Stanford Studies in Middle Eastern and Islamic Societies and Cultures

SHOWPIECE CITY

HOW ARCHITECTURE MADE DUBAI

Todd Reisz

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Stanford, California

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Stanford, California

2021 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

All rights reserved.

This book has been published with the assistance of the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts, the Stimuleringsfonds Creatieve Industrie (The Netherlands), and the Netherlands Foundation for Visual Arts, Design and Architecture (FBKVB).

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Reisz, Todd, author.

Title: Showpiece city : how architecture made Dubai / Todd Reisz.

Other titles: Stanford studies in Middle Eastern and Islamic societies and cultures.

Description: Stanford, California : Stanford University Press, 2021. | Series: Stanford studies in Middle Eastern and Islamic societies and cultures | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020004569 (print) | LCCN 2020004570 (ebook) | ISBN 9781503609884 (cloth) | ISBN 9781503613867 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Harris, John R., 1919-2008. | ArchitectureUnited Arab EmiratesDubaiHistory20th century. | City planningUnited Arab EmiratesDubaiHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC NA1473.2.D83 R45 2020 (print) | LCC NA1473.2.D83 (ebook) | DDC 720.95357dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020004569

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020004570

Cover design: Kevin Barrett Kane

Cover image: Fastened to the building by wire, construction workers install the inner layer of the Dubai World Trade Centre towers double facade. Photograph taken from the construction cranes bucket, 1978. Photograph by Gordon Heald.

