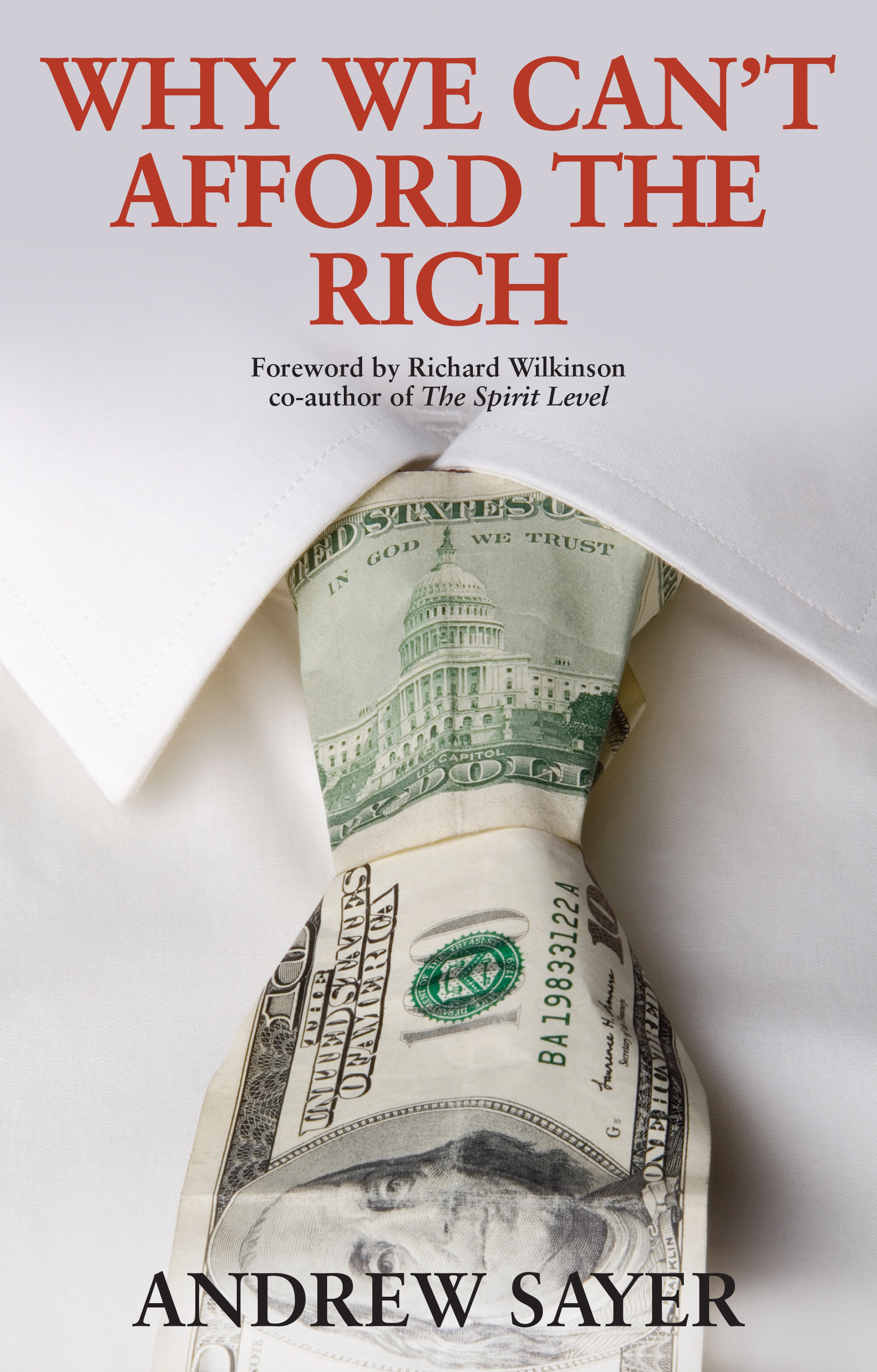

WHY WE CANT AFFORD

THE RICH

Andrew Sayer

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Policy Press University of Bristol 1-9 Old Park Hill Bristol BS2 8BB UK Tel +44 (0)117 954 5940 e-mail

North American office: Policy Press c/o The University of Chicago Press 1427 East 60th Street Chicago, IL 60637, USA t: +1 773 702 7700 f: +1 773-702-9756 e:

The Policy Press 2015

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN 9781447320906 ePub

ISBN 9781447320913 Kindle

The right of Andrew Sayer to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the 1988 Copyright, Designs and Patents Act.

All rights reserved: no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of Policy Press.

The statements and opinions contained within this publication are solely those of the author and not of the University of Bristol or Policy Press. The University of Bristol and Policy Press disclaim responsibility for any injury to persons or property resulting from any material published in this publication.

Policy Press works to counter discrimination on grounds of gender, race, disability, age and sexuality.

Cover design by www.thecoverfactory.co.uk

Front cover image: www.istock.com

Contents

List of figures

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to:

all the investigative journalists, academics, bloggers, activists and campaigners who have exposed the processes that support the rule of the rich and the denial of climate change;

the Economic and Social Research Council for a Fellowship in 200405 which allowed me to get started on moral economy, as did a sabbatical from Lancaster University;

Colin Gordon, Emmanuel Saez, Mike Norton, John Hills and Tom Palley for permission to use their data or graphs; to New Society Publishers for .

