For my grandfather, Francesco

Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

37 East 7th Street

New York, New York 10003

www.papress.com

2015 Francesco Spampinato

978-1-61689-268-5

All rights reserved

17 16 15 18 4 3 2 1 First edition

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Editors: Nicola Bednarek Brower, Jay Sacher, Barbara Darko

Design: Paul Wagner

Design Assistance: Benjamin English, Amrita Marino

Special thanks to: Meredith Baber, Sara Bader, Janet Behning, Megan Carey, Carina Cha, Andrea Chlad, Barbara Darko, Ali Dawes, Russell Fernandez, Will Foster, Jan Hartman, Jan Haux, Mia Johnson, Diane Levinson, Jennifer Lippert, Katharine Myers, Rob Shaeffer, Sara Stemen, Kaymar Thomas, Joseph Weston, and Janet Wong of Princeton Architectural Press Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Spampinato, Francesco, 1978

Come together : the rise of cooperative art and design /

Francesco Spampinato. First edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-61689-268-5 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-61689-393-4 (epub, mobi)

1. ArtistsInterviews. 2. Group work in art. 3. Arts, 21st century.

I. Title.

NX160.S635 2014

700.6dc23

2014006393

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FRONT MATTER

ARTISTS OR GROUP

BACK MATTER

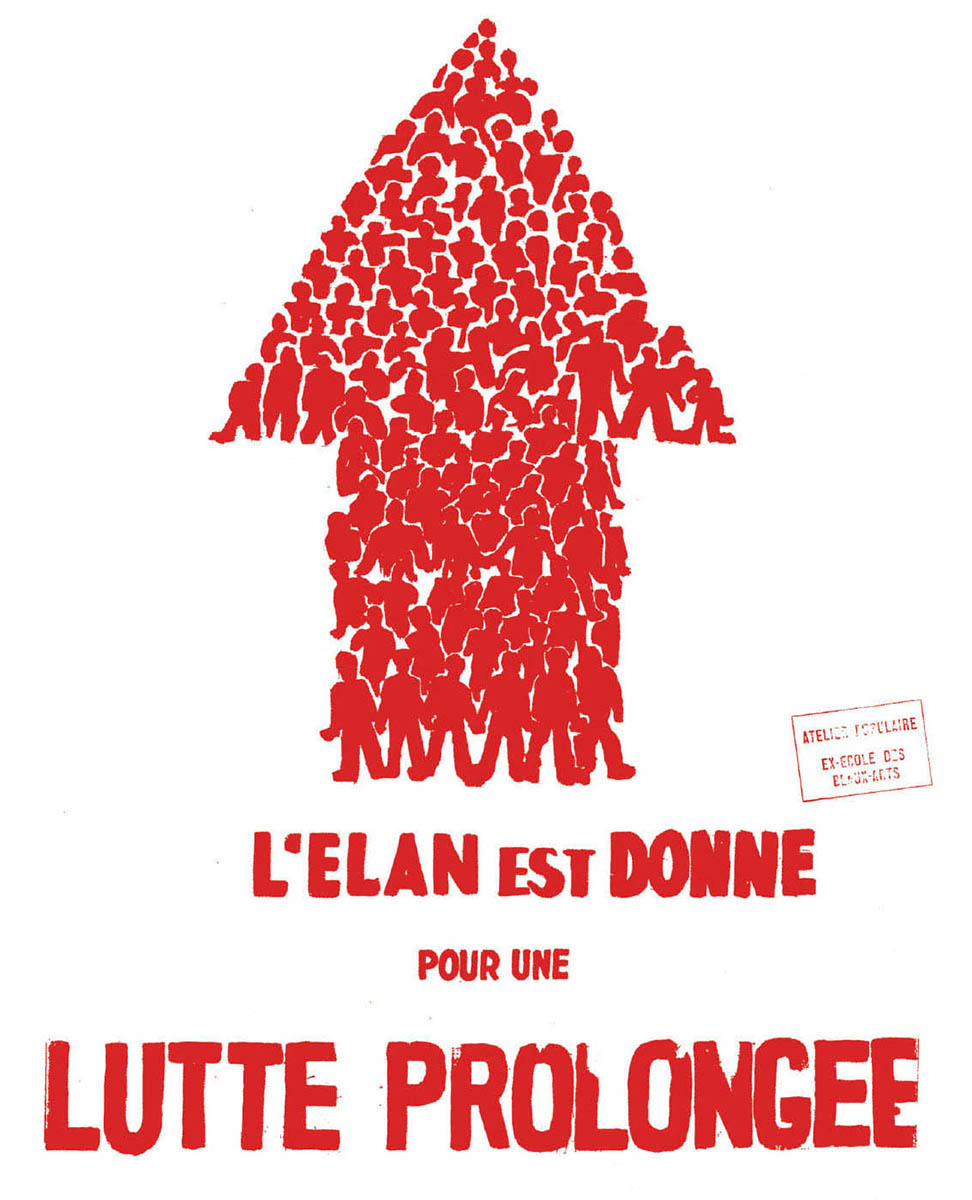

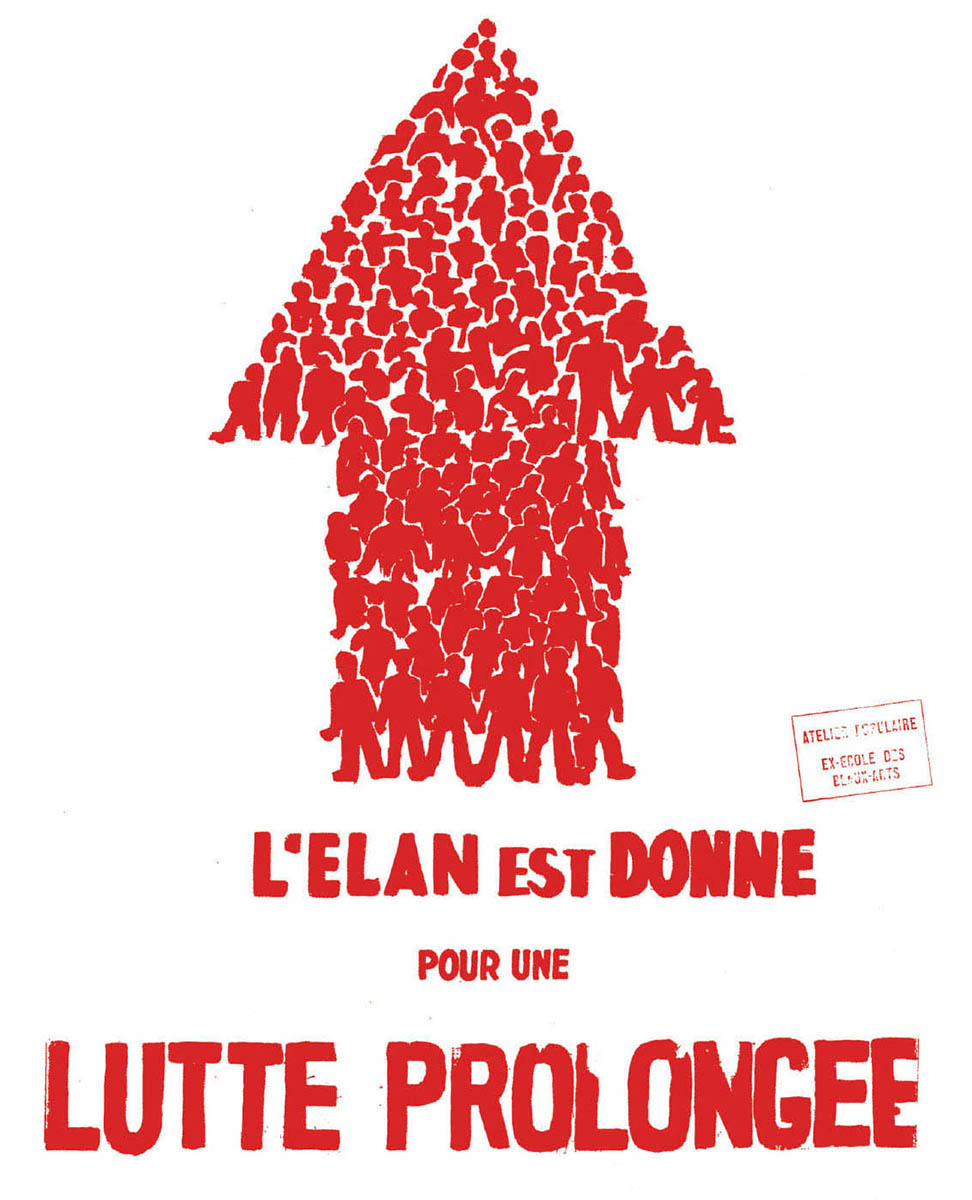

Fig. 1 Atelier Populaire, Spirits are high for a protracted struggle, poster, Paris, June 1968

INTRODUCTION

The Author Is Almost Dead

The role of the author is undergoing a massive transformation process. If, contrary to what Roland Barthes once famously wrote, the author is not dead, the idea of a sole creator working alone has certainly lost credibility and appeal. In its place new forms of cultural production are emerging: open, collective, horizontal, and participatory. Come Together: The Rise of Cooperative Art and Design presents some of the most representative art groups of the past few years and explores the mechanisms that lie behind the collective production of visual culture today.

