I was born and raised in Turkey and have studied Turkish politics for more than two decades. Since 1996, I have lived in the United States. Here and overseas, I frequently give lectures addressing audiences ranging from diplomats to citizens interested in global affairs. I also provide commentary for print media and networks, from the BBC to the New York Times.

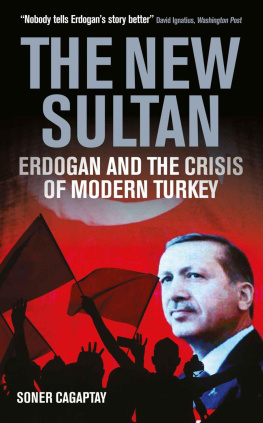

In 2017, I wrote the first-ever English-language biography of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, The New Sultan: Erdogan and the Crisis of Modern Turkey.

A good metaphor for Turkey is that of the onion, and this is one reason I enjoy studying it. Analytically speaking, the country is all layers but has virtually no core. Just as you think you have grasped Turkeys essence, a new layer emerges, forcing you to reconsider everything you previously thought you knew. Turkey defies simplistic generalizations and Manichean dualisms alike. Is Erdogan an autocratic leader? Yes. But will Turkeys democracy and populace wither under him? No. Turkeys democracy is resilient, its civil society robust, and its cohort of younger voters increasingly unhappy with the presidents style of governance.

Imagine the proverbial act of hammering a square peg into a round hole, and you can conceive of Erdogans conundrumhis challenge in trying to keep control of the forces that constitute todays Turkey. Since Turkey became a multiparty democracy in 1950, none of its leadersfrom Adnan Menderes in the 1950s to Turgut Ozal in the 1980shas succeeded in sustaining one-person rule in the country, regardless of their popularity.

Despite his lengthy tenure, I do not think Erdogan will break this trend. A country of 84 million citizens with an economy worth over $1 trillion in 2020 (measured according to current prices), along with a highly active civil society, large middle class, and tradition of robust democratic traditions, is too complex and diverse demographically, too large economically, and too complicated politically to simply become the province of one individual leader.

Like Turkey itself, Erdogan is a fascinating figure who often defies black-and-white characterizations. He controls Turkey, but as I explain below, he no longer truly leads it. He was born and raised in a poor Istanbul neighborhood but today lives in a palace with more than a thousand rooms in the Turkish capital, Ankara, as the countrys quasi-sultan. He fights against the elites for the interests of the common voter but himself embodies state, military, and religious power in Turkey. Last but not least, he is neither a dictator nor a democrat.

But one aspect of Erdogans career can be cast in black and white. He is among the inventors of nativist populist politics globally in the twenty-first century. Not unlike other nativist populist leaders, including former U.S. president Donald Trump, Erdogan has a base that loves him, but alsoand inverselyan opposition that simply loathes him and is eager to prosecute him should he fall from power.

And herein lies his key challenge: although Erdogans popularity is waning, he cannot afford to be voted out in elections. Erdogan is only about Erdogan. From now on, he will try to cover all his basessimultaneouslyto increase his chances for political survival. Every step he takes at homeunveiling a new democratic reform package in 2021 to restore his image in Washington and with global markets, even as he oppresses his opposition more harshly and creates deeper societal polarizationis meant to safeguard his career. The same can be said about his foreign policy bid to play Russian president Vladimir Putin and U.S. president Joe Bidenagain simultaneously.

Specifically, Erdogans twin goals are to boost the Turkish economy and his base. To this end, he will try to cherry-pick his way to success at the ballot box, again covering all his bases: demonizing the Kurdish nationalist opposition to rally his nationalist base, while legislating more de facto freedoms to appeal to markets; cracking down on vulnerable groups such as the LGBT community and women to appeal to conservative voters, while attempting to revive ties with the European Union and befriending President Biden.

With Biden in the White House, I am now also often asked by journalists about prospects for U.S.-Turkish relations in the Biden-Erdogan era. Enteronce againErdogans survival instincts, specifically his evolving relationship with Russian president Putin. Erdogan made a Faustian bargain with Russias president (explained in chapter 6) in August 2016 when the latter invited him to Saint Petersburg, following the failed Turkish coup attempt the previous month. During that visit, Putin offered Erdogan support and a power-sharing opportunity in Syria, while likely seeking, in return, Erdogans commitment to purchase the Russian-made S-400 missile-defense system, hence creating a permanent wedge in U.S.-Turkish ties.

Since that meeting, U.S.-Turkish relations have indeed deteriorated. What is more, the Erdogan-Putin relationship has developed new power-sharing branches, however tenuous they may be, stretching from Syria to the wars in Libya and the South Caucasus, where Ankara and Moscow back opposing sides. In other words, Erdogan is now too deeply enmeshed in his relationship with Putin, and Ankara is exposed to Moscows vicissitudes in key conflict areas both near and surrounding Turkey. Furtherin part because he knows Ankaras purchase of the S-400 system will undermine U.S.-Turkish tiesPutin will not allow Erdogan to renege on the deal. The latter understands he must play along or else face Putins wrath in Syria, Libya, and the South Caucasus. Putin can easily puncture Erdogans global strongman image, which the Turkish leader relies on domestically to boost his base. A further risk exists in the more than two million Syrian refugees who could arrive in Turkey should Putin greenlight an Assad regime assault on Idlib, the last rebel-held province in Syria. With anti-refugee sentiment rising in Turkey, even Erdogan would be unable to manage the economic burdens and political trends triggered by such a development.