Contents

Page List

Violence Studies

Felix Murchadha

General Editor

Vol. 1

This book is a volume in a Peter Lang monograph series.

Every volume is peer reviewed and meets

the highest quality standards for content and production.

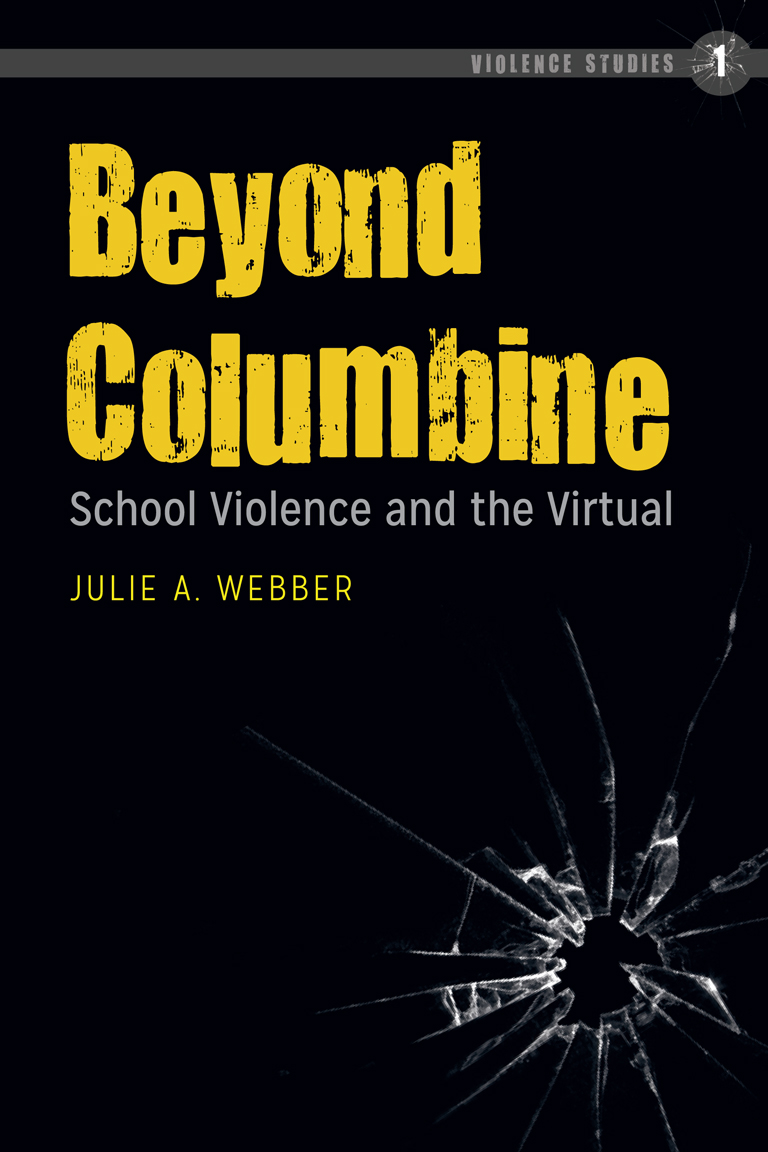

Julie A. Webber

Beyond Columbine

School Violence and the Virtual

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Webber, Julie A.

Beyond Columbine: school violence and the virtual / Julie A. Webber.

Pages cm. (Violence studies; vol. 1)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. School violenceUnited States. 2. ViolenceSocial aspects.

3. Violence in mass media. 4. Digital mediaSocial aspects.

5. War and societyUnited States. 6. United StatesMilitary policy. I. Title.

LB3013.3.W427 371.782dc23 2013020002

DOI 10.3726/978-1-4539-1176-1

ISBN 978-1-4331-2041-1 (hardcover: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4539-1176-1 (ebook pdf)

ISBN 978-1-4331-3836-2 (epub)

ISBN 978-1-4331-3837-9 (mobi)

ISSN 2161-2668

Bibliographic information published by Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek.

Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de/.

2017 Peter Lang Publishing, Inc., New York

29 Broadway, 18th floor, New York, NY 10006

www.peterlang.com

All rights reserved.

Reprint or reproduction, even partially, in all forms such as microfilm, xerography, microfiche, microcard, and offset strictly prohibited.

| About the author(s)/editor(s) |

Julie A. Webber is Professor of Politics and Government at Illinois State University. She has published several books and essays. Among them are Failure to Hold: The Politics of School Violence and The Cultural Set Up of Comedy: Affective Politics in the U.S. Post 9/11.

