Dorling - Inequality and the 1%

Here you can read online Dorling - Inequality and the 1% full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Lightning Source Inc, genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Inequality and the 1%: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Inequality and the 1%" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

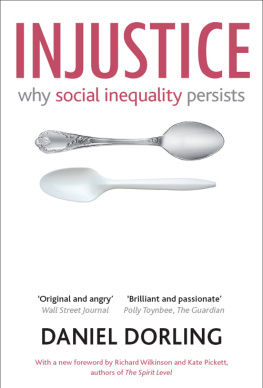

Dorling: author's other books

Who wrote Inequality and the 1%? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Inequality and the 1% — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Inequality and the 1%" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

and the 1%

Published by Verso with a new preface 2019

First published by Verso 2014

Danny Dorling 2014, 2015, 2019

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78873-647-3

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-586-0 (US EBK)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-994-3 (UK EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British library

The Library of Congress Has Cataloged the

Original Edition of this Book as Follows

Dorling, Daniel.

Inequality and the 1% / Danny Dorling. 1st Edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-78168-585-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-78168-586-0 (ebk)

1. EqualityGreat Britain. 2. PovertyGreat Britain. 3. Social classesGreat Britain. I. Title. II. Title:

Inequality and the one percent.

HM821.D6697 2014

305.50941dc23

2014017678

Typeset in Sabon by MJ & N Gavan, Truro, Cornwall

Printed in the UK by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

To Carl Lee who knows what matters most

It used to worry me, and I thought it wrong to have so many beautiful things when others had nothing. Now I realise that it is possible for the rich to sin by coveting the privileges of the poor. The poor have always been the favourites of God and his saints, but I believe that it is one of the special achievements of Grace to sanctify the whole of life, riches included. Wealth in pagan Rome was necessarily something cruel. Its not any more.

Lady Marchmain from Brideshead Revisited

The wealthy attempt to console themselves in many different ways. One route is religious, suggesting Gods favourites are the poor and that makes up for the injustices they experience. Some claim that their riches are merited by their immense imagined talents. Another tactic is to suggest that it has always been like this; although it is lamentable that many have so little while a few have so much, it is inevitable. Charity will have to suffice. None of these excuses is true.

The fictional Lady Marchmain was musing in the early 1920s, at the start of an era of immense social change and during the last period when economic inequalities in British society began to fall. It was that fall in inequality that brought drastic change to her life and to her familys. That fall was more important to her than anything else; more important than the First World War or the loss of the colonies. Try to imagine the shock of the rich in the 1920s and 1930s as they watched their wealth melt away before their eyes.

