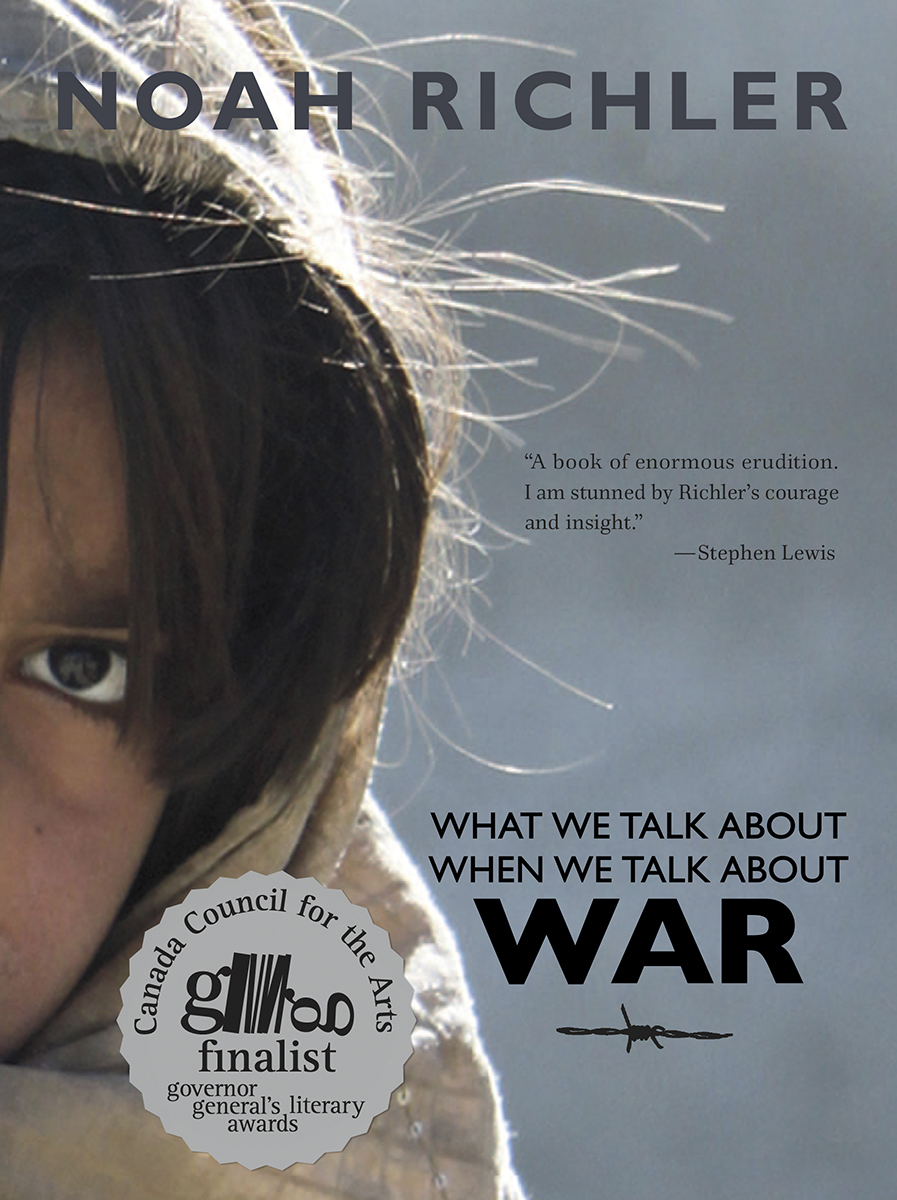

This is a book of enormous erudition. I am stunned by Richlers courage and insight. He dares to take on the pathology orchestrated by the military apologists in our political, academic and media establishment; debunking it, dismembering it, eviscerating it. Rarely does someone of letters take on such a subject and convey the argument with such force and clarity. Theres no question that the apologists will have exquisite apoplexy, but surely thats the ultimate tribute. The rest of us will exult in his embrace of the values of peace and decency, in a Canada that once was and might yet be again.

Stephen Lewis, former Canadian Ambassador to the UN

Well-written and passionate, this is a fine polemic about important issues. You dont have to agree with everything Noah Richler says I dont but you must take him seriously.

Margaret MacMillan, author of Paris 1919

Noah Richler has written an important book of great clarity, insight and courage. Like George Grants classic Lament for a Nation , it ranges from politics to philosophy, from literature to the mass media, in support of an intelligent, passionate and highly articulate argument. What We Talk About When We Talk About War deserves to be read and discussed in every political office, classroom, book club and Legion hall in the country.

Ron Graham, author of The Last Act

Since May 2nd, 2011, Canadians have watched their country swerve from the middle lane to the far right. A country once proud of its role as a peace-making moderate is being reconstructed as a Canada defined by war, violence and death. The change is brutal and deeply divisive. Noah Richler has taken the trouble to tell us why Canadians should worry.

Desmond Morton, author of Who Speaks for Canada?