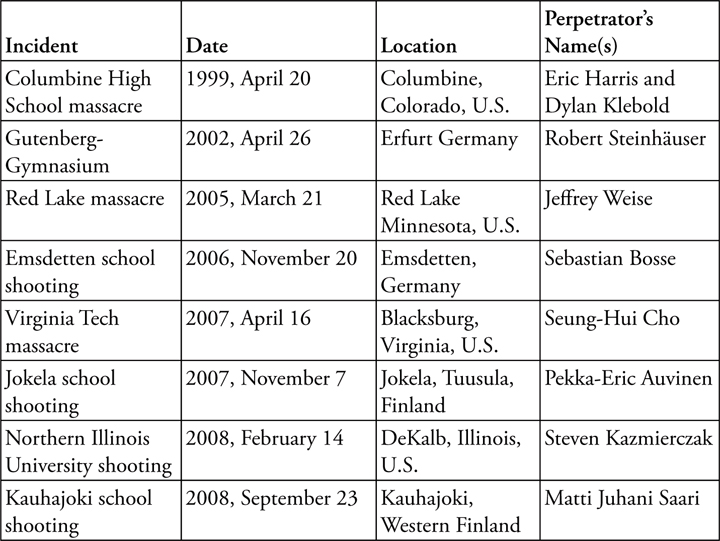

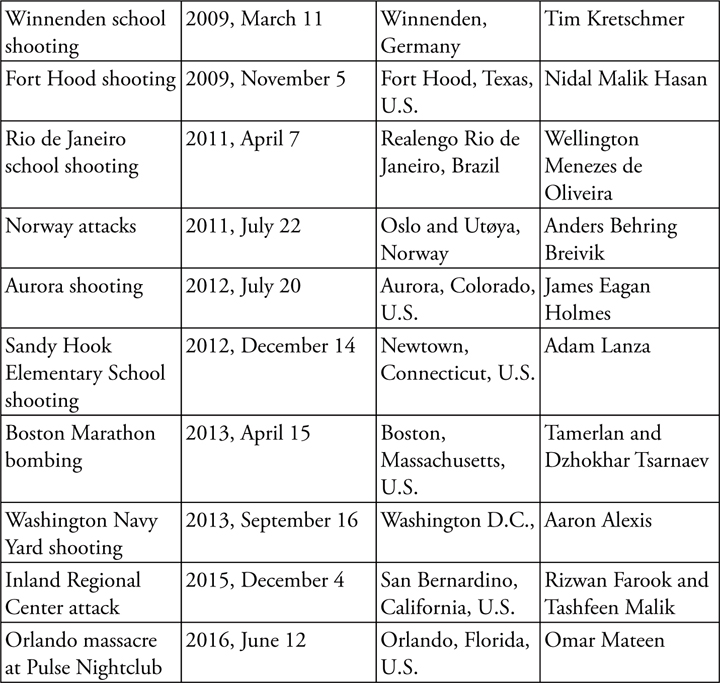

School violence has become our new American horror story, and it has its roots in the way it comments on western values with respect to violence, shame, mental illness, suicide, humanity, and the virtual. Beyond Columbine: School Violence and the Virtual offers a series of readings of school shooting episodes (Red Lake, MN, 2005; Virginia Tech, 2007; and Northern Illinois, 2008), as well as similar cases in Finland, Germany, and Norway, among others and their relatedness.

The book expands the authors central premise from her earlier book Failure to Hold, which explores the hidden curriculum of American culture that is rooted in perceived inequality and the shame, rage, and violence that it provokes. In doing so, it goes further to explore the United States outdated perceptual apparatus based on a reflective liberal ideology and presents a new argument about proprioception: the combined effect of a sustained lack of thought (non-cognitive) in action that is engendered by digital media and virtual culture. The present interpretation of the virtual is not limited to video games but encompasses the entire perceptual field of information sharing and media stylization (e.g., social networking, television, and branding). More specifically, American culture has immersed itself so thoroughly in a digital world that its violence and responses to violence lack reflection to the point where it confuses data with certainty. School-related violence is presented as a dramatic series of events with Columbine as its pilot episode.

This edition of the eBook can be cited. To enable this we have marked the start and end of a page. In cases where a word straddles a page break, the marker is placed inside the word at exactly the same position as in the physical book. This means that occasionally a word might be bifurcated by this marker.

| vii

This book has been a long time coming. Im glad its done. Thanks to my family and friends for support.

Added value was achieved by the brilliant suggestion of Marie Thorsten that we attend Timeline Theatres production of Harmless, a play about questionable creative writing at a small Midwestern university by a returning Iraq soldier. Thanks also goes out to Brett Neveu, the playwright, for making scripts to Harmless, as well as Eric LaRue, immediately available to me upon request.

Thanks to Jim Thomas for making time to reflect with me. Also, thanks to Tomi Kiilakoski and Atte Oksanen for their brilliant work on school violence in Finland. Nathalie Patons work on school violence and social media is invaluable.

I am motivated by reviews of my work and several reviewers of the first book on this theme, Failure to Hold: The Politics of School Violence, deserve mention since their careful criticism and their endorsement of certain themes in the book formed in my mind the great bulk of what the reader will find here. Thanks to Dennis Cooper for his selection of my book and use of the insight about equality as the drive to violence on his blog, where he examines school shootings in interesting detail. This project would not have been possible without the support of two summer university research grants provided by the Illinois State University. Organization, proofing and bibliographic work was completed with the assistance of an undergraduate research assistant, Steve Reising. Thanks also to Courtney vii | viii Johnson for assisting with preparing the manuscript for submission to my publisher, as well as critical discussion of the book with me.

Thanks to the provosts office staff at Illinois State University for helping me to locate demographic data on student attendance at universities.

Thanks to Ali Riaz, Marie Thorsten, Diane Rubenstein, and John Weaver for providing feedback on final drafts of the project.

Thanks to Felix Murchadha, for feedback and support.

This book is for my dad.

| ix

ix | x

| 1

Most rampage shootings are a form of retaliatory violence; they are revenge for perceived past wrongs. Columbine gave new meaning to school rampage shootings, especially to disaffected outcast students not only in the United States but throughout Western society. Rampage shootings were no longer the provenance of isolated, loner students who were psychologically deranged. Columbine raised rampage shootings in the public consciousness from mere revenge to a political act. Klebold and Harris were overtly political in their motivations to destroy their school (Larkin, 2007). In their own words, they wanted to kick-start a revolution among the dispossessed and despised students of the world (Gibbs & Roche, 1999). They understood that their pain and humiliation were shared by millions of others and conducted their assault in the name of a larger collectivity. Klebold and Harris identified the collectivityoutcast studentsfor which they were exacting revenge. That is what distinguishes Columbine from all previous rampage shootings (Larkin 2009, 132). 1 | 2