ART UNDER CONTROL

IN NORTH KOREA

ART UNDER CONTROL

IN NORTH KOREA

JANE PORTAL

REAKTION BOOKS

Published in Association with The British Museum Press

Dedicated to NJS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2005

Copyright Jane Portal, 2005

Published in association with The British Museum Press

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by C&C Offset Printing Co., Ltd

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Portal, Jane

Art under control in North Korea

1. Arts Korea (North) 2. Arts and state Korea (North)

3. Art and society Korea (North) 4. Socialist realism in art Korea (North)

I. Title

709.5'193

eISBN: 9781861898388

CONTENTS

1 Han Jun-bin, Were the Happiest in the World, 1975, ink on paper, 133 109 cm

ART FOR THE STATE

Realist art is the art of battle: it battles against false views of reality and impulses which subvert mans real interests. It makes correct views possible and reinforces productive impulses.

Bertolt Brecht

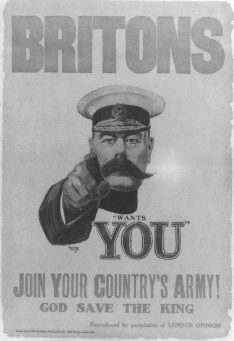

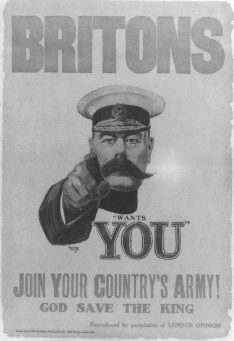

Nations have always requisitioned and utilized artworks. If anything, this process proliferated in the twentieth century, when art was widely adopted for propaganda purposes and those who produced it were strictly controlled by totalitarian states. It was the Soviet Union that initially kept the tightest control on cultural output and defined the needs of the state. The influence of both the Soviet Union and China was behind the development of Socialist Realist art in North Korea. In most circumstances, art for the state can be characterized as being essentially large-scale, dramatic and message-laden (illus. 2).

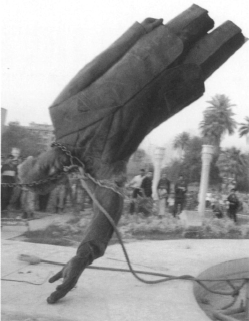

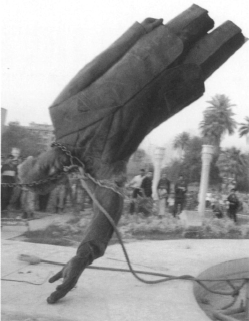

It is not only the production of artistic works that has been determined by totalitarian regimes. Control also extends to the destruction of works of art regarded as inappropriate. In Nazi Germany, art eschewed by the state, Entartete Art, was ridiculed and disposed of. Later in the century, hordes of marauding young Red Guards in the Chinese Cultural Revolution (196676) terrorized the population by bursting into their houses and smashing antiquities and family heirlooms in order to carry out Chairman Maos orders to destroy the Four Olds. In more recent decades a succession of images of deposed Communist autocrats have been destroyed after a change of regime, while in Budapest they have been collected in a park for unwanted state sculpture. The most dramatic recent instance of destruction is perhaps the blowing up by the Taliban of the large Buddha statues at Bamiyan in Afghanistan in 2001. The widely reported toppling of the statue of Saddam Hussein in Baghdad in 2003 demonstrates the tremendous impact that popular destruction of a work of art prescribed by the state can have (illus. 3).

2 Alfred Leete, Your Country Needs You!, 1914, design for a recruitment poster.

3 Saddam Hussein being toppled.

HISTORICAL PRECEDENTS

There are many historical precedents for the kind of buildings, monuments and works of art produced in North Korea under the Kim regime, some of which may have been known to the artists and policy-makers and some not. It is doubtful, for example, that Kim Il-sung (191294) would have been conscious of the fact that, when encouraging his subjects to think of North Korea as Paradise on earth (illus. 1), he was following in the footsteps of Augustus Caesar in the first century BC. It has been suggested that, by using a new visual imagery, Augustus created a new mythology of Rome:

Built on relatively simple foundations, the myth perpetuated itself and transcended the realities of everyday life to project onto future generations the impression that they lived in the best of all possible worlds in the best of all times.

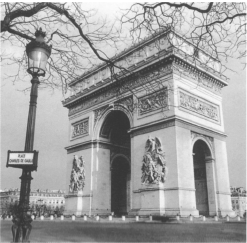

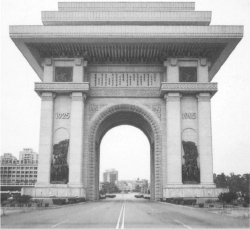

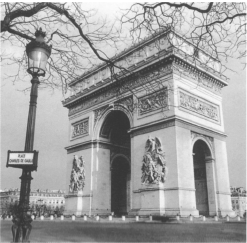

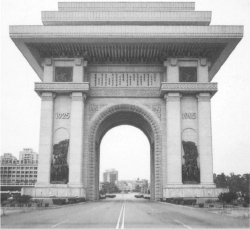

The Roman Empire was the major model for public art, and the use of the triumphal arch to demonstrate the glory and triumph of the regime dates from this time (illus. 4, 5 and 6).

