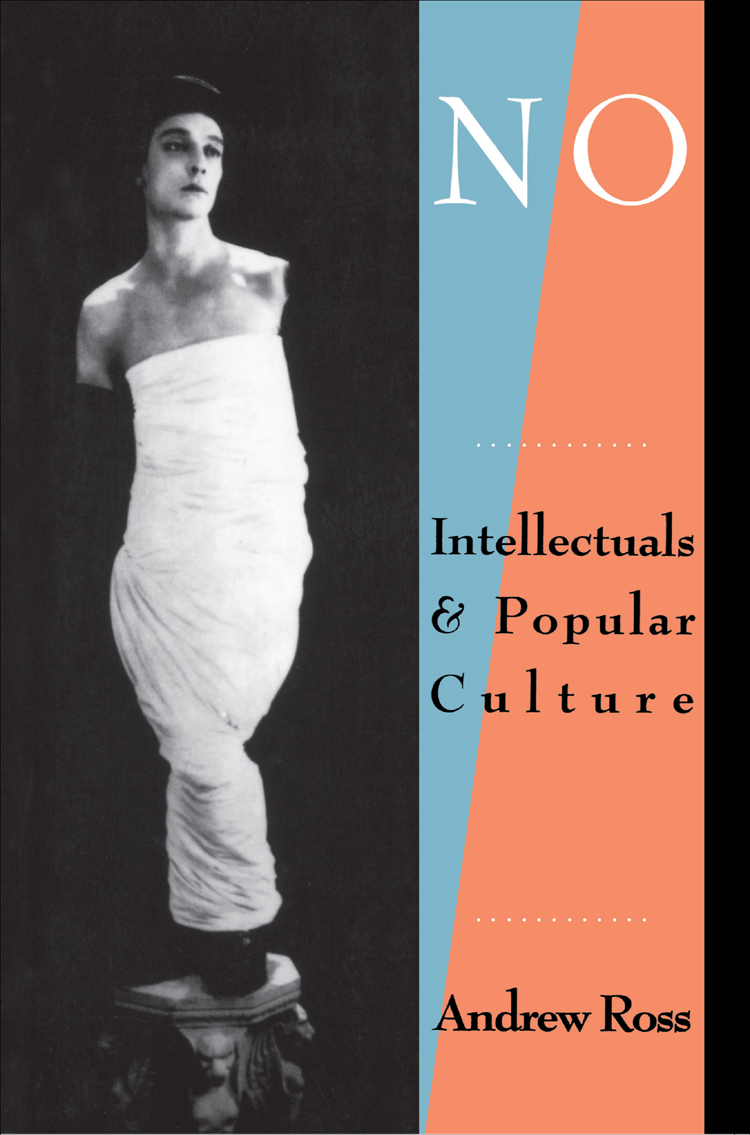

Ross - No respect: intellectuals et popular culture

Here you can read online Ross - No respect: intellectuals et popular culture full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: New York;USA, year: 1989;2014, publisher: Taylor and Francis;Routledge, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

No respect: intellectuals et popular culture: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "No respect: intellectuals et popular culture" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ross: author's other books

Who wrote No respect: intellectuals et popular culture? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

No respect: intellectuals et popular culture — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "No respect: intellectuals et popular culture" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

i NO

RESPECT ii

RESPECT

............

Intellectuals & Popular Culture

............

Andrew Ross

iv First published in 1989 by Routledge

Published 2014 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY, 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1989 by Routledge, Chapman and Hall, Inc.

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-90037-9 (pbk)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ross, Andrew, 1956

No respect: intellectuals and popular culture/Andrew Ross.

p. cm.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

ISBN 0415900360; ISBN 0415900379 (pbk.)

1. United StatesCivilization1945 2. United StatesPopular culture. 3. United StatesIntellectual life20th century. 4. IntellectualsUnited StatesHistory20th century. I. Title.

E169.12.R675 1989 | 895880 |

British Library Cataloging Data also available

v For Jean, my mother, and in memory of Ben, my father vi

viii

Writing No Respect was not a lonely business. Help was everywhere at handfrom guardian angels, family, friends, colleagues, editors, correspondents, and a whole assortment of imaginary acquaintances and superegos.

Some of the books materials were first presented as talks, and Im grateful to those who invited me to lecture and to those in the audience who responded at the following universities: SUNY Buffalo, Cornell, Yale, York, Northwestern, Rochester, SUNY Stonybrook, Columbia and UMass Amherst.