In a way that is utterly free of jingoism, What We Talk About When We Talk About War demonstrates that the rabid outpourings of the mid-war years in Afghanistan have been blown away in a gust of Arctic air. A tonic to the spirit, Richlers book explores the rootedness of Canadian values and connects them to the experience of life in an enormous and damn lucky country.

James Laxer, author of Tecumseh and Brock

Noah Richlers important book reminds us why it is essential that we question the motives of military missions bathed in slogans. What We Talk About When We Talk About War provides a thorough analysis of our countrys myths of combat and of peace and, separating rhetoric from truth, incisively exposes the key players bent on convincing us of the merits of a just war.

Amy Millan, singer, songwriter with Stars and Broken Social Scene

A timely and thought-provoking examination of how we, as a nation, have allowed our perception of ourselves to be changed from peacekeepers to warriors, how the real-life experiences of the monstrous brutality of World War I have become the nation-building myth of today, and how our preference for peace, order and good government has graduated to a willingness to die for the sake of a greater cause. Richler urges us not to ignore these major, unexamined changes in the Canadian narrative lest we are redefined into a people we have never wished to be.

Anna Porter, author of The Ghosts of Europe

The questions Noah Richlers What We Talk About When We Talk About War poses resonate deeply, and while I may not agree with some of his conclusions, Richler offers a compelling perspective and unearths a treasure chest of sources, references and incidents that will richly enhance anybodys quest to affirm what being Canadian really means. This book is a must-read for the aspiring military professional and every citizen who is concerned about perpetuating into the twenty-first century what we understand to be the Canadian Way.

Lt.-Col. (ret) Patrick B. Stogran, PPCLI, Veterans Ombudsman 2007-2010

Copyright 2012, 2014 by Noah Richler.

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright) . To contact Access Copyright, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call 1-800-893-5777.

Edited by Meg Taylor.

Cover image Do I Trust You (detail) by Cooper Cantrell, 2010.

Cover and page design by Julie Scriver.

eBook development: WildElement.ca

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada.

ISBN 9780864927019

Goose Lane Editions acknowledges the generous support of the Canada

Council for the Arts, the Government of Canada through the

Canada Book Fund (CBF), and the Government of New Brunswick

through the Department of Tourism, Heritage and Culture.

Goose Lane Editions

500 Beaverbrook Court, Suite 330

Fredericton, New Brunswick

CANADA E3B 5X4

www.gooselane.com

To Sarah

And what can we do here now, for at last we have no notion of what we might have come to be in America, alternative.

Dennis Lee, Civil Elegies

INTRODUCTION

Achilles Choice

The most persistent sound which reverberates through mans history is the beating of war drums.

Arthur Koestler, Janus: A Summing Up (1978)

War enters the unconscious early.

As children growing up in London, England, in the early 1960s about as far away in time from the end of the Second World War as Canada is today from Jean Chrtiens first turn as prime minister, the Oka Crisis and the introduction of the GST (which is to say not far at all) my sister Emma and I used to collect Action Men, the soldier dolls called G.I. Joes in North America. We had a lot of them, and made extra props, clothes and, in our backyard, whole installations of trenches and a No Mans Land from the broken ones on whose plastic limbs wed paint blood using red paint from our model airplane kits (Spitfires, Messerschmitts, Junkers, Lancasters and B-1 bombers). We had officers quarters, a mess tent and, behind the lines, a bar for time off. When Martha, our younger sister, was silly enough to have her Barbie doll wander into it well, the Action Men whod suffered at the front, who had lost their friends and drank too much because they didnt know how long they had to live, took turns assaulting her. So ended Barbies visits.

That bit of shame occurred several years before I came to understand my own sexuality or knew what an erection was, but, no matter, Id already learned plenty about war and heroism and what it was to be a man from a plethora of comic books, television shows and movies such as The Battle of Britain , Tobruk and The Great Escape down at the Kingston Kinema. On the way home from school, Id stop in at army surplus stores to buy Allied and German uniform crests and bits of old military junk that were far from useless to me. In one of these shops, I first saw the iconic poster of Steve McQueen on his motorbike making his great escape, the barbed wire over which hed vaulted safely behind him as he gazed with such serene bravado at the far horizon. I liked it so much I worried I was homosexual, which, of course, would not do in any of the army games we played in the schoolyard.

From the schoolyard we learn so much and a lot that needs the better part of a lifetime to be un learned. Graduating from the schoolyards various traps of male primitivism is the endgame of a good education in the schoolhouse proper, the point being to civilize young boys and girls (none in our school, damn it) and to teach what it means to be Barbie, victimized to be the German rather than the Action Man and, is the hope, why reason and not might is the best arbiter of what is just. The schoolyards simple animal indoctrination never really disappears from our consciousness but is suppressed through the civilizing process to be managed by the rules of school and family and, later, by laws. We are taught not to bully the fat boy or the kid who stammers or the one who wets his pants and to include these children in our games and rituals. We are taught to recognize the virtues each may have and, in so doing, that folk who appear different or lesser are as entitled as any other to the same privileges and the right not to be at school in fear. But these are hard lessons, the order that is taught a fragile edifice. Under stress, we revert to the natural order of the schoolyard, call it the jungle, easily, and we do so in the barbarous theatre of war most of all.