who encounter its strands. Perhaps understanding this the Victorians embraced hair in all its forms from long luxurious locks to intricate pieces of jewelry made from human hair and the hair of the dead. This fascination was by no means the preserve of the Victorians but part of a tangle of tresses that reached across the empire and beyond.

The concept of the West then is less a geographical demarcation than a historical one suggesting capitalist dominance in the new global economy. Although different cultures have their own hair practices there is, during the period, a colonizing impulse which extends to the economies of hair and its fashioning. Whether the empire is seen as a geographical, historical, or cultural construct, arguably it is the Victorians obsession with hair which fueled the global reach of hair in the Age of Empire and it is the Victorian obsession which the volume returns to again and again.

AFTERLIVES AND THE APOCRYPHAL

In contemporary culture we may not wear our deceaseds hair as jewelry but the habit of cutting a babys lock is common. We are also fascinated by the pieces of Victorian hair jewelry and macabre hair art which turn up on the UK television program Antiques Roadshow, and will happily peer at these objects from behind the safety of the glass cabinet in museums such as the Victoria and Albert in London. Fragments of Charles Darwins beard, apparently collected from his desk, are displayed in the Natural History Museum and a recent exhibition titled Curious Objects at Cambridge University included beard and scalp hair sent to Darwin in an attempt to refute his theories in The Descent of Man. There is also, perhaps predictably, Victorian hair for sale on eBay. Meanwhile, famous hair often makes the news; recently yet another locket purportedly containing a lock of Napoleons hair made the headlines. This one was discovered in a terraced house in Surrey, England, and went to auction in July 2015 fetching 7,500. The book brings to life the journey of a piece of hair across nearly 200 years until it was finally DNA tested by Guevara in 1994.

This sense of living on is apparently literalized even more compellingly in Lizzie Siddals hair. Married to Dante Gabriel Rossetti she was a model, artist, and poet, painted time and again by the Pre-Raphaelites. Of course her hair lives on in Rossettis paintings The article also notes that a bottle of their tonic was recently for sale on eBay for $249.99 rather than the $9.99 advertised back in 1901.

It is not just head hair which has afterlives. The story of one of the most famous locks of Victorian hair which lives on is the lock that Lady Caroline Lamb gave to Lord Byron. Credited with giving Byron the aphorism mad, bad and dangerous to know she is said to have sent him a snippet of her pubic hair; apocryphal the tale and the quotation may or may not be, but it lives on in our cultural consumption of Victorian hair. She finally married and had eight children with the Pre-Raphaelite Sir John Everett Millais who, like his contemporaries, was known for his painting of luxurious hair. Perhaps if the Pre-Raphaelites had at an earlier date paid such detailed attention to all of a womans hair rather than focusing on her head the apparent shock Ruskin felt may not have left him seemingly impotent. A glance through paintings from Walter Cranes