The forty groups and duos featured in this book were invited to answer a series of questions about the motivations, logistics, and objectives that drive artists to give up their egos and embrace anonymous and shared operations. What emerges is a common desire to transform viewers into producers, making them aware of their potential as agents of change. Borrowing strategies and symbols from mass media, the global market, and the entertainment industry, these collectives unravel and overthrow social, political, and cultural power structures.

The notion of art produced by groups is as old as human history, but the origins of todays collective art date to the last centurys avant-garde movements such as Dadaism, futurism, Constructivism, Bauhaus, and situationism. Since the sixties, however, things have gotten more complicated. Over the decades, weve witnessed the rise of intellectual critiques of representation, ranging from postmodernism to relational aesthetics to the current postdigital generation. Concurrent with those trends in the art world, we have a series of social movements: 1968, the struggles against AIDS of the eighties, the antiglobalization movement of the late nineties, and the more recent Occupy! movement. Both of these spheres have turned out to be fruitful for collective operations.

The most representative collectives of the second half of the last century belong to the world of the visual arts (Art & Language, General Idea, Group Material), architecture (Archigram, Ant Farm), or graphic design (Atelier Populaire). [] But we find references to contemporary collectivism even in theater troupes (Bread and Puppet Theater), music bands (Destroy All Monsters, Laibach), pranksters (Provos, The Church of the SubGenius), and media activists (Raindance Corporation, Critical Art Ensemble), as well as in the arena of feminism (Guerrilla Girls), queer activism (Gran Fury), those struggling against the confines of cultural institutions (Art Workers Coalition), or those speaking to the issues of specific ethnic groups (Asco) or communities (WockenKlausur).

The Aesthetics of Conversation

The groups featured in this book are usually associated with the world of visual arts and design, but they are also involved in a variety of multidisciplinary activities. These can include everything from performance and publishing, to the organization of interventions and community projects that range from activism to curating to the creation of temporary spacesactual or virtualin which to experiment with new forms of cultural production.

Like those before them, these collectives are often born from preexisting communities, such as nonprofit organizations and squats, or other situations with common interests: theater, publishing, music, fashion, media. We will use the term art, in a broader sense, to refer to these various creative fields, as insisting on their separation has become increasingly outmoded.

While the collectives showcased are vastly different on the surface, they share several common characteristics, including how they use images. Rather than simply creating imagery to be contemplated by the viewer, collective art often uses imagery as a direct communication tool. Many, in fact, appropriate familiar signs and symbols from pop culture and mass media in an attempt to unravel the mechanisms of representation that lie at their root.

In general, a work of art from a contemporary collective is an invitation to engage in a conversation with the public. As Umberto Eco notes in Opera Aperta ,Every reception of a work of art is both an interpretation and a performance of it, because in every reception the work takes on a fresh perspective for itself.

The Group as Content

Another obvious common element in these collectives is the very fact that they work collectively, which is not only their modus operandi, but also often their message. On the model of past groups such as General Idea (19671994) and Art Club 2000 (19921993), these new collectives often produce self-portraits in parallel to their projects. These portraits work as promotional materials, but serve equally as well as a declaration of intent and a tool to interpret the groups activities.

The content of the activities of hobbypopMUSEUM, divided between Dsseldorf and London, is almost always subordinate to the form: the group. In the photos and videos that document their performances, we see them naked, covered with mud after a thermal treatment, or ranged around a white sofa, women sitting and men standing upright, wearing preppy clothing, with serious looks and heavily made-up faces. The images remind us of those of General Idea, who often portrayed themselves in ironic contexts, donning long poodle ears or posed under blankets with the wide-eyed innocence of babies ready to be fed. []

Many self-portraits of todays groups reflect on the tendency of youth to conform to the norms of their culture. Throughout their work, Berlin-based Discoteca Flaming Star and Reykjavik-based The Icelandic Love Corporation refer to music subcultures such as glam, folk, and metal. Not that they are interested in exploring content and lifestyles associated with them. They just borrow formal traits (costumes, symbols) and ritual aspects. Their performances, where music often has a crucial role, develop a direct and personal language with the public, within confined spaces and timelines, much like at an actual bands performance.

Next page