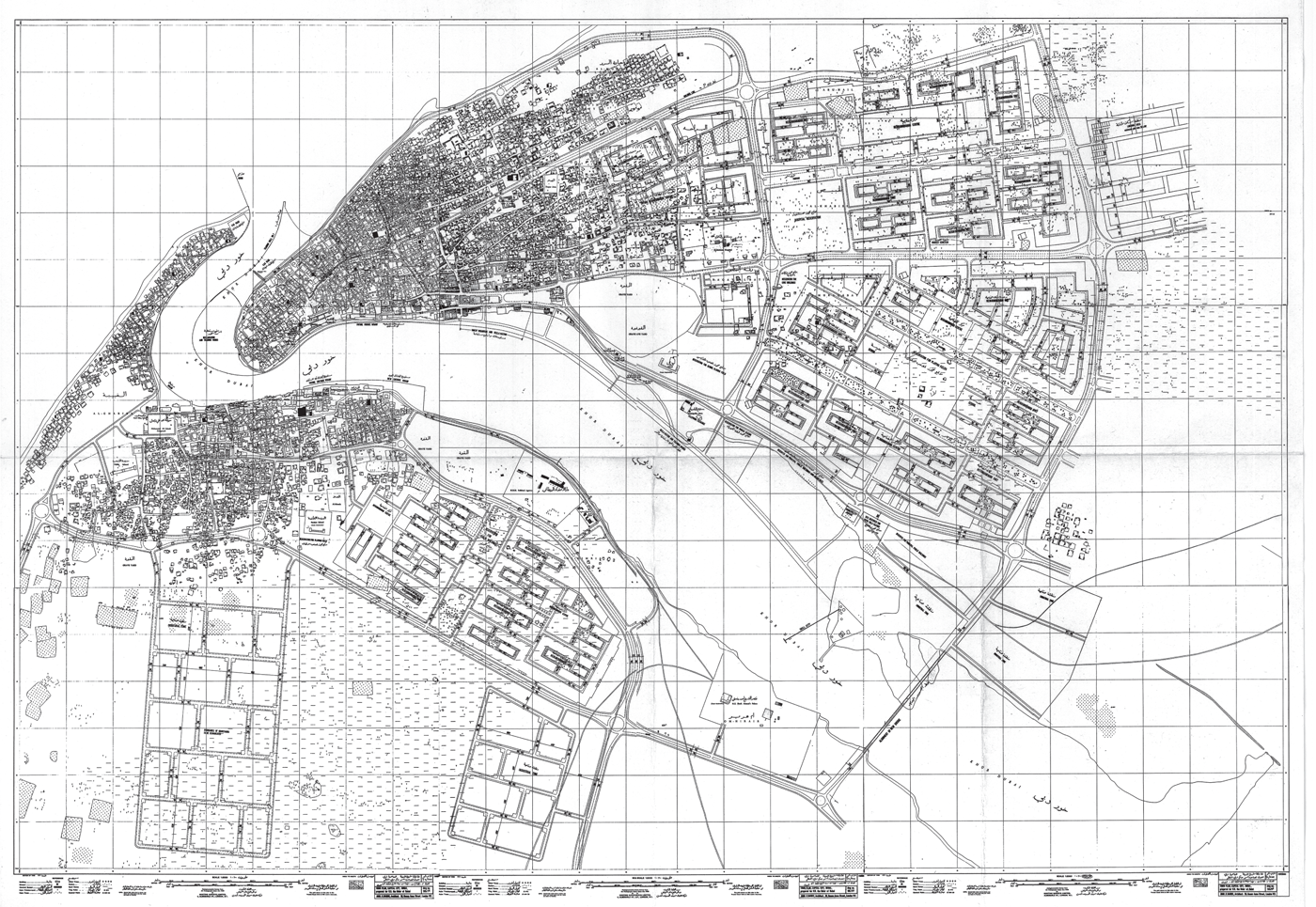

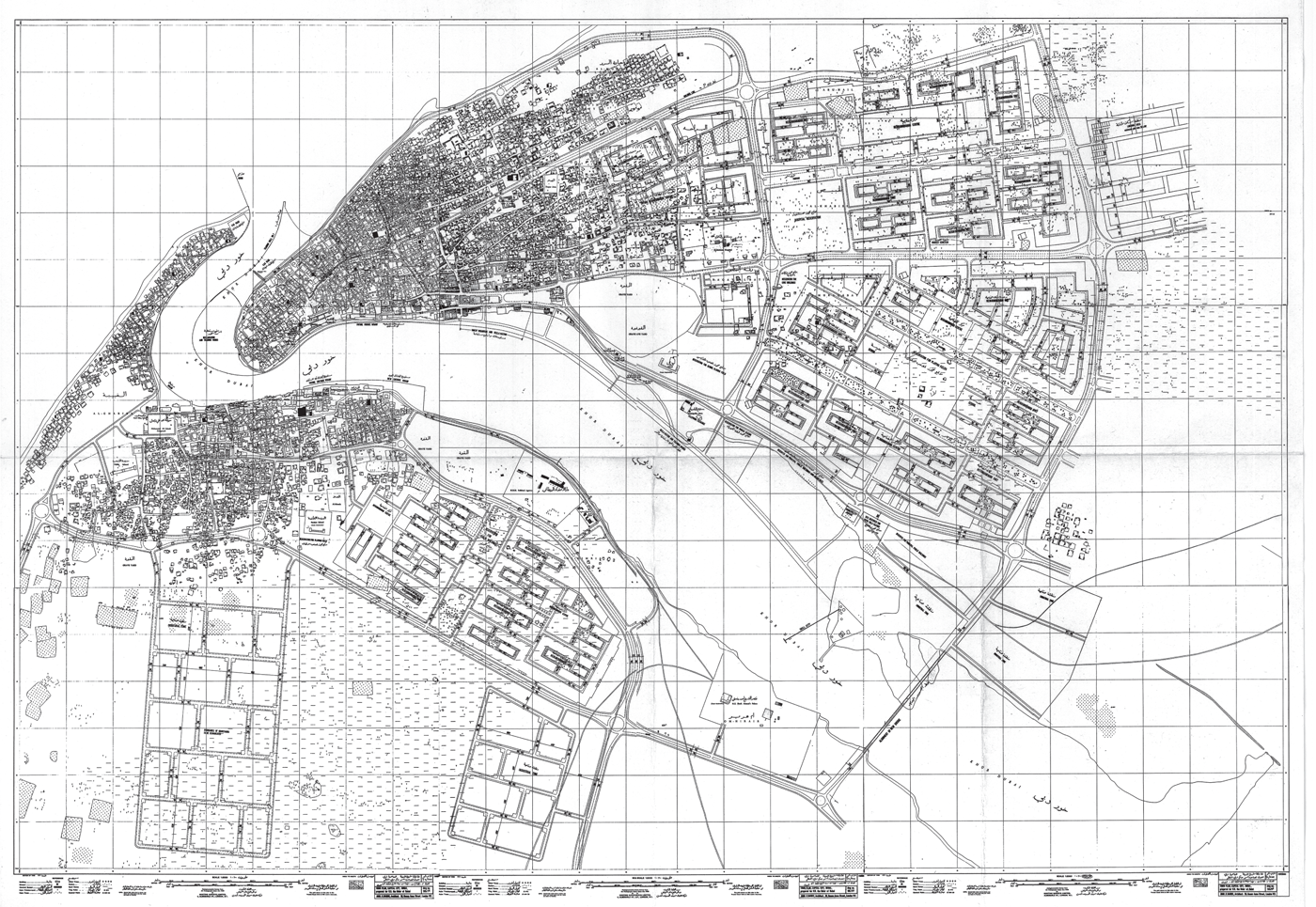

Map on pp vi and vii: The Dubai 1960 town plan. Courtesy John R. Harris Library

Text design: Kevin Barrett Kane

Typeset at Stanford University Press in 11/15 Brill

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

HERES A PLAN

MANY PROLOGUES have been written for Dubai. Some of these take place at the citys khor, or creek: the marshy waterway that Arabs, Iranians, and South Asians made into a harbor. Others start in Haifa, Khartoum, Kochin, and Saigon. There are as many prologues as starting points for journeys to Dubai. And they can be infinitely rescripted to fit the themes at hand and to anticipate those to come. No prologue is an origin. Each is an epilogue for stories before its own. Its where one chooses to begin, for now.

This prologue opens in London in 1959, because this is where many people licensed to change landscapes stood ready to change Dubais. It is toward the end of a summer of shimmering lawns and refreshing shade. Many recalled that summer being just warm enough that an iced drink sweat through a linen napkin. Benevolent sunlight merely added color and definition to gardens that appeared to care for themselves. Such manageable conditions can seem far away from a summer endured in Dubai, where the only reprieve from howling sands that can cut through skin and the hard, diamond-bright sun was the inside of an airless, aching souk.

The difference between the two worlds composed a common narrativethe first portrayed as pleasant and accommodating, the other as grueling and inadequate. The two settings were the stage for how ideas and modern things were dispatched from one world to improve the otherthings like electric grids, asphalt roads, hospital care, and hotel lobbies. Architects had no major role in this narrative, not yet, but they were ready couriers of expertise, with calculations and measurements to rectify any apparent deficiency. They were trained to chart delivery, and therefore to guarantee it. Architecture though offers more than the assembly of itemized ingredients. On a landscape that had endured millennia without it, the building of reinforced-concrete architecture would declare urgency, its completion would announce arrival, and its advertisement, as a showpiece, would affirm that standards had been set, and met, and that more was on the way.

Cold drink in hand, the British architect John Harris was at a garden party that summer in Londons plush and verdant neighborhood around Campden Hill Square. It was the right place at the right time. He had just turned forty and ran a small architectural practice. He had a reputation for courtesy and composure. Mindful of others and alert to where he stood in a room, he spoke in clipped, gentlemanly tones and could sense exactly which anecdotes and insights were going to convey his thoughts.

