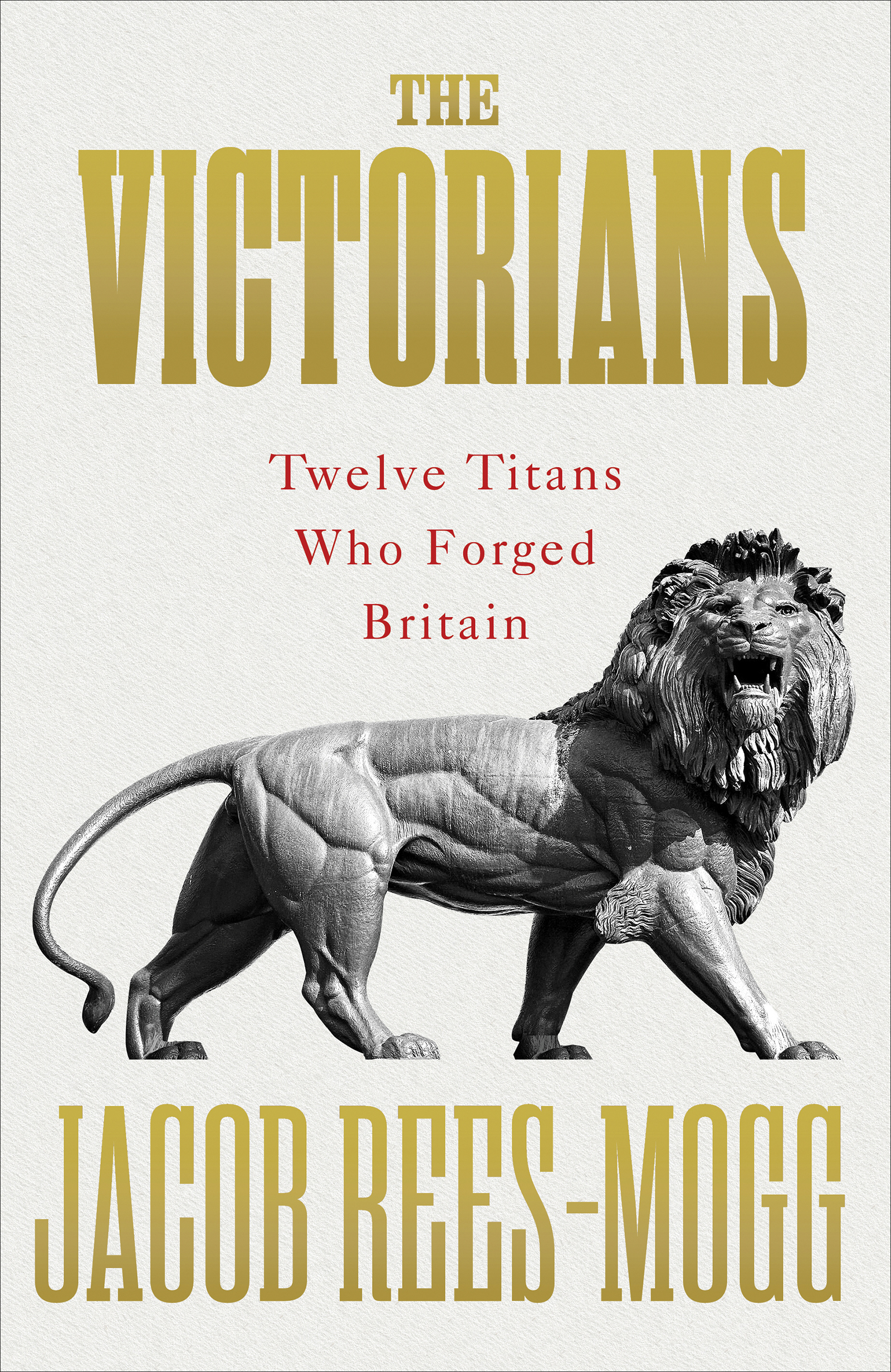

Jacob Rees-Mogg

THE VICTORIANS

Twelve Titans Who Forged Britain

Contents

About the Author

Jacob Rees-Mogg is a Conservative and the MP for the constituency of North East Somerset. Jacob sits on the Brexit Select Committee and he chairs the European Research Group. After Eton, Jacob read History at Trinity College, Oxford, before moving into finance. He co-founded Somerset Capital Management, which specialises in emerging markets investment management.

My mother on her 80th birthday, without whom this book could not have been written.

Introduction: The Eminent Victorians

Early in 1895, Queen Victorias private secretary Sir Henry Ponsonby attended on Her Majesty for the last time. Ponsonby had served the Queen in this role since 1870 but he had suffered a stroke in the previous year. He was no longer able to fulfil his duties and now he was calling on the Queen at Osborne to say his farewells. It is recorded that he looked at Victoria and said slowly, What a funny little old woman you are. The Queens response was Sir Henry, you cannot be well and she swiftly rang the bell for him to be removed from the Royal presence.

In a peculiar way, this unorthodox comment issued by a loyal courtier has become something of the standard view of the entire Victorian age. It is a very strange view or summation of a time of truly transformational, revolutionary change in Britain, an age when life expectancy was increasing, material wealth rising year by year and the Constitution evolving gloriously into a settled and stable state. All of it reduced to the figure of this littlest of little old ladies, of rather an excessive fusspot, who is never amused. At a stroke, the gilding of the Victorian period becomes scraped and damaged.