Bob Jessop for regularly alerting me to sources of data and alternative news and, with the usual disclaimers, for comments on much of the text for which thanks also to Dean Curran, Norman Fairclough, Dimitri Mader, Kevin McSherry, David Tyfield, Dick Walker and John Urry;

Danny Dorling and an anonymous reviewer for invaluable suggestions;

John Allen, John Baker, Gideon Calder, Aditya Chakrabortty, John Christensen, Mick Dunford, Michael Edwards, Norman and Isabela Fairclough, Tony Fielding, Neil Foxlee, Russell Keat, Kathleen Lynch, Kevin Morgan, Betsy Olson, John ONeill, Diane Perrons, Kate Pickett, Karen Rowlingson, Balihar Sanghera, Clive Spash, Richard Wilkinson, Ruth Wodak and the Language, Ideology and Politics group at Lancaster, Linda Woodhead, Erik Olin Wright and many others for discussions, advice, data and encouragement;

all those other friends who kept asking when is it coming out? while, in the nicest possible way, distracting me from finishing it: Ann McChesney, Pat Batteson, Dinah Brown, Eric and Cecilia Clark, Isabela Fairclough, Steve and Anne Fleetwood, Anne-Marie Fortier, Bridget Graham and Tom Fairclough, Costis Hadjimichalis and Dina Vaiou, Frank Hansen and Helle Fischer, Iain Hunter and Sue Halsam, Ruth Joyce, Richard Light, Grazyna Monvid, Celia Roberts, Georg Schnfeld , Judy Sebba and Brian Parkinson, Eeva Sointu, Sue Taylor, Liz Thomas, Jill Yeung and Karin Zotzmann;

my other colleagues at Lancaster for friendly collegiality, and Karen Gammon, Jules Knight, Kate Mitchell, Cathlin Prill and Rachel Verrall for good-humoured and excellent administrative support in the department, despite understaffing;

Alison Shaw, Laura Vickers and the Policy Press team for encouragement, advice and support;

my daughter Lizzie, especially, as always.

I will be giving all royalties from this book to a selection of charities and organisations pursuing equality and economic justice.

Foreword

Andrew Sayer has written a very good book which does much more than its title suggests. As well as explaining why we cant afford the rich, it also explains why we go on doing so. The ideology that the rich shower on us is meant to justify their privilege, but it turns the truth completely inside out. When inequality reaches the insane levels it has done, the rich depend on hoodwinking us all into thinking that they are the source of jobs, prosperity and everything we value. But, to paraphrase George Monbiot, once we stop believing this, either governments have to tackle inequality or revolutions arise. So Sayers piece-by-piece unpicking of the economic justifications of the rich is an important political act.

Although this book has a light touch that masks the impressive scholarship which has gone into it, and is free of jargon and sometimes funny, to say it is a good read would belie its seriousness of purpose. Above all, Sayer is concerned to help our societies surmount what he rightly calls a diabolical double crisis at once economic and environmental. But too often reading books or articles on the threats the world faces becomes little more than a form of consumerism. We read them to feel well informed hopefully better informed than others. And it is easy to feel that the more threatening the problem under discussion, the more exhilarating it is as the plot of a whodunnit. Being well informed adds to our cultural capital and gives us more to say, but let us make sure this book also makes us part of the solution.

On the interface between the environment and inequality, Sayer quotes Pacala, saying that 7 per cent of the worlds population is responsible for 50 per cent of all greenhouse gas emissions. But even if we in the rich world give up flying, do without a car and eat little or no meat, we would probably reduce our total (direct and indirect) carbon emissions by no more than a third only a modest contribution to the 80 or 90 per cent we need to achieve.

Fortunately, well-being and high carbon emissions are not inseparable. Countries achieve high levels of happiness and life expectancy at a fraction of the carbon emissions per head of population produced by many of the richest countries, including Britain and the USA. The truth is that the rich developed societies are very inefficient producers of well-being particularly those with bigger income differences between rich and poor. According to WHO figures, over 20 per cent of the populations of the more unequal rich countries are likely to suffer forms of mental illness such as depression, anxiety disorders, drug or alcohol addiction each year. Rates may be three times as high as in the most equal countries. At the same time, measures of the strength of community life and whether people feel they can trust others also show that more equal societies do very much better. As discussed in The Spirit Level (Penguin, 2010), tackling inequality is an important step towards achieving sustainability and high levels of well-being.

As the populations of the developed world have gained unprecedented standards of comfort and material prosperity, further increases in those standards make less and less difference to well-being. But what has become critical to well-being is the social environment and the quality of social relations. There is abundant research showing that social life and relationships are essential to both health and happiness. However, very large material inequalities mean that status becomes more important and social life is increasingly impoverished by status competition and status insecurities. Social anxieties and our worries about how we are seen and judged are exacerbated. The result is that people start to feel that social life is more of an ordeal than a pleasure and gradually withdraw from social life as the data show.