SLEEPWALKING INTO A NEW WORLD

THE LAWRENCE STONE LECTURES

Sponsored by

The Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies and Princeton University Press

2014

A list of titles in this series appears at the back of the book.

SLEEPWALKING INTO A NEW WORLD

THE EMERGENCE OF ITALIAN CITY COMMUNES IN THE TWELFTH CENTURY

CHRIS WICKHAM

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2015 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

Jacket phote: View of Pisa, detail from

Saint Nicholas of Tolentino and View of Pisa.

Photo Scala/Art Resource, NY.

Photograph of Lucca Cathedral labyrinth hayespdx.

Licensed under the Creative Commons

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/legalcode)

Cropped and colorized from original.

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 978-0-691-14828-1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014947305

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Adobe Jenson Pro and Trade Gothic LT Std

Printed on acid-free paper

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

COMMUNES

Chapter 2

MILAN

Chapter 3

PISA

Chapter 4

ROME

Chapter 5

ITALY

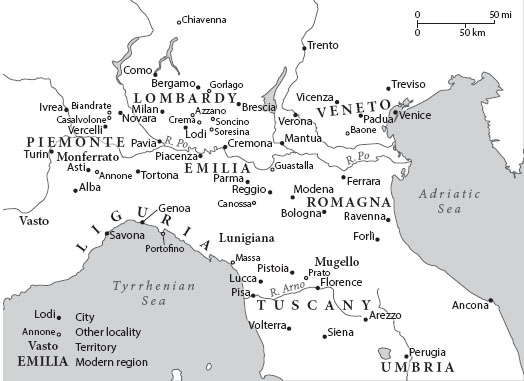

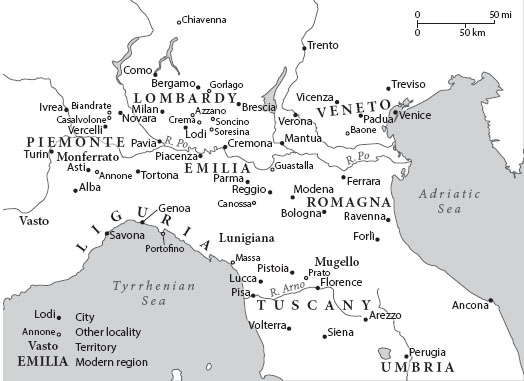

MAPS

Map 1

COMMUNAL ITALY

Map 2

MILAN

Map 3

THE TERRITORY OF MILAN

Map 4

PISA

Map 5

THE TERRITORY OF PISA

Map 6

ROME

Map 7

LAZIO

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am very grateful to Princeton University and Princeton University Press for inviting me to give the Lawrence Stone Lectures in May 2013, which were the basis for this book: and in particular to my hosts, Philip Nord and Brigitta van Rheinberg; to Peter Brown, Pat Geary, John Haldon, Bill Jordan, Helmut Reimitz, and Jack Tannous, who made the stay of myself and my wife Leslie Brubaker so welcoming; and to all of these for questions and critical commentary which greatly improved the subsequent book. I am also very grateful indeed to Eddie Coleman, who critiqued the whole text, Leslie Brubaker, who critiqued . Alessandra Mercantini, of the Archivio Doria Pamphilj in Rome, kindly made my consultation of a crucial cartulary easy. And I had essential help, in the form of advice and unpublished work, from other old friends, Maria Luisa Ceccarelli Lemut, Maria Elena Cortese, Alessio Fiore, Pino Petralia, Gigi Provero, Gianluca Raccagni, and Enrica Salvatori. As usual, without friends, whatever merits my book has would have been very much fewer.

Birmingham, October 2013

A NOTE ON PERSONAL NAMES

As elsewhere in my books on Italy, almost all personal names are here rendered into Italian, except for the names of popes and emperors, which I have put into English. But I have here also put Archdeacon Hildebrand and Matilda of Tuscany into English, on the grounds that these two are widely known in the English-speaking world under these names, and much less so as Ildebrando and Matilde.

1

COMMUNES

In 1117, after a great earthquake which devastated northern Italy, the archbishop of Milan and the consuls of the same citythe citys leaderscalled the people of other northern cities and their bishops to a great meeting in Milan, in the Broletto, an open space beside Milans two cathedrals, now part of the Piazza del Duomo. There, in the words of an eyewitness, the chronicler Landolfo of S. Paolo, writing two decades later:

The archbishop and the consuls set up two theatra [stages]; on one the archbishop with the bishops, abbots and leading churchmen stood and sat; in the other the consuls with men skilled in laws and customs. And all around them were present an innumerable multitude of clerics and the laity, including women and virgins, expecting the burial of vices and the revival of virtues.

It seems that this meeting was called in response to the earthquake, and Landolfo mentions shortly after the whole people congregated there out of fear of the ruin of the rubble, so that they could hear mass and preaching; it was also, however, seen as a moment in which people could ask for justice, and Landolfo himself was there to seek restitution, for he had recently been expelled from the church (S. Paolo) of which he was the priest and part owner. He failed in that; his enemy

This narrative can be set against a document from July of the same year, surviving in a contemporary copy, stating that in the public arengo [perhaps in the same open space] in which was lord Giordano, archbishop of Milan, and there with him his priests and clerics of the major and minor orders of the church of Milan, in the presence of the Milanese consuls and with them many of the capitanei and vavassores [the two orders of the Lombard military aristocracy] and populus, the consuls of Milan decided a court case brought there by the bishop of the neighbouring and now-subject city of Lodi. This is only the second text which mentions consuls in Milan at all, and the first in which the consuls are actually namednineteen of themand shown acting in a judicial role. Landolfos account and the consular document seem to refer, if not to the same assembly, at least to rapidly succeeding versions of the same occasion, and thus reinforce each other: the one showing a highly orchestrated event, the other showing its effective legal content. And they have also been seenand heavily emphasisedas a pair ever since modern historiography began to concern itself with the origins of Italian city communes, which in the case of Milan goes back to Giorgio Giulini in the 1760s: in this dramatic moment, we can see the consuls of Milan begin to take on their new and future role as urban rulers, and Italian history took a decisive new path from then on.

Map 1. Communal Italy

In what follows, I intend to nuance that moment, quite considerably. But let us begin by looking briefly at why the moment, and the new rgime, has such historiographical importance. There are two contexts for this, seen very broadly, one Italian and one international (including, not least, American). For professional historians in Italy, the role of the middle ages in the grand narrative of the past was never that of the origins of the modern state, as in most of western Europe (or else its regrettable failure in Germany), but, rather, the victory of the autonomous city states over external domination, which made possible the civic culture of the Renaissance; indeed, external rule was only part of it, for Italians tended until recently to regard the genuine state-building of Norman and Angevin southern Italy as a wasted opportunity

As for the international interest in the subject, this was associated, from Burckhardt through to US Western Civ, with the Renaissance too, although here also with the addition of the supposed democratic, or at least republican, nature of the Italian communes, as a contribution to the origins of modernity. As the historian of Venice Frederic C. Lane said to the American Historical Association in 1965, My thesis here is that republicanism, not capitalism, is the most distinctive and significant aspect of these Italian city-states; that republicanism gave to the civilization of Italy from the thirteenth through the sixteenth century its distinctive

Next page