A CULTURAL HISTORY

OF HAIR

VOLUME 4

A Cultural History of Hair

General Editor: Geraldine Biddle-Perry

Volume 1

A Cultural History of Hair in Antiquity

Edited by Mary Harlow

Volume 2

A Cultural History of Hair in the Middle Ages

Edited by Roberta Milliken

Volume 3

A Cultural History of Hair in the Renaissance

Edited by Edith Snook

Volume 4

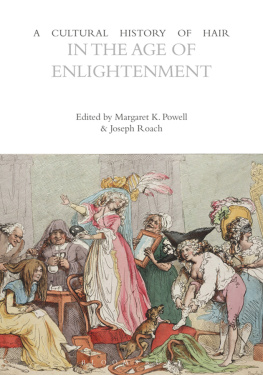

A Cultural History of Hair in the Age of Enlightenment

Edited by Margaret K. Powell and Joseph Roach

Volume 5

A Cultural History of Hair in the Age of Empire

Edited by Sarah Heaton

Volume 6

A Cultural History of Hair in the Modern Age

Edited by Geraldine Biddle-Perry

A CULTURAL HISTORY

OF HAIR

IN THE AGE OF

ENLIGHTENMENT

VOLUME 4

Edited by

Margaret K. Powell and Joseph Roach

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

A Cultural History of Hair offers an unparalleled examination of the most malleable part of the human body. This fascinating set explores hairs intrinsic relationship to the construction and organization of diverse social bodies and strategies of identification throughout history. The six illustrated volumes, edited by leading specialists in the field, evidence the significance of human hair on the head and face and its styling, dressing, and management across the following historical periods: antiquity, the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Age of Enlightenment, the Age of Empire, and the Modern Age.

Using an innovative range of historical and theoretical sources, each volume is organized around the same key themes: religion and ritualized belief, self and societal identification, fashion and adornment, production and practice, health and hygiene, gender and sexuality, race and ethnicity, class and social status, representation. The aim is to offer readers a comprehensive account of human hair-related beliefs and practices in any given period and through time. It is not an encyclopedia. A Cultural History of Hair is an interdisciplinary collection of complex ideas and debates brought together in the work of an international range of scholars.

Geraldine Biddle-Perry

The Editors wish to offer special thanks to the Lewis Walpole Library (LWL) of Farmington, Connecticut, for providing images free of charge, and to the LWL staff, especially Susan Walker and Kristen McDonald, who promptly and patiently answered every request. We are also grateful to the staffs of the Yale Center for British Art and the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, especially Anne Marie Menta, for their kind assistance. We thank the editors and staff at Bloomsbury, including Anna Wright, Pari Thompson, Yvonne Thouroude, and Katherine Bosiacki, for their attentive help. Frances Arnold, Editorial Director for Visual Arts, and Geraldine Biddle-Perry, Series Editor, have kept faith with the project from the beginning, and we are grateful for their expert guidance. We thank Janice Carlisle for her help in preparing the Bibliography.

MARGARET K. POWELL AND JOSEPH ROACH

What is Enlightenment? To this question the philosopher Immanuel Kant famously answered: Enlightenment is people daring to be wise. By that he meant people having the maturity and courage to think for themselves as individuals, living in a society that allows others to do the same. Kants definition of Enlightenment is both affirmed and contradicted by the cultural history of hair, 16501800, the period known by scholars today as the long eighteenth century. On the one hand, by the time Kant wrote in 1784, empiricism, or proof by scientific experiment rather than by appeal to traditional authorities or received ideas, had firmly established itself in philosophical theory and laboratory practice. Over a century earlier it had already inspired the motto of the Royal Society (founded in 1660): nullius in verba, or dont take anybodys word for it. On the other hand, irrational behavior about hair, along with hair itself, simultaneously reached all-time highs. The Enlightenment saw the most extravagant developments of hair fashion in any period of history, including the proliferation of wigs for men and fantastic hairdos for women (). The popularity of these extravagancies proved that many people were anxious to express themselves by means of their hair without necessarily bothering to think things through for themselves before doing so. Although the laws of fashion may seem to operate as inevitably as the physical laws of nature, they always depend on the word of someone, real or imagined, to exert the gravitational forces of emulation, discrimination, and discipline. In the chapters that follow, the contributors understand hair in the Enlightenment, also known as The Age of Reason, as both a material fact of nature and social magic.

Under the sway of empiricism, enlightened science looked at hair objectively, literally putting it under the microscope, itself a recent invention. In 1665 Robert Hooke, Curator of Experiments for the Royal Society, published his meticulously illustrated Micrographia, featuring the magnified images of vermin, including one of a louse, itself covered with tiny hairs, grasping a strand of human hair with its well-adapted little claws (see

Meanwhile, the successes of empirical experimentation encouraged the growth of instrumental reason, the application of scientific discoveries to practical arts and trades. Modernizing specialists such as physicians, professional hairdressers, and manufacturers of woolen goods, for instance, applied the newly acquired knowledge to a range of innovations in medical treatment, hair care, and textile production. The number and prominence of hairdressers grew, and the increasing recognition of their technical expertise created a demand not only for primping but also for publication: while treatises, manuals, handbooks, and illustrative prints abounded, so did mocking poetry, prose, and graphic satires. Natural philosophers also applied scientific principles to great projects of classification, distributing hair along with all kinds of flora and fauna into detailed taxonomies. But even at its most instrumentally rational, hair research could revert to pseudoscience under the pressure of unexamined stereotypes and bigoted presuppositions. The classification of peoples by race, for instance, grew apace during the age of Enlightenment. Observable differences in the kinds of hair typical of people from different parts of the world morphed spuriously from demonstrable empirical fact into new superstitions about racial difference. Racist taxonomists went so far as to place some types of human hair into the category of animal wool. Less egregious but still dubious notions about the meaning of hair defined human persons on the bases of gendered identity and social class. Nor did religion abdicate to secular fashion all of its long-standing authority over hair.

The chapters in this volumecovering Religion and Ritualized Belief, Self and Society, Fashion and Adornment, Production and Practice, Health and Hygiene, Gender and Sexuality, Race and Ethnicity, Class and Social Status, and Cultural Representationsconcern themselves with the Enlightenment in Britain and some of its colonies. This focus honors the special expertise of the contributors and the precedents of their previous collaborations on the subject of hair in the long eighteenth century. Another ensemble of authors would have produced a different volume, but not, we believe, wholly different. They would have been obliged, as we have been, to treat the subject of hair seriously in light of its most important and representative meanings: spiritual, psychological, ornamental, commercial, medical, sexual, ethnic, social, cultural, and philosophical. Of course on numberless occasions in normal life, then as now, hair meant nothing at all; but these instances, available to be known by commonsense inference alone, obviously escaped documentation by historical records. What the records do show, as the contributions to this volume attest, is an increasingly robust preoccupation with hair over the course of the long eighteenth century. They show the norms and the deviations, the obsession and the neglect, the pleasures and the pains, and the artistry and the folly. In aggregate, they prove that hair, whatever its length, was big in the Enlightenment.