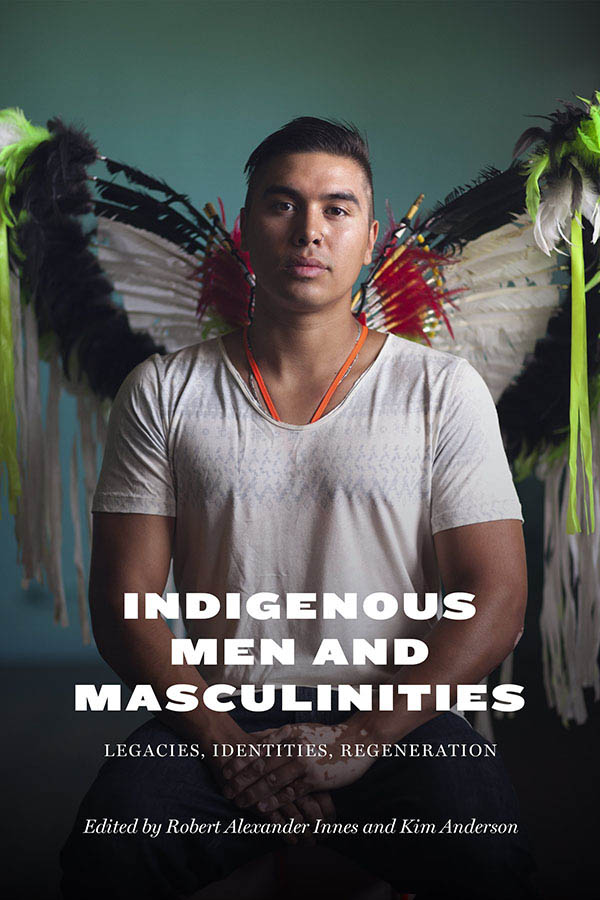

INDIGENOUS MEN

AND MASCULINITIES

Legacies, Identities, Regeneration

Edited by

Robert Alexander Innes and Kim Anderson

University of Manitoba Press

Winnipeg, Manitoba

Canada R3T 2M5

uofmpress.ca

The Authors 2015

Printed in Canada

Text printed on chlorine-free, 100% post-consumer recycled paper

19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database and retrieval system in Canada, without the prior written permission of the University of Manitoba Press, or, in the case of photocopying or any other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright (Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca, or call 1-800-893-5777.

Cover photo by Thosh Collins

Cover design: Marvin Harder

Interior design: Karen Armstrong Graphic Design

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Indigenous men and masculinities : legacies, identities, regeneration/ Kim Anderson, and Robert Alexander Innes, editors.

Includes bibliographical references.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-88755-790-3 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-88755-479-7 (pdf )

ISBN 978-0-88755-477-3 (epub)

1. Native menCanadaSocial conditions. 2. Native menCanada Psychology. 3. Native peoplesKinshipCanada. 4. MasculinitySocial aspectsCanada. I. Anderson, Kim, 1964, editor II. Innes, Robert Alexander, editor

E98.M44I53 2015 305.38897071 C2015-903456-6 C2015-903457-4

The University of Manitoba Press gratefully acknowledges the financial support for its publication program provided by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund, the Canada Council for the Arts, the Manitoba Department of Culture, Heritage, Tourism, the Manitoba Arts Council, and the Manitoba Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Contents

Robert Alexander Innes and Kim Anderson

Bob Antone

Scott L. Morgensen

Leah Sneider

Brendan Hokowhitu

Kimberly Minor

Erin Sutherland

Lisa Tatonetti

Niigaanwewidam James Sinclair

Phillip Borell

Robert Henry

Allison Pich

Lloyd L. Lee

Ty P. Kwika Tengan, with Thomas Kaauwai Kaulukukui, Jr. and William Kahalepuna Richards, Jr.