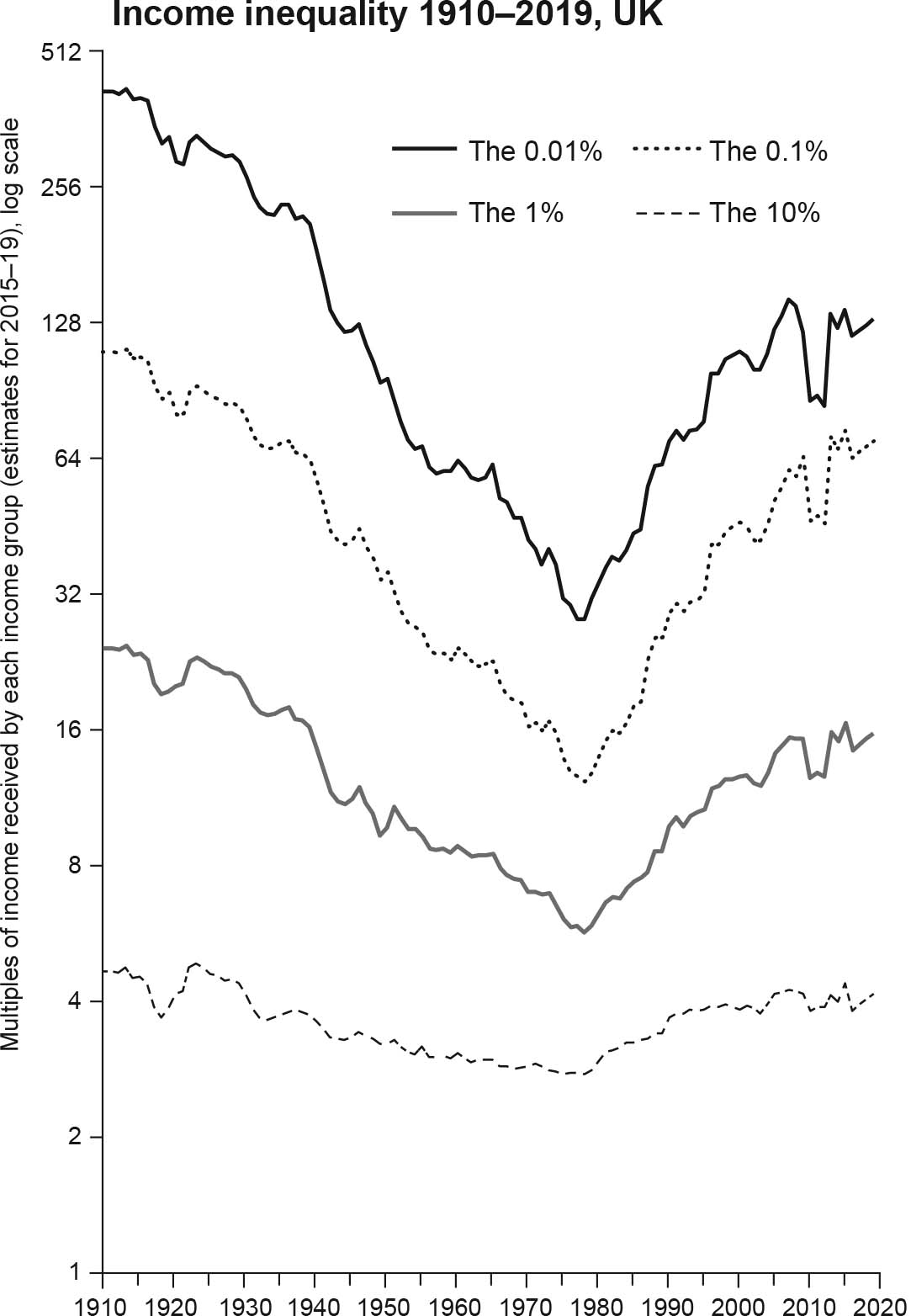

At the time when Lady Marchmain was reflecting on her divinely sanctioned wealth, the best-off tenth in society were taking almost 50 per cent of all the income in the country, leaving only half for the other 90 per cent of people in Britain; but that was beginning to be corrected, and in the late 1920s the level of inequality would fall more rapidly than ever before or since. In the early 1920s, within that top tenth of the population, the top 1 per cent were taking almost a quarter of the national income every year half of what the entire top tenth took. Within that top 1 per cent, the best-off tenth of a percent, in 1923, were taking 9.29 per cent of the national income, almost one hundred times the average income. And within that tiny portion was the group in which Lady Marchmain belonged, the highest earning fraction; the 0.01 (just 1 in 10,000 people) were taking 3.34 per cent, or 334 times as much as the average person.

Lady Marchmain may have been fictional, but she was based on the very real and extremely wealthy families of her day. She and they had never worked, or even imagined ever working. Her income was derived from investments, most of which would have been held overseas in the British Empire. She spent her days worrying about not saying the wrong thing in front of the servants, about her errant son Sebastian for whom all the riches of the world were no salvation, and about whether she would fit through the eye of the needle when her time came.

In 2015, when the second edition of this book was published, we knew not only that we were back to the late 1920s but also that income inequalities were still rising. Average income on the graph below equates with the value of one on the vertical axis. Any group taking above the average income results in many others getting less than one. By 2014, the best-off tenth of adults aged twenty and over in the UK were taking four times the average income. As a result, the remaining 90 per cent of people were getting by on only 0.67 of the average income.

Sources: Pre-tax national income share including pension income, individuals over age 20, from Dorling, Fairness and the Changing Fortunes of People in Britain, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society; Atkinson, Hasell, Morelli and Roser, The Chartbook of Economic Inequality; M. Brewer, What Do We Know and What Should We Do about Inequality?; and 20152019 extrapolated from household data given in Shine and Webber, Using Tax Data to Better Capture Top Earners in Household Income Inequality Statistics.

In 2014 the best-off 1 per cent took fifteen times the average income, a share almost identical to what they took before the Second World War. The best-off 0.1 per cent scored a multiple of sixty-seven, a share so high that they had last achieved such excesses only in 1936 other than in 2013, when their take was 7.2 per cent of the national total, or seventy-two times average earnings and that year the best-off 0.01 per cent took 130 times average earnings. It is sobering to realise that 130 times is three times less than in Lady Marchmains day, although 130 times the average was what the share of families like hers had been reduced to by 1943. The fictional lady died (appropriately) in 1926, the year of the general strike.

It is all too easy to forget the past, and we have to look a long way back to see a situation as bad as the one we are facing today. If we are very optimistic, then it is possible to believe that income inequality recently peaked in the UK. By several measures our quality of life in Britain peaked much earlier, in 1976, which far from coincidently was when income equality peaked. This compares to one in five of all adults being so insecure, 3 per cent of whom often go without food. Between 2004 and 2016 food insecurity among the least well-off almost doubled.

As more and more people go hungry in Britain, as homelessness rises and overall life expectancy begins to fall, we see wealth inequality still rising. Wealth inequality tends to lag behind the trend of income inequality. On 12 April 2019 Mike Brewer of the University of Essex revealed the most recent income inequality data. All eyes quickly turned to the very last data point, and the up-tick from 2015 to then. Income inequality briefly fell during and immediately after the financial crash of 2008. Now it appears to be rising again. However, there are many reasons to believe that we may be at a peak.

As Mike Brewer explained, There is a big difference in what tax data says about the very rich and what household surveys say. Tax data reveals that the very rich continued to drift upwards until 2008. The financial crisis took a chunk out of top incomes, but by 201516 they were clearly on a rising trend.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Inequality and the 1%»

Look at similar books to Inequality and the 1%. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Inequality and the 1% and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.