In his famous book Eminent Victorians, published in 1918, the Bloomsburyite Lytton Strachey did his bit to scratch at this gilding. His book took a blow torch to the heroes of the British nineteenth century while the abiding cynicism of our age has tended to accept his assessment. This too seems counter-intuitive because the briefest glance at the history of Victorian Britain reveals its abiding achievements and the parade of significant public figures from whom so much can be learned. Sadly, society these days, which has so little faith in anything, is understandably nervous of those Victorians who believed in so much, who embraced a sense of purpose and destiny so glaringly lacking both in their Hanoverian predecessors and in the beau monde of our contemporary world. In Eminent Victorians, Strachey mocked the weaknesses where they could be found but ignored the great image, whose brightness was excellent This images head was of fine gold, his breast and his arms of silver, his belly and thighs of brass. Such beautiful and resonant language comes from the Book of Daniel, as it described a glorious and gleaming figure. Only its feet were wrought of clay. Yet Strachey focused on the clay alone.

Perhaps it is natural to mock the recent past. We do so in order to ignore the failures of our own world so it is little surprise that the twentieth century should laugh at the Victorians. The twentieth century was a new age when, as Bloomsbury promised, tea would be taken at different and exciting times of the day but it was a period which embraced war and destruction on a scale unprecedented in world history. No wonder the new century should seek instead to laugh at the era just passed while a century of growing cynicism and of decline should glance enviously back to a period of moral certainty, of success. It could hardly have been any other way.

Nonetheless, I owe a debt to Strachey and his mean-minded book because when I had leafed through Eminent Victorians I was struck by its unfairness and its cynicism. It occurred to me that it was time to look again at some of these eminent Victorians and to reassess their effect upon and contribution to their world and to our own. Now is the time to reconsider and marvel at how remarkable the Victorian period was and to study the luminaries who led it and who invested in the condition of the people. After all, good leadership matters. Historians quarrel about the importance of individuals in the development of history and argue about how much would have happened anyway. However, the drive and industry of certain people cannot be ignored and the effects of their lives and their decisions can in fact be discerned and something of their impact glimpsed. Indeed, such was the quality of leadership in Victorias reign that it is more difficult to decide whom to exclude than to include as so many figures dominated their own fields. It is thus a reasonable complaint to say that any selection is essentially arbitrary.

Hence I have chosen a dozen such leaders in this book. A dozen who share certain common characteristics but who would not by any means have agreed with each other on everything. They come from throughout the long Victorian century, which stretches from the birth of Lord Palmerston in 1784 to the death of Albert Venn Dicey in 1922. Two elder statesmen, in the figures of Palmerston and Sir Robert Peel; two later, and rival, politicians, in the form of William Gladstone and Benjamin Disraeli; two military men, in the shapes of Sir Charles Napier and Charles Gordon; the architect Augustus Pugin and the legal authority Dicey; the great cricketer W. G. Grace and the administrator William Sleeman. Finally, Victoria herself and her consort Albert.

Each was patriotic but in a positive rather than an aggressive sense. Napier saw faults with England, especially in its relationship with Ireland but he also realised that the law was a force for good and would help people in India as much as it did at home. Gordon, like Napier, had a strong belief in the equality of all people. Each life was valuable to him and when he was victorious in battle he was generous. Similarly, he believed that spreading British civilisation, and specifically stifling the slave trade, was an intrinsic good in its own right. Victoria, as she presided over an age and a culture, embraced a vision of equality for all of her subjects and was in no doubt that her rule was essentially benign. Indeed, her treatment of her non-British servants maddened her Court but it was a crucial part of her understanding of her imperial role.

Disraeli also understood the importance of a collective vision. His political drive was to improve the condition of the people and to make two nations one. Palmerstons patriotism was the most muscular but the main point of his vision, encapsulated in his famous Civis Romanus sum speech, was that it included all British subjects. Sleeman is in some ways the most thoroughly conventional of the individuals collected in this book, for he was an arch-bureaucrat convinced that British administrative processes could use British law to counter and stop a great evil. Dicey saw with clarity how the law worked and how it related to the unique British constitutional settlement and his legal thinking developed a new orthodoxy. This remarkable man ensured that a true understanding of the Constitution is an absolute subject for romanticism which is of continuing benefit to the nation.

Each figure, whether it be Grace wielding a cricket bat or Gladstone with a moral vision in defence of the Christians in Bulgaria, had confidence in the positive nature of their home nation. The origins of this moral vision predate the age: the early nineteenth-century Prime Minister George Canning, although he died before Victoria came to the throne, was a strong influence on both Palmerston and Peel. Canning declared resoundingly, We avow ourselves to be partial to the COUNTRY in which we live notwithstanding the daily panegyrics we read and hear on the superior virtues and endowments of its rival and hostile neighbours. We are prejudiced in favour of her Establishments, civil and religious; though without claiming for either that ideal perfection, which philosophy today professes to discover in the more luminous systems that are arising on all sides of us. These words epitomise the wise confidence that the Victorians placed in their nation.

Next page