A Oneworld Paperback Original

This ebook edition published in North America, Great Britain and Australia by

Oneworld Publications, 2016

Copyright David Gange 2016

The moral right of David Gange to be identified as the Author

of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-828-3

eISBN 978-1-78074-829-0

Typeset by Silicon Chips

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street

London WC1B 3SR

England

Stay up to date with the latest books, special offers, and exclusive content from Oneworld with our monthly newsletter

Sign up on our website

www.oneworld-publications.com

Introducing the Victorians

The Condition of England, on which many pamphlets are now in the course of publication, and many thoughts unpublished are going on in every reflective head, is justly regarded as one of the most ominous, and withal one of the strangest, ever seen in this world.

Thomas Carlyle, Past & Present (1843)

New Queen, new age?

On 28 June 1838, almost exactly a year after the death of her uncle, King William IV, Queen Victoria was crowned in Westminster Abbey. William IVs coronation in 1831 had been the first to feature a procession by carriage through the streets of London. Victoria followed suit but took a far longer, almost circular, route. Londoners, as well as nearly half a million visitors to the capital, observed the royal parade in all its glory. Nobles and dignitaries from around the world were present to demonstrate their respect for the new Queen. Yet press reports often chose to focus not on aristocratic wealth or royal grandeur but on the dark and heaving masses who lined the route. These crowds were full of eager expectation but also carried a hint of threat in this politically unsettled era. Would the eighteen-year-old Queen be overwhelmed by the sight of these thronging masses? The Duchess of Sutherland was on hand to help her conceal her emotions and the processions first port of call, the Ordnance Office, was manned by Royal Artillery in case the vast masses that pressed on all sides, deepening and accumulating, should give in to the unruly instincts of the mob.

This parade was the high point of an otherwise inauspicious coronation. The ceremony itself was unrehearsed, disorganized, and mishandled (the modern, micromanaged event, seen at the coronation of Elizabeth II, was, despite its medieval trappings, invented only in 1902). The young Queen spent much of the five-hour service, during which she wore three dresses, eating sandwiches from the altar of a side chapel. The traditional coronation banquet was not even held, and the mood was dampened by news of anti-royal protests held in Northern English cities such as Manchester and Newcastle. This was a ceremony too ostentatious for radicals, who required that the will of the people, not the monarch, be placed at the centre of public life, but too unspectacular for Tories, who demanded pomp to demonstrate royal authority.

This was also among the most unlikely coronations in British history. The young Victoria had been fifth in line just a few years earlier, but would have slipped further from the throne if any of her fathers three brothers had fathered children who survived beyond infancy. Only a series of accidents a strange destiny had led to the events of 28 June. Many of Victorias subjects believed strongly in the power of destiny (or providence as Victorian religion styled it) to define personal and national fortunes, and by the time the Queens fate had taken its course she was not just monarch of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, Defender of the Faith, Princess of Hanover, and Duchess of Brunswick but also Queen of vast colonies and Empress of India. Britannia ruled an extraordinary number of waves.

As with most supposed destinies, there were substantial cracks in the impressive facade. Victorias reign was as troubled as her coronation. Her accession took place at a time when the nation she ruled was divided. The gulf in wealth and resources between rich and poor was large and constantly increasing, while conflict between European powers remained probable despite the fragile settlements that followed the Napoleonic Wars. Disagreement raged over the nature of state and society: in most circles, democracy remained a dirty word, while in some it was emerging as the rallying cry for a reformed politics, free from the elite domination and corruption of the old regime.

The young Queen, less conservative than her Tory uncle William IV, gave such hope to the champions of democracy that radical ballads were sung in her honour. In a parliamentary system where Whigs often favoured values that might loosely be termed liberal and Tories stood for conservative ideals, Victoria was a Whig monarch, with a Whig government. However, in 1838, it was not clear what direction the following decades would take. Would the deepening and accumulating masses rise, as they had in France fifty years before, to demand a more substantial redrawing of politics than had been provided by the meek and mild Reform Act of 1832? Or would the powerful Tory contingent in Parliament embark on its golden age, strengthened by the controlled reform of the early 1830s, with its claim to represent Britain (symbolically rather than democratically) more credible than ever before?

The spell cast by the word Victorian

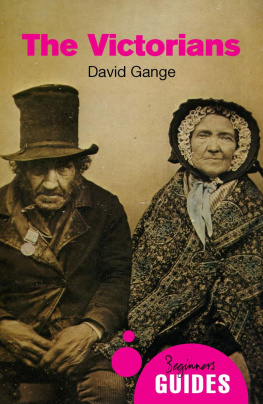

This Queens name gives us a term that conjures many vivid images: lace and crinoline, top hats and petticoats, steam trains and horse-drawn cabs. It suggests child labour in factories and mines, corporal and capital punishment, street crime, acceptance (even approval) of domestic abuse, and a stern religion that damned all but a few to hell. It suggests the mundane violence of the strap-wielding father and the infamous cruelty of Jack the Ripper. But maybe vivid is the wrong word for these images since they reach us in shades of sepia and grey that befit the nostalgic and repressed Victorians of our imagination. This is the first era for which we possess a photographic record, and the peculiarities of the Victorians efforts to negotiate their strange new technology informs our view of them. Morbidly, they photographed their dead. Earnestly, they did not dare to smile when photographed. Rigidly, they only very rarely betray small informalities in front of the lens. Lengthy exposure times necessitated the stiff formality that we too readily assume the Victorians to have embodied in everyday life.

In photographs, we see everything of these people except the colours; everything except the unguarded expressions that convey character; everything but what went on in their heads. These photographs impress a caricature on our memories: an era that is close to us in time, yet in ethos and atmosphere is everything we are not. The Edwardians invented this image of the Victorians as their opposites, the other against which they defined themselves. We have allowed this habit to persist. Where we nurture children, the Victorians exploited them; where we pursue equality in class and gender, the Victorians protected institutions that sustained inequality; where we are spontaneous, liberated, and funny, the Victorians were earnest, uptight, and humourless.