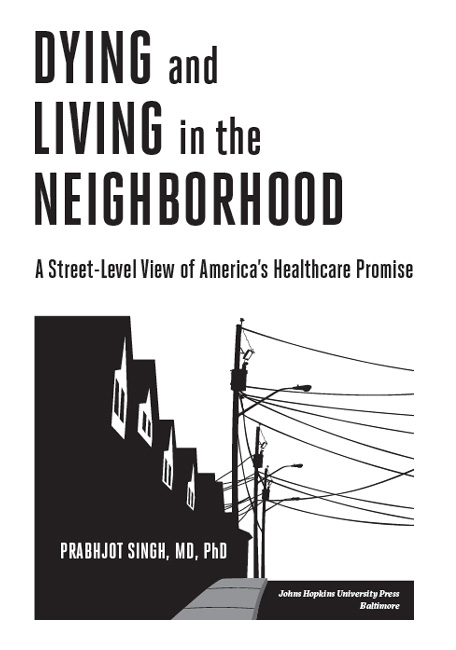

Dying and Living in the Neighborhood

Dying and Living in the Neighborhood

2016 Prabhjot Singh

All rights reserved. Published 2016

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Singh, Prabhjot, 1982, author.

Title: Dying and living in the neighborhood : a street-level view of Americas healthcare promise / Prabhjot Singh.

Description: Baltimore : Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015046696 | ISBN 9781421420448 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 1421420449 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781421420455 (electronic) | ISBN 1421420457 (electronic)

Subjects: MESH: Community Health Services | Preventive Health Services | Health Promotion | Health Policy | Chronic Diseaseprevention & control | Socioeconomic Factors | United States | Systems Architecting & Engineering |

Classification: LCC RA418 | NLM WA 546 AA1 | DDC 362.1dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015046696

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or .

Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

O physician, you are a competent physician, if you first diagnose the disease. Prescribe such a remedy, by which all sorts of illnesses may be cured.

Guru Nanak (d. 1469 CE)

Preface

If this man is a physician then it is self-evident that his science must include whatever is pertinent to his proclaimed purpose.

Rudolph Virchow, 1848

In 1982, the year I was born, the historian John Burnham wrote an article in Science entitled, American Medicines Golden Age: What Happened to It? This was the same year as the Chicago murders involving poisoned Tylenol capsules, which heightened a sense of danger in one of our most trusted industries, and the same year that Medicare began to fund hospice care. In the years since Burnhams article, scientific innovation like the Human Genome Project and healthcare management inventions like the health maintenance organization were both oversold to the American public as immediately advancing our ability to live healthier lives. I started medical and graduate school 20 years later, amidst rapidly rising healthcare costs, horror stories about hospital errors, a stagnant national biomedical research budget, and more than 40 million uninsured Americans. My colleagues and I inherited a narrative of healthcare in deep crisis, told by a profession hovering around its nadir.

In 2014, my last year of internal medicine residency, cardiologist Sandeep Jauhar published a widely read memoir entitled Doctored: The Disillusionment of an American Physician. He reported that only 6 percent of physicians had positive morale.which was increasingly perceived as an insider game of grant writing in an overly competitive funding environment. Scientists and physicians alike were (and are) upset that they could not simply do what they were trained to do. Instead, paperwork dominated the time of both, pushing the work of research and patient care to the margins.

This chastening has happened fairly quickly for an old and intense profession. My twenty-first-century training as a physician-scientist had a charming mid-twentieth-century flavor to it, lovingly shaped by people who were paragons of caring physicians and brilliant scientists. My colleagues and I spent years in small rooms, staring down the barrel of microscopes or moving precise aliquots of biological components with pipettes, or examining the skin and organs of patients and learning how to successfully draw blood. We communicated as peers within tight networks of researchers and from the bottom of strict hospital hierarchies.

If anything, our training took us back in time to the dawn of modern medical schools in 1910, when Abraham Flexner (backed by the Carnegie Foundations checkbook) took a strong stance in support of scientific medicine and against alternatives (e.g., naturopathic, homeopathic, osteopathic, chiropractic medicine). The first two years of medical school seemed to be designed to reinforce the supremacy of biomedicine over quackery, while the last two clinical years taught us how to apply the findings of biomedical and clinical research to the treatment of the patients in front of us. The most visible signs of a modern age were in the devices around us rather than in the methods we used to construct a differential diagnosis, devise a plan, and then communicate both to the patient in question.

By the time I started my graduate work at Rockefeller, under an extraordinarily kind scientist in the area of neural and genetic systems, I felt constrained by the kinds of questions that medical and scientific culture seemed reluctant to answer. Certainly, not all of my peers felt this way, and the brilliant and persistent among them found creative ways to move forward. But like thousands of others across the country, I looked abroad, to the poorest countries in the world and the growing field of global health, to find promise and purpose. I gravitated toward sub-Saharan Africa, where my parents were born and where I spent my early childhood before moving to Michigan and Pennsylvania, and finally, New York City.

Despite the limited resources, technology, and infrastructure, the opportunities I had alongside my experiences abroad were extraordinary. I joined the International Rescue Committee to learn about global population health in the context of refugee camps across the world. Because of my scientific background, they thought I could build an information system that would help them monitor the needs of thousands of refugees and anticipate the necessary supplies before they ran out. There was little in my medical training that prepared me for this task, except for the confidence to try. I built what they needed, which enabled them to demonstrate that a dynamic feedback system was as critically necessary as the needs and supplies it tracked. I predominantly spent time within sub-Saharan Africa, where I had the chance to seethrough a different, analytical lensthe places where my family had lived since moving from the Punjab at the turn of the twentieth century.

Throughout my travels, I thought about another nineteenth-century phenomenon: the work of Rudolph Virchow, German physician, anthropologist, politician, and scientist, whom I had learned about from my college history professor, Theodore Brown. Virchow is credited with bringing scientific thought to medicine, linking economic and political development with health improvement, and advancing the social dimensions of public health. Virchow provided me with a sharpened view of what medicine should be, one that implies a different culture of medicine than what prevails today. Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale. Medicine, as a social science, as the science of human beings, has the obligation to point out problems and to attempt their theoretical solution: the politician, the practical anthropologist, must find the means for their actual solution.

In a translation that Brown co-authored, I was surprised by Virchows views on how to address a devastating outbreak of typhus in a poor rural area of Prussia, where ethnic Poles lived under the thumb of empire. Without suggesting that scientific inquiry and clinical services were less important, he recognized that social, economic, and political reform came hand in hand with achieving better health. He saw that better health and socioeconomic development are intertwined and that healthcare at its best is a feedback loop that potentiates both:

Next page