As disorienting as his last five years had been, the next three were productive and deliberate. Once he regained his health, he matriculated again at Londons Architectural Association and secured his degree in 1949. He met his wife, fellow architect Jill Rowe, during their studies. In 1949 they opened their one half of one room office in their Marylebone home, but Britains Harris wanted to translate the trauma of his imprisonment into designing for extreme climates. The couple pursued commissions far away from Britain, in places endowed with the petroleum required by the recovering British economy. In 1951, the firm was hired to design a small building research station in Kuwait, thanks to a family connection. In 1953, the pair won an open design competition for a new hospital in Doha, a city expanding on Qatars petroleum profits. They delivered the hospital four years later as the surrounding regions largest architectural project. Such an accomplishment should have led to an influx of clients. Instead, Harris learned that new work did not materialize on its own. That realization might have been on his mind at the garden party.

There, Harris met Donald Hawley, who at thirty-eight was Britains ranking official in Dubai. He was in London for holiday that he timed to escape Dubais most insufferable month. His position in Dubai was considered a hardship post. As the political agent for the Trucial States, Hawley embodied more than a century of British control over Dubais access to the outside world. The garden partys host, Hawleys and Harriss mutual contact, was also supplying experts: English-language teachers through the British Council for new planned schools. An architect or town planner was not on Hawleys contact list, but Harris had the skills to convince him that one should be.

As a rule, Hawley kept to telling simple stories. He was paid to portray the British intercession in Dubais affairs as fair and constructive. Hawley later claimed he organized Harriss initial visit to Dubai so that he would produce the citys first town plan. The story may be told as matter-of-fact: Two men mindful of their respective careers forge a gentlemens agreement to shape the future of a place 5,500 kilometers away. In actuality, Hawley was not authorized to hire Harris, much less to mastermind an outright modernization program for Dubai. Instead he was instructed to choreograph the appearance of change without the British, or any other foreign entity for that matter, seeming to dictate it.