PREVENTIVE

WAR

AND

AMERICAN

DEMOCRACY

PREVENTIVE

WAR

AND

AMERICAN

DEMOCRACY

SCOTT A. SILVERSTONE

Routledge

Taylor & Francis Group

711 Third Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Routledge

Taylor & Francis Group

2 Park Square

Milton Park, Abingdon

Oxon OX14 4RN

2007 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business

International Standard Book Number-10: 0-415-95230-1 (Softcover) 0-415-95229-8 (Hardcover)

International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-415-95230-9 (Softcover) 978-0-415-95229-3 (Hardcover)

No part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers.

Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Silverstone, Scott A.

Preventive war and American democracy / Scott A. Silverstone.

p. cm.

ISBN 0-415-95229-8 (hardcover) -- ISBN 0-415-95230-1 (softcover)

1. United States--Foreign relations--1945-1989. 2. United States--Foreign relations--1989- 3. Preemptive attack (Military science)--Case studies. 4. United States--Foreign relations--Case studies. 5. Preemptive attack (Military science)--Government policy--United States. 6. United States--Foreign relations--Philosophy. 7. Democracy--United States. I. Title.

E744.S555 2006

327.117--dc22

2006023832

Visit the Taylor & Francis Web site at

http://www.taylorandfrancis.com

and the Routledge Web site at

http://www.routledge-ny.com

Contents

Preface

In the late 1940s and early 1950s the United States was on the threshold of the most dangerous threat ever faced in its history. In August 1949 the USSR broke Americas atomic monopoly; American leaders knew that in the coming years the Soviets would have a long-range bomber force and an atomic arsenal large enough to deliver a devastating attack against the American homeland. This was a threat ripe for the strategic logic of preventive war. Some argued that America must launch a preventive attack while it still had an atomic advantage, to avoid the nightmare of an atomic Pearl Harbor that could cripple the United States. Despite the great fear of growing Soviet power shared widely across American society, preventive war was decisively rejected as a possible solution. In 1946, Arnold Wolfers, who McGeorge Bundy called the dean of American students of international relations, explained this in simple terms: preventive war is abhorrent to the American people, too immoral for serious consideration.

This was not an idiosyncratic view. For statesmen, scholars, opinion leaders and average citizens of this period, a war launched in the absence of a truly imminent threat or in response to anothers attack was raw aggression. It was seen as contrary to the American character and its traditions of foreign policy, a violation of deeply held normative beliefs about the conditions that justify the use of military force. Fifty years later, in seeming defiance of these beliefs, the United States launched the first preventive war in its history against Iraq.

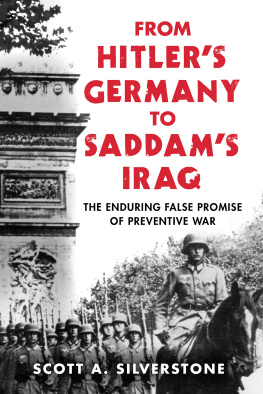

This book explores the idea of preventive war in American strategic decision making, from the early Cold War strategic problems created by the growth of Soviet and Chinese power, to the post-Cold War fears of a nuclear-armed North Korea, Iraq, and Iran. It examines how Americans have wrestled with the normative implications of preventive war in the face of a shifting threat environment, and how beliefs about preventive war actually shaped American policy. An important goal is to explain why a normative belief that had a decisive restraining effect on American power at mid-century had become impotent by the twentieth centurys end. In the process this book avoids the sharp partisan and ideological tone of much of the discussion of preventive war generated by the 2003 invasion of Iraq. A glut of books and articles have weighed in on whether this preventive war was in fact just or unjust, internationally legal or illegal, smart or foolish militarily. Rare is the discussion that takes a purely empirical approach to this vitally important topic in American foreign policy. This book tackles that objective.

I would like to thank Joel Rosenthal, president of the Carnegie Council on Ethics and International Affairs, for his early support of this research. A fellowship with the Carnegie Council in 20032004 produced a burst of momentum behind this project that helped sustain my work until the books completion. Others have provided invaluable advice at various stages, and I thank them for their help: Nina Tannenwald, Meena Bose, Bruce Jentleson, Tony Lang, Christopher Layne, John Owen, Carolyn James, and Richard Rupp. This book is dedicated to my grandfather, Vernon E. Saunders (19212004), whose life spanned the events discussed within, and whose worldview reflected the best of the American character.

Scott A. Silverstone

West Point, NY

The Preventive War Temptation versus the Anti-Preventive War Norm

With his commencement address to West Point graduates in June 2002, President George W. Bush set in motion an extraordinary national and international debate over waging war with Iraq. While he never mentioned Iraq specifically, the new strategic vision he unveiled in this speech, a vision centered on initiating preemptive wars against unbalanced dictators seeking weapons of mass destruction, was clearly inspired by this more immediate policy problem. Through the summer and fall this issue came to dominate American politics as political leaders, opinion makers, and the general public wrestled with the implications of this initiative and the seemingly resolute march toward war by the Bush administration in the early months of 2003. Among the different arguments cited to justify war against Iraq, one theme was dominant with those who supported this controversial option: the United States could not tolerate the uncertain threat environment created by the mere possession of chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons by the Iraqi regime. Administration officials never claimed to have evidence that Iraq was actually preparing to use these types of weapons against the United States or its allies, or that Iraq would actually provide them to terrorists. It was simply the potential for an attack by Iraq or its surrogates with weapons of mass destruction that was at the core of the strategic logic driving the move toward war. This strategic logic, in turn, makes the Iraq case a classic example of preventive war.

Preventive war is a persistent theme in the history of international politics and in theoretical explanations of war. In fact, as Paul Schroeder contends, preventive war has been a normal, even common tool of statecraft. A preventive war would thus deny Iraq this particularly potent military capability to challenge the status quo while allowing the United States to avoid the nightmare scenario of facing a nuclear Iraq in a future armed conflict. Even after the invasion of Iraq and the destruction of the Saddam Hussein regime, this same preventive logic has led American leaders to treat nuclear proliferation to such rivals as Iran and North Korea as a top national security problem. With the Bush administrations so-called preemption doctrine, articulated most formally in the National Security Strategy (NSS) of 2002 and reaffirmed in the 2006 NSS, preventive war remains the ultimate anti-proliferation policy tool to stop the spread of weapons of mass destruction.

Next page