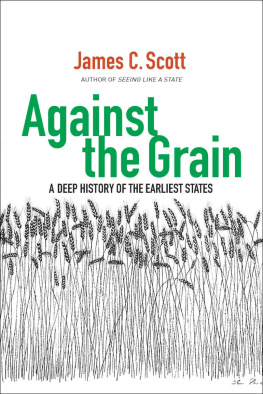

Against the Grain

Against the Grain

A Deep History of the Earliest States

JAMES C. SCOTT

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Amasa Stone Mather of the Class of 1907, Yale College.

Copyright 2017 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Janson and Monotype Van Dijck types by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016960155

ISBN 978-0-300-18291-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For my grandkids headed deeper into the Anthropocene

Lillian Louise

Graeme Orwell

Anya Juliet

Ezra David

Winifred Daisy

Claude Lvi-Strauss wrote thus:

Writing appears to be necessary for the centralized, stratified state to reproduce itself.... Writing is a strange thing.... The one phenomenon which has invariably accompanied it is the formation of cities and empires: the integration into a political system, that is to say, of a considerable number of individuals... into a hierarchy of castes and classes.... It seems to favor rather the exploitation than the enlightenment of mankind.

Contents

Preface

What you will find here is a trespassers reconnaissance report. Let me explain. I was asked to give two Tanner Lectures at Harvard in 2011. The request was flattering, but having just finished an arduous book, I was enjoying a welcome spell of free reading with no particular aim in mind. What could I possibly do in four months that might be interesting? Casting about for a manageable theme, I thought about the two opening lectures I had been in the habit of giving to a graduate course on agrarian societies for the past two decades. They covered the history of domestications and the agrarian structure of the earliest states. Although they had gradually evolved, I was aware that they were woefully out of date. Perhaps, I reasoned, I could hurl myself at the more recent work on domestication and the earliest states and at least write two lectures that would reflect newer scholarship and be more worthy of my discerning students.

Was I ever in for a surprise! The preparation for the lecture upset a great deal of what I thought I knew and exposed me to a host of new debates and findings that I realized I would have to put under my belt to do justice to the topic. The actual lectures, therefore, served more to register my astonishment at the amount of received wisdom that had to be thoroughly reexamined than to attempt that reexamination itself. Homi Bhabha, my host, selected three astute commentatorsArthur Kleinman, Partha Chatterjee, and Veena Daswho, in a seminar following the lectures, convinced me that my arguments were not remotely ready for prime time. Only five years later did I emerge with a draft that I thought was well founded and provocative.

This book thus reflects my effort to dig deeper. It is still very much the work of an amateur. Though I am a card-carrying political scientist and an anthropologist and environmentalist by courtesy, this endeavor has required working at the junction of prehistory, archaeology, ancient history, and anthropology. Not having any particular expertise in any of these fields, I can justly be accused of hubris. My excusewhich may not amount to a justificationfor trespassing is threefold. First, there is the advantage of the navet I bring to the enterprise! Unlike a specialist immersed in the closely argued debates in their fields, I began with most of the same unexamined assumptions about the domestication of plants and animals, of sedentism, of early population centers, and of the first states that those of us who have not been paying much attention to new knowledge of the past two decades or so are apt to have taken for granted. In this respect, my ignorance and subsequent wide-eyed surprise at how much of what I thought I knew was wrong might be an advantage in writing for an audience that starts out with the same misconceptions. Second, I have made a conscientious effort, as a consumer, to understand the recent knowledge and debates in biology, epidemiology, archaeology, ancient history, demography, and environmental history that bear on these issues. And finally, I bring a background of two decades trying to understand the logic of modern state power (Seeing Like a State) as well as the practices of nonstate peoples, especially in Southeast Asia, who have, until recently, evaded absorption by states (The Art of Not Being Governed).

This is, therefore, a self-consciously derivative project. It creates no new knowledge of its own but aims, at its most ambitious, to connect the dots of existing knowledge in ways that may be illuminating or suggestive. The astonishing advances in our understanding over the past decades have served to radically revise or totally reverse what we thought we knew about the first civilizations in the Mesopotamian alluvium and elsewhere. We thought (most of us anyway) that the domestication of plants and animals led directly to sedentism and fixed-field agriculture. It turns out that sedentism long preceded evidence of plant and animal domestication and that both sedentism and domestication were in place at least four millennia before anything like agricultural villages appeared. Sedentism and the first appearance of towns were typically seen to be the effect of irrigation and of states. It turns out that both are, instead, usually the product of wetland abundance. We thought that sedentism and cultivation led directly to state formation, yet states pop up only long after fixed-field agriculture appears. Agriculture, it was assumed, was a great step forward in human well-being, nutrition, and leisure. Something like the opposite was initially the case. The state and early civilizations were often seen as attractive magnets, drawing people in by virtue of their luxury, culture, and opportunities. In fact, the early states had to capture and hold much of their population by forms of bondage and were plagued by the epidemics of crowding. The early states were fragile and liable to collapse, but the ensuing dark ages may often have marked an actual improvement in human welfare. Finally, there is a strong case to be made that life outside the statelife as a barbarianmay often have been materially easier, freer, and healthier than life at least for nonelites inside civilization.

I am under no illusion that what I have written here will be the last word on domestication, on early state formation, or on the relation between early states and the people of their hinterlands. My goal is twofold: first, the more modest one of condensing the best knowledge we have of these matters and then suggesting what it implies for state formation and for both the human and ecological consequences of the state form. By itself, this is a tall order and I have tried to emulate the standard set for this genre by the likes of Charles Mann (1491) and Elizabeth Kolbert (

Next page