Sam McKegney, with Richard Van Camp, Warren Cariou, Gregory Scofield, and Daniel Heath Justice

Sasha Sky

Kim Anderson, John Swift, and Robert Alexander Innes

List of Tables

List of Illustrations

INDIGENOUS MEN

AND MASCULINITIES

INTRODUCTION

Whos Walking with Our Brothers?

Robert Alexander Innes and Kim Anderson

In June 2012, Mtis artist Christi Belcourt put out a call for moccasin tops, known as vamps, as part of a project to honour the missing and murdered Indigenous women in Canada. The organizers had hoped to receive 600 vamps, but instead received over 1,800. The vamps were put together to form an art installation called Walking With Our Sisters that will end up travelling across Canada to nearly thirty locations by 2020. This initiative follows the work of other activists; for example, the Native Womens Association of Canada (NWAC) first reported the issue of missing and murdered Indigenous women in their 2008 report Voices of Our Sisters In Spirit, and NWAC has undertaken a very successful awareness campaign through its annual Sisters in Spirit Vigils held in many communities across Canada. The Voices of Our Sisters In Spirit, Sisters In Spirit Vigils, and the Walking With Our Sisters installation have brought national attention to the Indigenous women who have gone missing or who have been murdered in Canada.

As these campaigns demonstrate, substantial attention has been focused on the struggles of Indigenous women, and rightfully so, considering their social and economic conditions. In comparison, however, there is a lack of theoretical and applied scholarly work about Indigenous men and masculinities. This reflects the fact that there is little activism or political will to address Indigenous mens issues, and as a result there are very few policies or social programs designed for Indigenous men, including those who are trans-identified, as well as women who identify with Indigenous masculinities. There is, however, an emerging field of Indigenous masculinities studies, and this allows those of us involved to investigate an area that has been largely ignored.

In many ways, the conditions of Indigenous men, though distinct, are similar to those of Indigenous women, but these conditions have not really been acknowledged beyond news reports of their criminal behaviour. Indigenous men also face the same sort of race and gender biases as do other men of colour, and this leads to a host of social issues for them and their communities. In Canada, for example, and in comparison to non-Indigenous Canadians, Indigenous men have shorter life spans, and are murdered at a higher rate. With the lack of political will and public awareness of Indigenous men and masculinities, we might well ask: Who is walking with our brothers?

Indigenous men and those who identify with Indigenous masculinities, as this book shows, are faced with distinct gender and racial biases that cause many to struggle. This book of essays explores and seeks to deepen our understanding of the ways in which Indigenous men and those who assert an Indigenous male identity perform their masculine identities, why and how they perform them, and the consequences to them and others because of their attachment to those identities. As the authors in this volume clearly show, the performance of Indigenous masculinities has been profoundly impacted by colonization and the imposition of a white supremacist heteronormative patriarchy that has left a lasting and negative legacy for Indigenous women, children, Elders, men, and their communities as a whole. At the same time, this book details the regeneration of positive masculinities currently taking place in many communities that will assist in the restoration of balanced and harmonious relationships.

One step toward achieving healthy Indigenous masculinities and communities includes reaching an understanding of how race and gender bias intersect to disadvantage Indigenous men, and how this disadvantaged position has had negative ramifications for Indigenous communities. In a January 2014 piece for Al Jazeera online, UCLA law professor Khaled Beydoun provides a discussion of the intersection of race and gender bias experienced by men of colour in the United States that is applicable to Indigenous men in Canada and their experiences. Beydoun links the negative treatment heaped on men of colour not only to racial discrimination but also to gendered discrimination. However, since these acts of discrimination are against men (of colour), most people fail to see them being tied to gender. As Beydoun points out:

Gender discrimination is overwhelmingly discussed and examined within a vacuum, divorced from the racial realities that broaden its practical relevance. As a result, gender discriminationin both lay and academic circlesis largely understood as animus endured by women, and most frequently, white women.

Discrimination endured by men of colour is framed within liberal circles as racial or ethnic animus, but seldomif everexamined from a conjoined gender lens. The distinct tropes associated with black and brown masculinity, however, attract a distinct brand of