4 G. B. Piranesi, Arch of Severus and Caracalla in the Roman Forum, 1756, etching.

5 Jean-Franois Chalgrin, Arc de Triomphe, Paris, 180636.

6 Mansudae Studio, Arch of Triumph, Pyongyang, 1982.

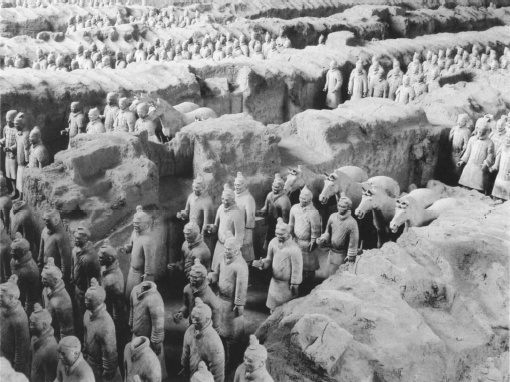

7 Pit containing thousands of terracotta warriors guarding the tomb of the first emperor of China, Qin Shihuangdi, who died in 221 BC, at Lintong outside Xian.

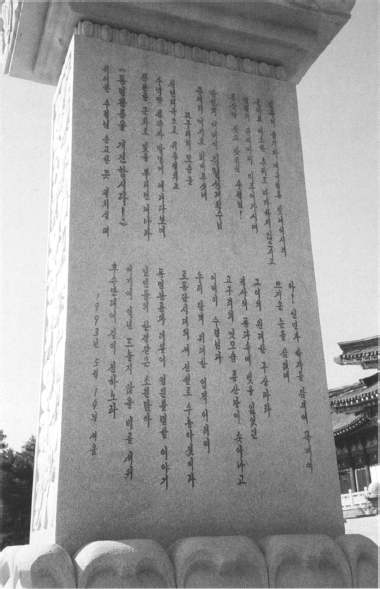

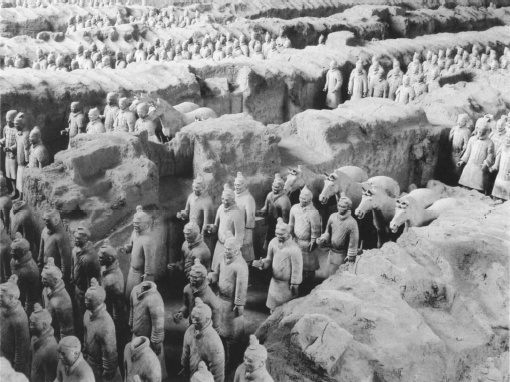

Kim is much more likely to have been aware of the first emperor of China, Qin Shihuangdi (256221 BC), who was notorious not only for unifying China, its currency, weights and measures and written script, but also for his burning of the books of Confucianism in his megalomaniac desire to control the hearts and minds of his subjects, both during his lifetime and after his death (illus. 7). Also like Kim, he travelled around his country erecting stelae marking the places he had visited and listing his achievements, as if to say, look at me and remember (illus. 8). For example, part of an inscription on a tower at Mount Langya reads:

Great are the Emperors achievements...

He works day and night without rest;

He defines the laws, leaving nothing in doubt,

Making known what is forbidden.

Kim would definitely have known of another great Chinese emperor, Qianlong (r. 173695), who also carried out what has been called a literary inquisition. Qianlongs confidence in the superiority of his empire over all outside it is also expressed in his rebuttal of George, 1st Earl Macartneys embassy in search of a trade agreement in 1793:

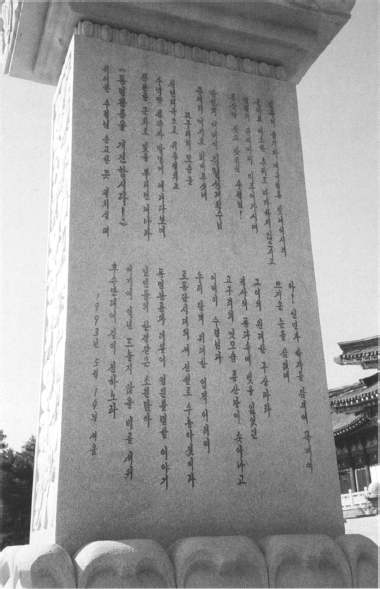

| 8 Kim ll-sungs calligraphy inscribed on a stone stele in front of the tomb at Chinpari, south-east of Pyongyang, said to be of Tongmyong, first king of the Koguryo Kingdom. The date of his birth is given as 298 BC in North Korea and 37 BC in South Korea. |