This book was the result of a collective effort, even if all of its faults belong to the author. Michael Burawoys feedback on the first part of the book, Peter Evans help with issues of development, and the comments of both over the years on political and social theory, as well as the EgyptTurkeyIran comparison, were central to the maturation of my arguments. Kevan Harris and Charles Kurzman read the entire manuscript and offered detailed reviews. Salwa Ismail weighed in with instructive criticism of the Egyptian parts of the book. I also benefited from their suggestions starting with the earlier stages of this comparative project.

Joel Beinin, Vicky Bonnell, Beshara Doumani, Marion Fourcade, Samuel Lucas, Raka Ray, Dylan Riley, Nezar AlSayyad, Berna Turam, Kim Voss, Susan Watkins, Margaret Weir and Tony Wood have all helped sharpen the comparative analysis as my study evolved. Especially helpful in fine-tuning the comparison were Asef Bayats, Ann Swidlers, Loc Wacquants, and Erik Wrights advice. I spent a semester at UCSD, where Richard Biernacki, John H. Evans, David Fitzgerald, Kwai Ng, Akos Rona-Tas, Gershon Shafir and Carlos Waisman contributed to my study of Iran, Egypt and Turkey. The audiences responses at two UCLA presentations (especially remarks by Perry Anderson, Robert Brenner, Rogers Brubaker, Hazem Kandil and Michael Mann) aided some of the conceptualization and comparison. As we worked on a comparative volume together, Cedric de Leons and Manali Desais interventions led to the further calibration of my EgyptTurkey comparison.

Finding my way in Egypts political and religious mazes wouldnt be possible without Momen el-Husseinys research assistance. Ghaleb Attrache provided last-minute assistance as I revised the manuscript. Funding from the Hellman Family Faculty Fund (University of California, Berkeley) facilitated some of the research in Egypt.

I wouldnt know how to interpret the maelstrom of change in Turkey if it were not for my daily debates with Aynur Sadet and zgur Sadet. My discussions of Turkish political economy with alar Keyder and Aye Bura were also immensely stimulating, and thanks to Zafer Yenal I could situate that economy within global capitalist dynamics.

If American neoconservatives and liberals disagreed on a range of burning issues, they united in their embrace of what they called the Turkish model. Around the turn of the millennium, the celebration of the Turkish model also brought together divided American and European elites: investment in the Turkish model could perhaps suture the wounds of a disintegrating global order. When US President George W. Bush gave a public speech at the end of the 2004 NATO summit in Istanbul, he stood on the grounds of a public university, further buttressing this rare concurrence. The TV cameras captured the magnificent Bosporus Bridge linking Europe and Asia and a beautiful Turkish mosque behind him. Thirty American and Turkish experts had worked on the choice of location and the specific setup. The bridge, as metaphor, informed his speech:

Your country, with 150 years of democratic and social reform, stands as a model to others, and as Europes bridge to the wider world. Your success is vital to a future of progress and peace in Europe and in the broader Middle East America believes that as a European power, Turkey belongs in the European Union. Your membership would also be a crucial advance in relations between the Muslim world and the West, because you are part of both. Including Turkey in the EU would prove that Europe is not the exclusive club of a single religion; it would expose the clash of civilizations as a passing myth of history Democratic societies should welcome, not fear, the participation of the faithful.

This inclusive message embraced Tayyip Erdoans pious regime, established in 2002. It took dozens of experts to combine these messages and images, but ordinary Turkish citizens had, in their own ways, already become virtuosos of such bricolage. When veiled women first started to drive SUVs in the 1990s, old-style secularists reacted furiously: how could the marvels of technology be polluted by signs of backwardness? By the 2000s, the practice had become so widespread that the reaction lost its meaning. Indeed, businesses capitalized on this articulation of dissimilar signs. In 2014, a booming conservative clothes company decorated the billboards of Istanbul with the image of two young women, fashionably clothed but veiled, driving a chic red convertible and looking around with coy smiles (rather than watching the road). Ultimately, even the anti-Islamists came to understand that pious people were wholeheartedly embracing many aspects of Western modernity, though they were still disturbed by the political implications of this convergence: Would the Islamists do away with democracy and personal freedoms once fully entrenched in power? Such doubts were sidelined in global public discourse, enchanted as it was by the bridge metaphor.

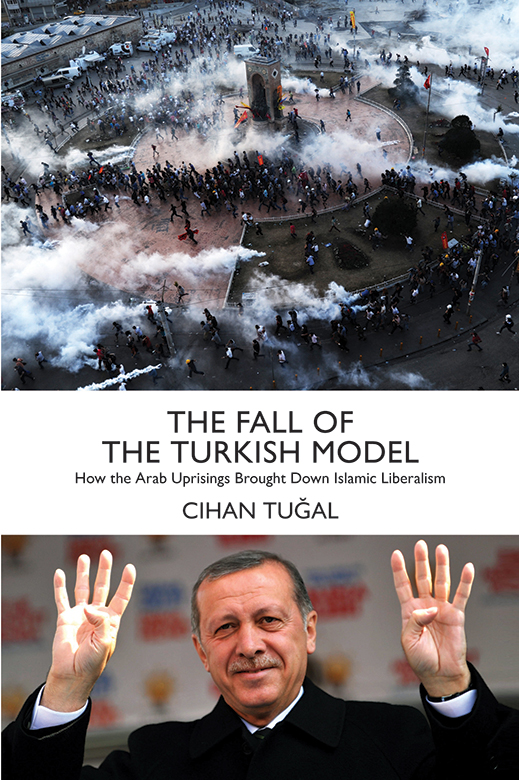

In the summer of 2013, however, new images started to populate the media: the tear gas used against peaceful Turkish protesters, gas masks that became everyday accessories and the prime ministers frequent posturing with the Rabia sign (a four-fingered salute). Erdoans government mercilessly repressed the protests in Istanbuls Gezi Park; the police even killed protestors elsewhere in June. Soon afterwards, Erdoan and his followers adopted the Rabia sign in solidarity with the uprising against the recent coup in Egypt, during which Islamists were massacred in Rabia Square (to which the four-fingered sign refers). While aggressively undermining liberties at home, Erdoan thus fashioned himself as supporting the slain Egyptian protestors, suggesting that his party defended civil liberties only for practising Muslims.

Although not a comprehensive account of that global scene, this book puts the liberalization of Islam within the context of Middle Eastern (and secondarily global) developments, to which revolts are central.

The last thirty-five years of the Middle East are full of revolutionary and pseudo-revolutionary dramas. Counter-revolts follow revolts. Inept leaders and organizations claim the pedestal of revolution only to carry out restoration. Their attempts at containment are clumsy and sooner or later give rise to new revolts.

The first major manoeuvre to absorb the Middle Eastern revolution came with the Islamic Republic of Iran, which erected a highly contradictory and explosive Islamic state (initially and temporarily) based on clerical-merchant containment of the urban revolts of 197879. In the decades that followed, the surrounding regimes scrambled for bits and pieces of Islam, democratization and populism to absorb the wave of revolution spreading from Iran all under diverse pressures from Washington and the IMF.