First drafts of the whole book were treated to invaluable readings and critiques from Larry Grossberg, Paul Smith, Harvey Teres, and Constance Penley. In addition, individual chapters benefited no end from the comments of Paula Treichler, Linda Williams, David Bromwich, Sharon Willis, Alan Sinfield, Jan Radway, and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. Thanks are also due to many others for help, advice, comments, and enlightenment: Steve Fagin, Dana Polan, Bill Warner, Anne Norton, Stanley Aronowitz, Lauren Berlant, Michael Rogin, Cary Nelson, Deborah Esch, Ian Balfour, Michael Cadden, Jonathan Arac, Alex Doty, Mary Caputi, Bruce Robbins, David Lloyd, Jules Law, Stuart Hall, Anne McClintock, Elaine Showalter, Mark Seltzer, Shirley Samuels, Danny Goldberg, Anders Stephanson, and all those on the Social Text collective.

A special note of gratitude to Eva and all the gang at Rush Rhees Library in Rochester for all the fabulous help they provided. My thanks, also, to students in my seminars at Princeton and Rochester from 198688 who were accomplices in the critique of tasteespecially to Elana Sigall, almost a collaborator.

Earlier and shorter versions of some of the chapters were originally published in Cultural Studies, Cultural Critique and The Yale Journal of Criticism. Thanks to the editors and to Yale University Press for permission to reprint, and also, for their encouragement and understanding, to my editor, Bill Germano, and copy-editor, Diane Gibbons, at Routledge.

The credits close with Constance, who, I think, likes music a lot more than she lets on. x

In a solo stage appearance, Bill Cosby tells a story about how he and his wife, because they were intellectuals, decided that she ought to have their child by way of natural childbirth. Nothing is more natural than giving birth; according to the movies, all you need is hot water, and plenty of it! On the other hand, intellectuals, he points out, are those people who go off to study things which other people do naturally, and so it seemed appropriate to them to attend exercise classes together, as they were advised to do, to prepare for the birth. In these classes, she practiced breathing, and he coached her, macho-style (both had university degrees in child psychology, but he had also majored in physical education). Come the big day, their nerve fails them, their newly acquired skills of breathing and coaching are found wanting, and, in the heat of the moment, more orthodox medical procedures are called for. The obstetrician who is attending, rather than directing the childbirth, is seen as a passive incompetent. Unlike Cosby, the enthusiastic, agitating coach, this doctor sits and watches, Johnny Bench-like, while Cosbys wife, at the first peak of pain, dramatically renounces the ideology of the drugfree delivery by demanding her fair share of morphine. The rest of this very funny sketch describes the subsequent trials and tribulations of Cosbys paternity, augmented by comparisons with his fathers competence at dealing with this role. Paternity, of course, turns out to be an endless condition of agonizing, about which Cosby, credentialed as a child psychologist and valorized as TVs most affable patriarch, is more than qualified to speak.

Where does this story come from? Perhaps it reflects a visible anxiety about the reproduction of a particular social class, that of the first-generation professionals to which Cosby and his wife belong. Too young and amorphous to have solidified its own interests, this social grouping still hangs on to its external, non-professional allegiances, especially those of its parents, and is unsure about the autonomy and power of its new social standing. Of course, this anxiety about social reproduction does not necessarily extend to other classes, and Cosbys caustic but nonetheless revealing proof of this is his example of ladies picking rice in the deprived countries of the world, who give birth in the fields to babies that immediately set to work at picking the rice themselves.

So too, his story betrays a suggestive anxiety about professionalism itselfif acquired skills and accredited knowledge are often seen to be worthless in the face of natural life, then the authority and privileges that come with them might also be unwarranted. This is an anxiety that speaks to a general ambivalence about, if not distrust of, the authoritative role of experts in peoples lives. Behind the perception that intellectuals acquire skills that are often superfluous lies an increasingly visible history of the expropriation, on the part of professionals, of the skilled amateur labor of working people. In the case of childbirth, for example, this history records the development of obstetric techniques which served to suppress the skills of midwives and to take childbirth out of homes and communities by placing it under institutional supervision. Consequently, childbirth became defined as a scientific, and not a natural event. Generally speaking, it is a history that explains how the cultural authority of professionals arose from establishing responsibility for what other people do naturally, and thus depriving them of control over their daily environments.

That Cosbys story is able to invoke these anxieties, fears, and resentments reflects in part the widespread expression of disrespect for authority which grew out of challenges to institutionalized expertise in the sixties and seventies. Such challenges to the perceived privileges and alienating practices of doctors, lawyers, professors, administrators, politicians, etc., resulted in the local popularity, for instance, of alternative health care for women and other self-help attempts to reappropriate skills and powers from the experts. Like many comedians, Cosby gets a lot of his laughs out of playing upon the distrust of experts (doctors and dentists and others), but it is important to recognize that there are always ideological limits to this disrespect, and it is here that the many facets of the Cosby character come into play as a way of managing this disrespect; he is a hip, successful, middle-class black male, a professional comedian, a celebrity who is responsible to certain liberal causes, and an actor whose earliest TV roles always emphasized an educated, professional training and who currently plays the role of a patriarch and doctor in the astonishingly popular

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «No respect: intellectuals et popular culture»

Look at similar books to No respect: intellectuals et popular culture. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book No respect: intellectuals et popular culture and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.