Sources of Indian Traditions

THIRD EDITION

VOLUME 2

MODERN INDIA, PAKISTAN, AND BANGLADESH

INTRODUCTION TO ASIAN CIVILIZATIONS

Introduction to Asian Civilizations

WM. THEODORE DE BARY, GENERAL EDITOR

Sources of Japanese Tradition,

1958; paperback ed., 2 vols., 1964 Second ed., vol. 1, 2001, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Donald Keene, George Tanabe, and Paul Varley; vol. 2, 2005, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Carol Gluck, and Arthur E. Tiedemann; vol. 2, abridged, 2 pts., 2006, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Carol Gluck, and Arthur E. Tiedemann

Sources of Indian Tradition,

1958; paperback ed., 2 vols., 1964 Second ed., vol. 1, 1988, edited and revised by Ainslee T. Embree; vol. 2, 1988, edited by Stephen Hay

Sources of Chinese Tradition,

1960, paperback ed., 2 vols., 1964 Second ed., vol. 1, 1999, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom; vol. 2, 2000, compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Richard Lufrano

Sources of Korean Tradition,

1997; 2 vols., vol. 1, 1997, compiled by Peter H. Lee and Wm. Theodore de Bary; vol. 2, 2001, compiled by Yngho Choe, Peter H. Lee, and Wm. Theodore de Bary

Sources of East Asian Tradition,

2008, 2 vols., edited by Wm. Theodore de Bary

Sources of Vietnamese Tradition,

2012, edited by Jayne Werner, John K. Whitmore, and George Dutton

Sources of Tibetan Tradition,

2013, edited by Kurtis R. Schaeffer, Matthew T. Kapstein, and Gray Tuttle

Sources of Indian Traditions

THIRD EDITION

VOLUME 2

MODERN INDIA, PAKISTAN, AND BANGLADESH

Edited by Rachel Fell McDermott, Leonard A. Gordon, Ainslie T. Embree, Frances W. Pritchett, and Dennis Dalton

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY PRESS

NEW YORK

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-51092-9

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sources of Indian tradition / edited by Rachel Fell McDermott [et al.]. 3rd ed.

p. cm. (Introduction to Asian civilizations)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-13830-7 (v. 2 : cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-51092-9 (electronic)

1. IndiaCivilizationSources. 2. PakistanCivilizationSources. 3. BangladeshCivilizationSources. 4. IndiaHistorySources. 5. PakistanHistorySources. 6. BangladeshHistorySources. I. McDermott, Rachel Fell.

DS423.S64 2013

954dc23

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

2011038816

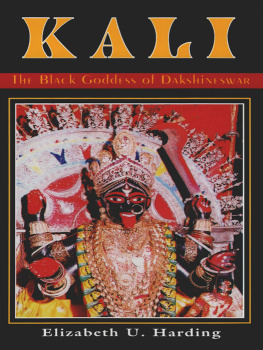

COVER ART: Album/Art Resource, NY

COVER DESIGN: Milenda Nan Ok Lee

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

CONTENTS

This third edition of the Sources of Indian Traditions represents a much greater departure from the second edition (published in 1988) than the second did from the first edition (published in 1958). When the second edition was initially undertaken, the ideological shifts in the study of South Asia that were brought about by postcolonial scholarship and the Subaltern Studies Collective, had not yet solidified. The second edition therefore updated the first by adding new translations, including some readings representing a non-Brahmanical standpoint, and by consulting American scholars of South Asia for input. No major rethinking of the organization of the two volumes was deemed necessary.

Since the late 1980s, mammoth changes in and enrichments of our understanding of South Asian history and historiography have occurredsome of which challenge the very conception of a sourcebook itself, for its privileging of certain viewpoints, assuming the primacy of texts (often religious), and perforce omitting considerations of historical context. Further criticisms of the second edition of the Sources included its implied divide between the premodern and the modern, mirrored in the distinction between the two volumes, such that religion was made to represent the premodern and politics the modern; the limited nature of some of the selections; the overrepresentation of some traditions; the underrepresentation of women, Dalits, and other marginalized voices throughout; the lack of attention to texts on ritual and pilgrimage, and the omission of sources on art, aesthetics, and scientific analysis; the lack of sufficient sources from a variety of non-Sanskritic texts; the presentation of traditions as if they were static, fixed entities, with a lack of attention given to overlapping interests, conflicts, and debates; the separating of Hindus from Muslims in both volumes, implying a Muslim period; the lack of documents such as council reforms, party platforms, and court cases; and the fact that the volumes stopped in the mid-1980s, without mention of Bangladesh or of all the postcolonial challenges and issues that inform the contemporary study of South Asia.

Despite these criticisms, the continued usage over the past thirty years of the Sources shows that there is nothing quite like them on the market. Instead of jettisoning the Sources, therefore, the five members of the editorial board for volume 2 of this third edition have undertaken a complete conceptual revision, rather than just an update along the lines established in the first and second editions. Nevertheless, as a team we are committed to the original vision of the Sources, as outlined in the preface to the first edition, according to which the source readings that are chosen tell us what the peoples of India have thought about the world they lived in and the problems they faced living together. [This book] is meant to provide the general reader with an understanding of the intellectual and spiritual traditions, [as well as] the political, economic, and social thought which other surveys have generally omitted.

We followed five working principles in our revision for the third edition. We resolved to write introductions to each section that would be cognizant and reflective of recent changes in historiography and interpretation; to aim throughout for a combination of thematic, synthetic ordering and a rough chronological sequencing of chapters (the latter being retained for its usefulness in teaching); to restrict ourselves, for reasons of space, to textual materials rather than attempting to encompass or represent the arts, and to forego the temptation to include examples of South Asian transnationalism; to begin volume 2 in 1707, with the death of Aurangzeb, and to conclude it at the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, three hundred years later; and to rename the volumes