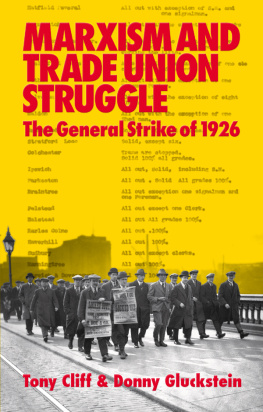

MARXISM AND TRADE UNION STRUGGLE

The General Strike of 1926

Tony Cliff and Donny Gluckstein

Acknowledgements

Many people have helped in the writing and preparation of this book. Thanks are due to Lynda Aitken, Peter Binns for help with the section on the Coventry Minority Movement, Alex Callinicos, Duncan Hallas, Alasdair Hatchet for assistance with the period 1919-20, Peter Marsden, Sheila McGregor, Penny Packham and Andy Strouthous.

Especial thanks are due to Chanie Rosenberg, who worked so hard in the TUC Library and Public Records Office.

Tony Cliff (1917-2000) was a founder and leading member of the Socialist Workers Party. His earlier publications included Rosa Luxemburg (1959), Russia: A Marxist Analysis (1963) (republished as State Capitalism in Russia [1974]), Incomes Policy, Legislation and Shop Stewards (1966) with Colin Barker, The Employers Offensive: Productivity Deals and How to Fight Them (1970), The Crisis: Social Contract or Socialism (1975), Lenin (four volumes 1975-9), Neither Washington nor Moscow (1982) and Class Struggle and Womens Liberation (1984).

Donny Gluckstein is a leading member of the Socialist Workers Party. He is the author of The Western Soviets: Workers Councils versus Parliament 1915-20 (1985).

MARXISM AND THE

TRADE UNION STRUGGLE

The General Strike of 1926

Tony Cliff & Donny Gluckstein

Marxism and Trade Union Struggle: The General Strike of 1926

Tony Cliff and Donny Gluckstein

First published April 1986

This edition published 2015

Bookmarks Publications

c/o 1 Bloomsbury Street, London WC1B 3QE

Copyright Bookmarks Publications

Printed by The Russell Press

Designed and typeset by Peter Robinson

Cover photograph: Striking engineers march across Blackfriars Bridge in London

ISBN print edition: 978 1 909026 86 5

Kindle: 978 1 909026 87 2

ePub: 978 1 909026 88 9

PDF: 978 1 909026 89 6

Contents

Preface

Marxism and Trade Union Struggle was originally written to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the General Strike. It is legitimate to ask, why re-publish now? The answer is that the events of 1926 epitomise perennial issues that confront Britains workers and socialists. The book was drafted in the shadow of the year-long great miners strike of 1984-5. Thirty years on, this new edition appears after the 30 November 2011 (N30) pensions strike, a day that mobilised the largest number of trade unionists since the General Strike.

Despite numerous attempts to write off the working class in favour of a nebulous multitude or some ill-defined precariat, all three episodes are graphic illustrations of the fundamental division that exists in capitalist society and the tremendous potential power of the working class. Equally, they are tragic examples that the potential is not automatically realised, as our class was defeated each time. Understanding the dynamics of what happens when mass strikes occur is an important question for anyone who wants to see radical change in society.

A comparison of 1926, 1984 and 2011 is revealing. Some trade disputes may take place in relative isolation from the general social, economic and political situation. But struggles on this scale cannot, and have to be seen in the round. In relation to the ruling class, there are great similarities between each. Driven by relentless competition and the unquenchable desire to accumulate, capitalists and their state were bent on attacking important sections of the working class. Tory governments were in power and each had a clear agenda: the defeat of one group of workers would help to intimidate all.

This organised class attack could only be successfully opposed by an organised class defence.

What was the situation on the workers side when battle was joined? At one level there were significant differences between the 1920s, 1980s and early 21st century.

The General Strike followed an almost unbroken sequence of upheavals which started with the syndicalist Great Unrest in 1910. Though briefly interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War, they were then given renewed energy by the shop stewards movement, the 1917 Russian Revolution and post-war mass struggles, such as the West of Scotland 40 hours strike which saw tanks deployed in Glasgow. The upswing was halted by a sudden economic crisis in the early 1920s, but the past was not forgotten and a new, vigorous Communist Party was established. When the mine owners (who had regained control of the pits at the end of the war) launched a vicious assault on pay and hours, the strength of all Britains trade unions was thrown into battle for nine glorious days of hope.

In 1984 the strike waves that had brought down the Tory government in 1974 were a thing of the past, the militancy of that period having been deliberately undermined by a Labour government. Unlike 1926, the mines were nationalised and the fight, in defence of pits and jobs, was in direct opposition to the hated government of Thatcher and its crusade against the so-called enemy within. However, in stark contrast to 1926, industrial action did not extend beyond the ranks of the National Union of Mineworkers to embrace other sections of workers, as opportunities for others to strike alongside the miners were scuppered by union officials. Therefore, the widespread sympathy the miners enjoyed remained limited to financial support. After a year of heroic resistance the Union was broken.

N30 was a strike of public sector workers who were opposing damaging changes to pension entitlement. Where the 1984-5 miners strike was limited in scale but extended in time, N30 was the opposite. It involved an enormous range of unions and diverse types of worker, but stopped after just one days action.

Politically, too, the situation was different on each occasion. Labour, the party backed by most workers, had progressed from youth, to maturity and then decrepit old age. In 1926, Labour had only recently adopted Clause 4 (for the social ownership of production) as part of its constitution and had briefly held office as a minority government; it appeared a relatively unknown quantity. By 1984, it had a long history of disappointing administrations behind it (only interrupted by that of 1945-51). By 2011, Clause 4 had been ditched, inner democracy had been destroyed and the left (Bennism), which had come close to capturing the Party not long before, had been rendered impotent. Labour now offered a slightly slower death by a thousand cuts than its Tory/Liberal rivals and their austerity plans.

Yet behind all of these disparities lie fundamental common features. Unlike all previous ruling classes, whose power arose from dominance over the means of production, working class strength grows when it unites as a collective force opposing exploitation. In Britain this is commonly expressed through membership of trade unions. 1926, 1984 and 2011 illustrated both this truth, and its constant corollarythat at the summit of trade unions lies a bureaucracy with different interests to those of the membership. When the union leaders called off the fight in mid-battle during 1926 and 2011 and studiously refused to offer solidarity in 1984, the result was disaster.

The distinctive feature of Marxism and Trade Union Struggle is that the behaviour of this bureaucratic caste is not explained by individual privilege (relatively higher pay and so on) or by the balance between left and right. While these play a role, the key enduring factor is the functional position of the bureaucracy between the capitalists and the workers. As the book puts it: union bureaucratsreformist, centrist or verbally revolutionaryhave a common group interest which means they must confine workers struggle within the system.

Next page